Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

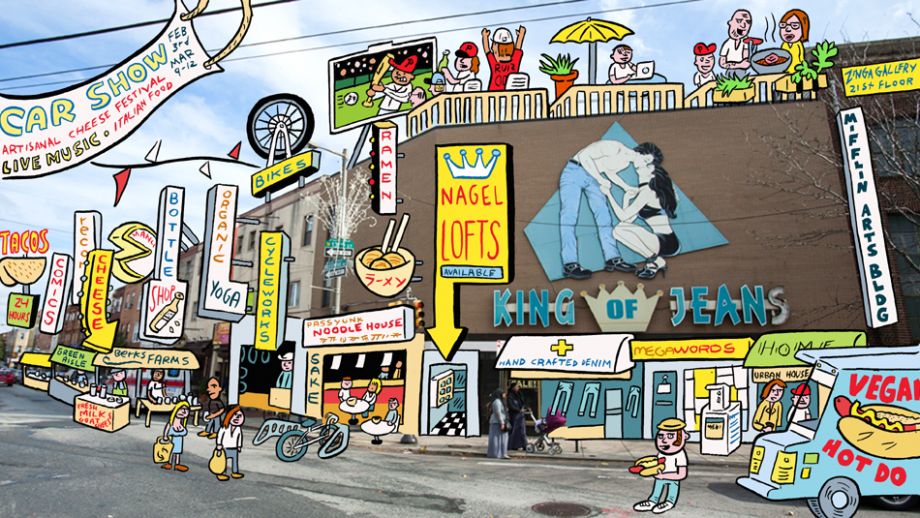

Become A MemberAlong Ridge Avenue, in the Francisville neighborhood of Philadelphia, single rowhomes, their adjoining neighbors long since turned to rubble, stand like orphans in a sea of vacant lots. Ridge was once a bustling shopping district, with innumerable small retailers, restaurants and theaters, but you wouldn’t know it now. Most of the shops are gone, many of the buildings that housed them are gone, and many of those that remain are vacant or have been converted into residences.

For older, dense cities like Philadelphia, few images convey the plight of urban decay more than derelict commercial avenues. Block after block of once-prosperous main streets has been reduced to abandonment and marginal trades. Yet these places still often function as gateways, greeting visitors to urban America and creating indelible impressions of an area’s health and viability.

Even after a generation defined by the growth and revitalization of urban centers, many such historic shopping avenues still struggle to survive against competition in the suburbs and, increasingly, online. But while the mall defined late 20th-century consumption, there is compelling evidence that the 21st will bring a return to the urban main street as city neighborhoods across the country surge back to life.

But while meteoric regeneration can be glimpsed on commercial corridors like Cherokee Street in St. Louis or Frenchman Street in New Orleans, many other strips continue to sit underused. In the case of Ridge Avenue, surrounding residential blocks are prospering from the neighborhood’s proximity to downtown Philadelphia, even while the shopping corridor itself languishes. To find the elusive formula that makes the difference for places like Francisville, cities have spent millions hiring consultants and undertaking multiyear plans of action. Some have worked. Many others have not.

At Next City, we believe that no single formula for revitalization exists. Instead, every corridor requires its own specific, place-based strategy. That said, there are tools out there that can be useful for developing the strategy that will work in your community.

In that spirit, Next City has profiled four Philadelphia corridors that have rebounded using tools that we think are worthy of attention. All four of these corridors — 13th Street in Center City, Passyunk Avenue in South Philadelphia, Lancaster Avenue in West Philly and Frankford Avenue in Kensington — offer compelling evidence of the potential for rebirth on streets that, a generation ago, were left for dead. Here we lay out the challenges these corridors face, their reinvention process and, finally, the innovative fixes they’ve used.

The Problem: Although long the epicenter of Philadelphia’s gay community and adjacent to many wealthy downtown neighborhoods, 13th Street has been known since the 1950s as one of Center City’s most prominent red light districts, and certainly the most enduring. While legendary gay bars like Woody’s and countercultural institutions like Robin’s Bookstore found a home in the rugged strip of ornate 19th-century buildings, many city residents long regarded the area as a den of vice crime.

It was on 13th Street that big city boss Frank Rizzo got his “tough on crime” reputation, arresting bookies and petty gangsters as a district commander in 1952. It was just off of 13th Street that the then little known writer-turned-cab driver Mumia Abu-Jamal was arrested for the murder of police officer Daniel Faulkner in 1981.

