Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberHere is a short list of things people would like to see in the South Side of Chicago’s Pullman neighborhood: a railroad film festival; a Trader Joe’s; some sort of hospitality-industry training facilities; the perpetual rebuilding of a late-19th-century sleeper car; bike-share stations; public bathrooms; weekend brunch.

The list of what’s there already is much shorter: a new Walmart and a new fitness center; some historical sites; a diner that becomes a bar in the evening; and a McDonald’s — all in 300 acres that span 12 blocks from north to south, and about a half mile east to west. Pullman was once an ambitious model company town, elegantly designed down to its last detail. Today, it struggles with the same problems that urban neighborhoods everywhere face: poverty, segregation and crime.

Pullman is searching for a 21st-century identity, and what that will be is now a topic of critical debate in Chicago. The neighborhood is too historic and too valuable to let languish. Its history is too important to be repackaged into another look-alike warehouse district.

In January, the grandest reinvention of all was introduced before the U.S. Congress. The idea: designate Pullman as a national historical park, under the administration of the National Park Service.

A Pullman National Historical Park would be a bit of a departure for the park service. Pullman, after all, is a residential area where Chicagoans vastly outnumber monuments and unlike other Park Service sites in cities — think Independence National Park in Philadelphia’s Old City or the New Orleans Jazz park just outside the French Quarter — the area has never been a major tourist draw. The proposal is now in the hands of legislators — at any point, the body can, with the approval of the president, declare the site a national park. In May, Pullman advocates returned to Capitol Hill to lobby for their new designation.

“Pullman has an inspiring story to tell,” U.S. Rep. Robin Kelly said in a press release when the bill, which she co-sponsored in the House, was introduced. “It’s the story of a great industrialist and hard-working laborers who together built a product that revolutionized railroad travel and helped to develop a strong working class. As we move forward into the Digital Age, it would be fitting for Congress to honor America’s Industrial Age by creating a Pullman National Park.”

Pullman park, with its explicit economic development focus, could be highly influential in a part of the country rich in struggling urban neighborhoods and desperate for federal support to revitalize them.

Mark Bouman, a geographer at Chicago’s Field Museum, is a vocal supporter of the park plan. He says a national park in Pullman would help make the case for investing in other nearby historic industrial sites, pointing to the redevelopment of Germany’s Ruhr region, an area similar in scale to the Calumet industrial region that includes Pullman. Essen, a former mining community in the heart of the Ruhr, was named a European Capital of Culture in 2010. The designation — similar in symbolic terms to being named a U.S. National Park Service entity — helped the post-industrial German city draw people and investments to the region and reinvent itself in a way that was true to its history.

“People are likely to come visit Pullman at a faster pace than they do now,” Bouman says, “and then they’re gonna say, ‘Okay, what else?’”

Walk through the Pullman and the first thing you notice will likely be the tree-lined streets of brick row houses on the neighborhood’s south side, all designed by a single 19th-century architect, Solon Spencer Beman. Pullman is one of the oldest model company towns in the U.S. and remains largely intact, with 1,000 residential units designed in the American Queen Anne style. The houses are small, but in recent years have become more valuable.

“It’s still the kind of neighborhood where you can walk around and, at dusk, when the light’s just right, really get a sense that you’ve stepped back in time,” says Arthur Pearson, who purchased his home in 1996. Drawn by South Pullman’s quiet livability and small-town feel, Pearson — a onetime professional actor who now runs arts and environmental programs for a local foundation — bought a fixer-upper. It’s now an immaculate site, larger than it was with the addition of a back sun porch. Pearson says.

It wasn’t just the neighborhood’s look that attracted Pearson. He knew about Pullman from his grandfather, who emigrated from Sweden in 1888 for opportunities to work at factories in the area. He found work at the Pullman Palace Car Company, first as a day laborer in the lumberyard, and eventually as an inside finisher, working on the interiors of the famous luxury railcars the company produced. He lived in company housing in the north part of the town. Arthur Pearson grew up in the suburbs south of Chicago, but found himself quickly at home in his grandfather’s old haunts.

“If I live here three more years it’ll be known as my house as opposed to the previous owner’s,” he jokes.