The association with crime led to the decline of numerous large, historic commercial buildings along 13th Street, creating a major obstacle to redevelopment in an otherwise burgeoning section of the city.

The Process: Like many downtown cores, Philadelphia has a business improvement district (BID), known as Center City District. What that means is that property owners in the district pay a tax surcharge so the BID can provide services for the downtown above and beyond what the municipality offers. For decades, the organization provided extra street cleaning, security, lighting and infrastructure with the theory that eventually businesses would take notice of the nice streetscape and begin to make investments of their own. In 1998, the investment began to prove itself on 13th Street.

That year, Tony Goldman, known for reviving Miami’s now famous South Beach neighborhood, started scouting storefronts and tough-sell office buildings on the strip. Attracted to the faded elegance of the street, the developer gradually acquired clusters of buildings along the downtown strip in order to slowly introduce new small businesses, deliberately selecting quirky tenants that fit his vision for what the corridor could become. Inserting a restaurant essentially created by Goldman Properties as an early anchor, the company then sought out well-known local entrepreneurs as tenants, eventually landing Philadelphia restaurateur Steven Starr’s flagship gourmet Mexican restaurant El Vez on a prominent corner.

“We always embrace the local entrepreneurial community and the creative class,” said Craig Grossman, managing director of Goldman Properties. “We went looking for the tastemakers, locals that had what we thought were smart business plans.”

Some early picks were Val Safran and Marcie Turney, who opened the BYOB Lolita in a Goldman building nine years ago. Since then, the duo has forged a small empire in the area, opening two additional restaurants, a boutique chocolate maker and an upscale grocery store.

In the ultimate testimony to the district’s turnaround, an abandoned strip club last year became Nest, a boutique, café and indoor playground where children can take classes while parents enjoy a latte or browse high-end toys. “We used to describe it as the ‘hole in the doughnut,’” said Grossman, “but not anymore.”

The Fix: Tax Increment Financing

It’s tempting to believe it took only a few brave entrepreneurs and the market to reinvent 13th Street, but the reality is far more complex. Goldman and tenants like Turney and Safran would probably never have had the success they did without the combination of taxpayer-funded street improvements from the Center City BID and support from the city government itself. The support was channeled through a financing mechanism known as tax increment financing (TIF).

TIF programs, originally pitched to Goldman by historic preservationists concerned with the deterioration of 13th Street’s buildings, are incentives that allow developers to reinvest tax revenue increases back into a site. While popular among developers, TIFs generate controversy because they divert money from government coffers to create closed loops, wherein money generated by the private sector stays in private circulation.

On 13th Street, the TIF means that buildings owned by Goldman Properties pay a fixed amount of property tax while increases in their tax assessments from rising property values get transferred to a fund to pay for additional improvements. In a roundabout way, the TIF acts like a kind of tax credit for renovating 13th Street’s crumbling buildings. But unlike a tax credit, a TIF has a kind of “insurance” in that it only pays out if a developer’s work actually improves the surrounding area, thereby raising property values.

Though not without problems, TIFs have become popular around the country as investment-hungry cities seek to rehabilitate hard-to-finance buildings. Walking down today’s vibrant 13th Street, it’s not hard to see why.

The Problem: Passyunk Avenue was a quintessential Philadelphia shopping district in a quintessential South Philly rowhome neighborhood, long the epicenter of the city’s Italian community. As the surrounding working-class blocks started to gentrify in the 1980s, the area stayed true to its roots, with the strip dominated by family-owned trattorias, delis and clothing shops. These institutions carved out an improbable existence in the modern economy, catering to multigenerational households and former residents who returned from the suburbs to shop in the old neighborhood.

For decades, these older businesses hung on, but the strip started to exude, well, oldness. For years, Passyunk remained in a kind of weary stasis, missing out on potential customers and would-be entrepreneurs as newer residents from the blocks around the strip turned downtown for services and nightlife options.

A bustling street filled with butchers, tailors and cheese shops in the 1960s had become, by the 1990s, a non-destination with an ever-dwindling crowd of old-timers holding out amid a tide of increasingly marginal retail uses and residential conversions. The situation was bad for both old and new residents as the shopping area started verging into irrelevance.

The Process: As decline on Passyunk became more tangible, a local development group known as the Citizens’ Alliance for Better Neighborhoods was formed to fend off an all-out collapse. The organization bought property and did street cleaning, keeping the avenue from falling into the sort of seemingly hopeless disrepair seen on nearby corridors. But ultimately, and regrettably, it became apparent that the group’s higher purpose was less about improving Passyunk than lining the pockets of well-connected neighborhood cronies. Behind its charitable façade the organization was secretly operating as a slush fund for former state Sen. Vince Fumo.

In the wake of a scandal that saw Fumo’s arrest, the Citizen’s Alliance was dissolved and reformed as the Passyunk Avenue Revitalization Corporation. And the arrest, though traumatic for the close-knit South Philly community, became in the end a powerful catalyst for change.

With the organization in shambles, the state ordered Paul Levy, founding president of Center City District, to handpick a new director for PARC. The new guy — Sam Sherman, a local developer and Congress for the New Urbanism member — had a big job ahead of him. The previous board of directors had raided the group’s funds to pay for legal fees related to Fumo’s illegal activities, totaling in excess of $10 million. A court order prohibited the group from accepting any government money for five years. It was a scenario that could have spelled doom for many established economic development agencies, let alone Sherman’s nascent organization.

But Sherman used the restrictions as an incentive to streamline PARC, now staffed only by himself and a secretary. After generating $5.5 million in start-up dollars by selling off “superfluous” real estate assets, including a former charter school, he devised a strategy to get his organization back in the black.

“I was given the charge to evaluate the real estate holdings the organization had — and has — and refocus the organization on the core mission, which was [revitalizing] this neighborhood and the commercial corridor,” said Sherman.

How did he do that? By becoming a landlord.

The Fix: The Non-Profit Landlord

Soon after taking charge of PARC, Sherman began acquiring blighted commercial properties, essentially becoming Passyunk Avenue’s biggest single landlord.

It was a strategy partially fueled out of financial desperation created by the court restrictions on taking government money. But in the end, it has proven more powerful a tool than even Sherman imagined it would. PARC’s large commercial portfolio, which includes several properties acquired before the scandal, has allowed the group to handpick tenants and influence development in a way that matches its vision for the corridor.

By next February, PARC will control 15 high-profile commercial storefronts out of nearly 100 along Passyunk’s dense core. By offering affordable rental prices for unusual — but perhaps not especially lucrative — retailers, the corporation has raised the avenue’s profile as an eclectic shopping destination. Passyunk now sports a comic book shop, a scooter dealership and a few boutiques in PARC-owned storefronts. Another store sells handmade cycling apparel.

“I personally interview people that want to locate on the avenue,” Sherman said. “As opposed to having 18 Italian restaurants serving the same thing, or five cheesesteak places, we want to keep the avenue diverse, from a retail and restaurant standpoint.”

By converting previously empty upper floors of commercial properties into apartment units, the agency will soon be able to generate enough of a cash flow from its rentals to actually break even. Profitable apartments also have the reciprocal effect of enlarging the consumer base for the adjacent businesses below and add to the sense of Passyunk being active around the clock.

Sherman said creative entrepreneurs had begun to find Passyunk even before PARC entered the game. He views his role as making it easier for these businesses to thrive by making the avenue as a whole more interesting and active. “It’s not about squeezing people for the most money,” he said. “It’s trying to get the best business in there.”

It’s a strategy that has paid off as entrepreneurs have noticed the heat generated by the successful businesses PARC helped get in place. While Sherman’s group has yet another restaurant in the works, both a boutique home furnishing store and artisanal limoncello distiller are also slated to move into privately owned storefronts in the coming months.

The Problem: Lancaster Avenue is a major artery that runs across the northern half of West Philadelphia. Lined with unique rowhome-based commercial buildings, the street is eminently walkable, replete with a trolley line that directly connects with the city’s subway system. Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania’s Presbyterian Hospital anchor its eastern end, which features a small stretch of student-oriented shops. More westerly blocks are home to a heavily trafficked, albeit lower-income, neighborhood shopping strip.

Despite its considerable assets, Lancaster Avenue is a commercial corridor divided against itself. Many surrounding residential blocks grapple with poverty and vacancy, while the student population is largely clustered around the university and hesitant to travel too far up the avenue. There is sense of division between the eastern and western shopping areas, with a no man’s land of vacant storefronts in between. Both struggle, on one side because of the transient nature of student customers, and the other because of the limited buying power afforded by poorer residents.