Pearson lives on the right side of the tracks in the former railcar town. A short walk from his home in South Pullman, construction crews are slowly renovating two striking 19th-century structures — the Pullman company’s administration and factory buildings and the opulent Hotel Florence. The grand edifices, topped by a clock tower and gabled rooflines, are constant reminders of the wealth once generated in the neighborhood. Meanwhile, a walk in the other direction, through the neighborhood’s north side, is a reminder of the decades that came later. There, neglected houses languish and crime persists on unwatched streets. In 2012, the median household income in southern Pullman was nearly twice that of northern Pullman, census data shows.

It’s that troubled geography that Pearson and other advocates for the park want to fix. Chicago doesn’t need another neighborhood riven by gentrification and class divides, especially not on blocks that were once home to a powerful working-class population.

The park “is not about just a house tour. It’s a vehicle,” says Lyn Hughes, who founded the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum in 1995, one year before Pearson moved to Pullman. “It’s a tool that can be strategically and skillfully used to bring economic development to this community using what the community has to offer: culture.”

Social experimentation is nothing new to Pullman. When George Pullman built his factory, he designed an entire town around it. Workers would rent homes owned by Pullman. Their lawns would be attended to, as would their health, education and recreation. In creating this hermetic and heavily paternalistic village, Pullman was responding to the widespread labor unrest of the 1870s — he meant his effort to improve the moral stamina of the working classes.

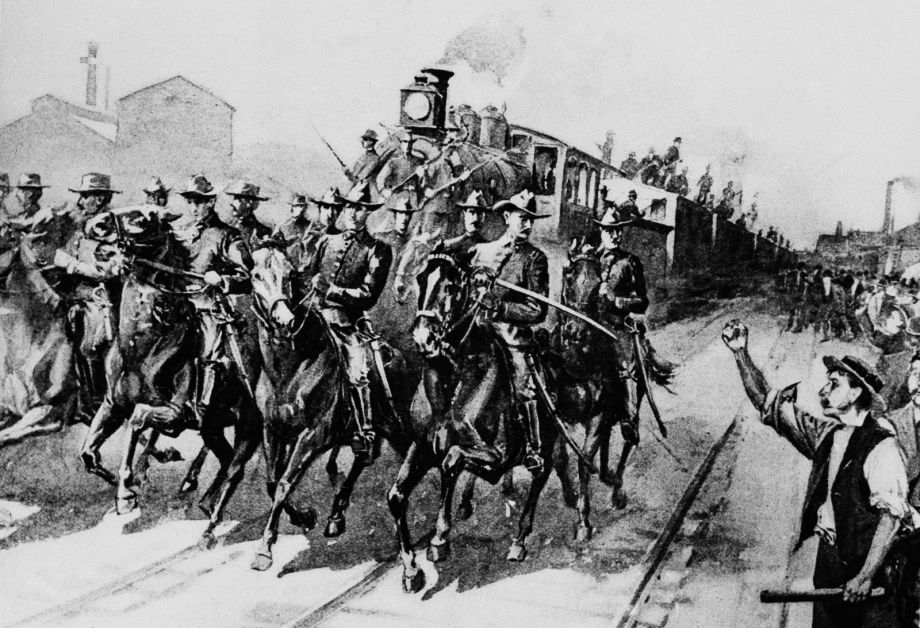

By 1893, a financial panic led to layoffs and wage cuts at the Pullman factory, without a corresponding reduction in rents. Workers resisted, and in 1894, a countrywide series of strikes spread to the company. While George Pullman abstained from negotiation, the American Railway Union’s 125,000 members threw in their lot with the Pullman workers, refusing to touch Pullman cars; rail traffic was tied up from Chicago to the West Coast. The strike was eventually broken, but so was the spirit of the company town. After an 1898 Illinois Supreme Court decision found the Pullman corporation in violation of its charter, all nonindustrial property was put up for sale.

Federal troops escort a train through jeering, fist-shaking workmen in Chicago in this drawing of an incident during the Pullman strike of 1894. (AP)

There was also a racial component to the company’s history. For the job of porter, George Pullman hired African-American men exclusively (often former slaves). The choice had profound, if unintended, consequences. In the 1920s, the Pullman company was the largest private employer of African-Americans in the country, and even as other companies began to increasingly hire blacks, Pullman remained one of the larger corporate contributors to the black middle class until the company dissolved in 1968. The company and its trains also played a role in the civil rights movement; porters distributed copies of black newspapers like the Chicago Defender as they passed south. But even as the porters spread the words of that movement, they suffered degrading treatment at the hands of Pullman’s white owners. In 1925, the treatment led the porters to create the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, the first black union chartered by the American Federation of Labor, which successfully negotiated a contract with the Pullman company in the mid 1930s. The union was led by A. Philip Randolph, who later went on to head the 1963 March on Washington. It also helped launch the career of E.D. Nixon, a onetime porter who was instrumental to the Montgomery bus boycott. The union’s history is preserved locally at Hughes’ A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, which sits within the boundaries of the proposed park.

It’s a wild idea, turning a living, breathing city neighborhood into a national park. But unusual as it may sound, designating Pullman as a national park run by the same agency that controls such rural treasures as the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone won’t mean importing exotic plants or even slowing down the pace of residential development. Supporters say the designation will simply help Pullman get the resources it needs to keep growing in the decidedly urban fashion it always has.

The former U.S. Rep. Jesse Jackson, Jr. was the first loud advocate of the park in 2012 when he requested a study of the suitability of a National Park Service designation. Jackson said the neighborhood could become “the Grand Canyon of the South Side.” He imagined the two main Pullman buildings, the central Greenstone Church and a decaying market square, and surrounding homes as draws for tourists and locals interested in Chicago’s history.

Backers imagine that only a small portion of Pullman — perhaps just the administration complex on the southern side of the neighborhood — would come under NPS ownership. Other public buildings might stay in the hands of the institutions that already own them, like the State of Illinois, and private residences would remain as they are. The area would be a lived-in, walked-through historical attraction. A park designation, explains Natalie Franz, a park service planner who coauthored a recent study on Pullman, “doesn’t give us permission to walk all over somebody’s lawn. It gives us the ability to work inside [park boundaries] in a way we wouldn’t otherwise.” Residents are hopeful that the sort of interest that attaches to a site with the National Park Service brand will inspire development of some of the more quotidian amenities that the neighborhood sorely lacks, like restaurants, grocers and other retail outlets.

The Pullman Factory is the architectural heartbeat of the neighborhood surrounding it. (AP Photo/Seth Perlman)

And Pearson has numbers on his side. An analysis commissioned by the non-profit National Parks Conservation Association, which is organizing the push for the park, estimates that the designation could, within five to 10 years, mean a six-fold increase in tourism, boosting the tourist headcount from 50,000 a year up to 300,000. After 10 years of park operations, the association estimates that Pullman could generate $40 million in annual economic output.

But even getting to the point of having an operational park could take as long as 10 years. If approved by Congress and President Obama, a National Park Service designation itself simply commits the federal agency to work with locals to develop the site. There are no specifics beyond that — no particular prescriptions or regulations and likely, a very modest budget. The National Parks Conservation Association anticipates the park would run with two or three full-time staffers and an initial operating budget of $350,000. “The old legacy parks of Yellowstone and the Tetons — those are capital-intensive babies,” says Mike Wagenbach, the superintendent of the Pullman State Historic Site. “The feds just don’t do that so quickly anymore.”

Social experimentation is nothing new to Pullman.

The proposal for a national park in Lowell came from Patrick Mogan, the superintendent of Lowell’s schools from 1977 to 1982, who pointed out that students were learning from books what they might learn experientially: the history of American manufacturing. About 30 miles from Boston and incorporated in 1829, Lowell was an early textile center that relied on hydropower from adjoining waterways. By the mid-20th century, technological advances and the migration of the textile industry to the American South had rendered the factories obsolete. The last of the large mills closed in 1958, leaving behind five million square feet of empty space and a depressed urban area, which by 1976 had the highest unemployment rate of any Massachusetts city. “In 1978, when the national park was created, you could stand anywhere in this downtown, turn 360 degrees, and see nothing but blight,” says Peter Aucella, the deputy superintendent of Lowell National Historical Park. One architect suggested replacing the mills with parking lots. Aucella recalls the national park officials balking at the idea of taking a role in the declining city before eventually being won over.

The hard-won legislation that created Lowell National Historical Park established two separate entities: a national park inhabiting its traditional role as a sort of institutional tour guide, and the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission, which would collaborate with the city on preservation efforts and find development money for the adaptive reuse of the empty mill space.

Lowell’s progress has largely tracked with early preservation plans made for it. A recent state report found that an initial $64 million federal investment in Lowell, funneled through the park service and the Lowell Historic Preservation Commission, leveraged another $65 million in public investment and $440 million in private investment over the park’s 30-year life. Aucella says that by 1999, 46 percent of Lowell’s 5.2 million square feet of mill space had been redeveloped. When some ongoing projects finally conclude in the next few years, 94 percent of the mill space will be in use, he says.The National Park Service has in the meantime changed its tune on urban parks. “Back in the ‘70s, when this was being conceptualized, national parks did what they did — which is to say, you acquire a place that’s of some significance, you renovate it, you provide maintenance to it, you provide tours and public access, you provide security, and that’s it,” says Aucella. But Lowell National Historical Park was conceived to address the specific problem of urban disinvestment, and that meant a different approach. Today, the National Park Service counts a handful of urban parks under its umbrella, running the spectrum from historic sites like Philly’s Independence Park, home to the Liberty Bell and the hall where the Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution were signed, to simple nature preserves to far less traditional spaces.

The most recent urban park to be designated by Congress is Great Falls National Historical Park in Paterson, New Jersey, approved in 2011. Three years later, it’s open to the public for a walking tour, but little new growth has occurred. The final draft of the park’s general management plan will be made available for public comment this summer. “It’s interesting to see this growth from the ground up — you see how slow it is, and how undefined it is,” says Zach Honoroff, a former director of programs for the Hamilton Partnership for Paterson, a non-profit group formed to assist NPS in planning the park.

Part of the impediment to growth is the difficulty of measuring the economic impact of urban parks. In regular reports on visitor spending effects, the National Park Service studies how its parks affect the economic activity in “gateway areas”: the 60-mile radius around park boundaries. The most recent found that in 2012, visitors spent $14.7 billion in gateway areas, supporting 243,000 jobs. In urban areas, though, there is often more than one park within the 60-mile zone, not to mention numerous other draws. Which gets credit for the spending? Without that quantifiable evidence of value, gathering support for park designation can be difficult. Still, analysis of specific sites shows healthy benefits — in Lowell, for instance, or in San Antonio Missions National Historical Park where a 2011 analysis found the Park Service’s $4.8 million operating budget in 2009 leveraged an additional $3.4 million in local investment, and generated almost $100 million in economic activity.

The Paterson park highlights another early industrial city, but other NPS parks are essentially nature areas that run through urban centers, like Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, a 72-mile stretch located in and around Minneapolis and St. Paul. Still others are smaller historic venues, like William Howard Taft National Historic Site in Cincinnati.

And a notable few engage more deeply — sometimes more contentiously — with their urban setting. The Presidio of San Francisco, for instance, is administered under a model unique to national parks: Decisions about it are made by a trust (the NPS retains an advisory role), and the park is entirely financially self-sustaining, relying on revenues from leasing its many on-site properties. (The park was a former Army post.) The arrangement has led to fierce battles over what is and is not appropriate in a national park. “There are positive elements” about the Presidio example, says Neal Desai, the Pacific region associate director for the National Parks Conservation Association, “and some of the biggest headaches that we’ve seen in the Bay Area come out of that area.” In an ongoing fracas, the Presidio Trust is struggling to figure out what to do with one local site, Crissy Field, after recently rejecting a slate of ideas it had solicited in a competition — including a museum proposed by the filmmaker George Lucas since recast for Chicago —and electing to start anew.

Chicago is rich in shuttered historic buildings and desperate for federal support to revitalize them.

Across San Francisco Bay, in Richmond, California, Rosie the Riveter National Historical Park looks more like the vision for Pullman. The park is really a collection of historic buildings, under the ownership of various entities, all stamped with the NPS brand. It was conceived in the 1990s as a modest public art project to recognize women’s contributions to the Richmond shipyards during World War II and has grown slowly. It only opened its visitors’ center in 2012 — 12 years after the site was designated. “We sort of went in this with rose-colored glasses, thinking that after two or three years we’d have our park full-blown and operational,” says Tom Butt, a local architect and 19-year member of the Richmond City Council. “It’s really taken over a decade to