The Process: Since its founding by a church pastor in 1972, the People’s Emergency Center (PEC) has been trying to bridge that gap. Initially meant to educate Drexel and Penn students about the reality of poverty in West Philadelphia, over the last decade the agency has increasingly branched out into economic development. It now has a team focused specifically on a six-block stretch of Lancaster Avenue.

But while the avenue was fortunate enough to have a university and hospital as stable pillars within the community, for decades these institutions all too often regarded their neighbors with a “hands-off” policy. It’s an attitude that’s seriously changed in recent decades with realization that — surprise! — good employees and good students are more likely to be attracted to jobs and schools in good neighborhoods.

These days, Drexel contributes to University City District, which has helped attract more retail to the area. The UCD functions similarly to Center City District, providing security patrols and improved lighting to a larger area with educational institutions picking up the tab. But Drexel, under new president John Fry, has recently expanded its presence on Lancaster. Through a relationship with PEC, it has brought investors to the street and lent student interns to help organize and promote regular art events, like Second Friday (a riff on the monthly citywide art festival, First Friday).

“It’s basically me and a co-op student at Drexel that really do the logistics behind the scenes, filling businesses with actual activities [on Second Fridays],” said PEC’s James Wright, adding that the event has helped draw students and residents up the avenue. The Emergency Center has helped place groups from Drexel at vacant storefronts for temporary art and technology events.

Drexel has also introduced a homeownership program for its staff, offering mortgage assistance to employees that buy homes in the surrounding neighborhood.

“They’re finally getting on the ball with promoting the neighborhood not just with students, but also with professors and alumni through homeownership,” said Kevin Musselman, also of PEC.

The upshot for economic development agencies, like the People’s Emergency Center, is a potential source of capital and consumers to ignite an underperforming commercial corridor. Its partnership with the university is an example of a still-nascent pairing of an economic development agency and a major institutional player. Early strides have been promising.

The Fix: A Community Anchor

In the midst of Lancaster’s dead zone that has kept the two poles of the avenue apart lies a blighted mental health facility. It housed businesses in a past life, but for decades the three-story rowhome was essentially used as a boarding house. The Emergency Center recognized that the facility was not being operated well and moved to acquire the building, which was in need of renovations.

What started as an opportunity for PEC to develop a new commercial space became an incubator for a dining concept advocated by a Drexel professor who had sought to address the issue of Philadelphia’s “food deserts.” Wright describes it as a “pay-as-you-wish” café that’s designed to bring low-cost, healthy food to the community.

“The model is to make a healthier breakfast or lunch,” said Wright. “If you have $2 to pay for this meal, you pay $2. If you have $8, that’s what you pay. It’s a way of addressing the quality of food that people have access to at a reasonable price, so people can pay what they can afford.”

The university will help underwrite the cost of discounted meals. Ingredients will be sourced through the West Philadelphia Food Hub, an organization that helps farms distribute fresh produce in the neighborhood. Ideally the project will appeal to both financially strained students and low-income residents.

Still in the planning stages is a concept for the building’s upper floors. Musselman envisions these levels occupied with “timebank” units, housing targeted at artists where residents trade off rental costs for community service “hours.” Timebank residents will meet regularly with community members to bounce around ideas for how to work off the hours, ideally using their creative skills to beautify their new neighborhood.

Although the timebank units are being built outside of their partnership with Drexel, they are the nucleus of a philosophy that seeks to bind two disparate segments of the community together.

The Problem: Frankford Avenue is the tattered boundary between two neighborhoods: The stable, working-class Fishtown and Kensington, a much larger, more heavily industrialized area, famous in the 19th century for its mills. Frankford fed and clothed legions of workers and housed businessmen that came into a nearby train depot, all of which are long gone.

While Fishtown was able to keep some measure of normalcy, Kensington did not fare well during its inevitable deindustrialization. As the two neighborhoods went down different paths, Frankford Avenue became like a DMZ, claimed by no one. For decades, the street was relegated to an existence as an essentially superfluous commercial strip, its buildings crumbling away to nothing. Once the gateway to Philadelphia’s northeastern neighborhoods, the avenue was pushed further into obsolescence by the mid-century construction of Interstate 95.

By the early 2000s, much of southern extent of Frankford, once a solid, curving line of commercial rowhomes, had rotted into blocks of gap-toothed wastelands.

The Process: Frankford Avenue has faced some of the most extreme challenges possible for an urban commercial zone. Solutions are difficult when there is little left to build off of besides the few remaining residents. But for the past decade, that’s exactly what the New Kensington Community Development Corporation has had luck doing. (Full disclosure: I worked at the NKCDC between 2008 and 2010.)

The NKCDC began organizing the Kensington Kinetic Sculpture Derby, a “race” that features mobile Goldbergian contraptions designed by local artists. While forging community bonds from the loose collection of artisans that had scratched out a living in Kensington, the event also helped popularize the area with attendees as a cool, artistic center. Selling it as a funky nexus for the cutting-edge was certainly aided by the fact that residential development had skyrocketed in neighborhoods to the south, making them too expensive for most artists.

“The Sculpture Derby has been a wild success,” said Henry Pyatt, commercial corridor manager at the NKCDC. “You get 10,000 or 12,000 in the neighborhood, and our surveying shows that about half those people are from outside the neighborhood and even the city. It’s exactly what we need, just giving people the idea that this is a decent neighborhood, destigmatizing this place.”

Residential construction has boomed in Fishtown and Kensington, and the area has become legitimately hip in spite, or possibly because of, its desolation. However, although Frankford Avenue has reached the point where most intact commercial structures are now occupied, it has struggled to make the development of new commercial space a reality.

Many vacant expanses of land are actually numerous smaller lots, with internecine ownership. It’s a serious challenge for the commercial corridor, what with French restaurants and artisanal pizza places feeling exposed amid the empty space. It’s another area the CDC has tried to manage creatively, lacking the funds to develop so many abandoned parcels.

“We physically maintain a lot of them,” said Pyatt, referring to NKCDC’s grounds keeping team, which cuts grass and cleans lots whether the corporation owns them or not. “But we also have a vacant property list, so when folks come into the office with a business idea, I can show them parcels they could purchase.”

Pyatt said his group wants to have a voice in the future development of the land, and has used their limited resources to buy “keystone” lots, securing one lot in the middle of several to use as leverage in encouraging appropriate development when the time comes.

Although his group has managed to execute major streetscape improvements, many future plans are still speculative (as is so often the case in severely depressed commercial avenues). But the remoteness and isolation that for so long harried the area may also be its strength, as the CDC experiments with ideas that would be unthinkable in many neighborhoods.

The Fix: Self-Determination

In a neighborhood with few resources and no institutional anchor, there is a strange freedom that comes from having to work from the bottom up. These are places where the failure of the government and private market are most apparent, and have the greatest need for economic development. But resources are usually scarce, and all that remains are the residents, their talents and their imagination.

The city designated Frankford an “arts corridor” in 2004, leading the NKCDC to create a redevelopment plan that centered on promoting the neighborhood’s human capital. The designation primarily existed as a vision.

“There wasn’t even a coffee shop or a gallery on the corridor at the time,” said Sandy Salzman, executive director of New Kensington, explaining that the key became making Frankford a place to showcase the artistic talent in the neighborhood.

Outreach was a big component to engaging the incoming artistic class in the broader goal of economic development.

“Some [artists] were already starting to move into the neighborhood, as they were getting priced out of Old City and Northern Liberties, but they were not making themselves known,” Salzman said. “We had a meeting with all of the local artists in order to educate them about buying property, particularly on the corridor, so they wouldn’t be forced out again and they would be more visible.”

On the corridor, NKCDC rehabbed a commercial building, enticing a small theater company to locate in a small black box space, with the troupe organizers living above. The group also financed the renovation of a café, so that people actually had a place to meet and connect with other artists and residents.

The CDC worked hard to bolster those resources by enticing more artists to come to the area. Channeling affordable housing dollars, the group was able to rehab a former textile mill into a 27-unit artist community, featuring workshops and exhibitions on the ground floor. Part of the aforementioned streetscape improvements centered on recruiting local metalworkers to construct unusual bike racks and signage, employing locals with infrastructure dollars.

The investments have paid off as the area’s art scene has become famous locally.

“On the last First Friday, we had hundreds and hundreds of people out on the avenue,” Salzman said. “It was just amazing.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

_200_200_80_c1.jpg)

Ryan Briggs is an investigative reporter based in Philadelphia. He has contributed to the Philadelphia Inquirer, WHYY, the Philadelphia City Paper, Philadelphia Magazine and Hidden City.

Hawk Krall is an illustrator, cartoonist and former line cook known for food paintings that have appeared in magazines, restaurants and hot dog stands all over the world. In Philadelphia, he is known for his “factually creative” drawings and paintings of the city’s neighborhoods, most recently exhibited at Space 1026.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine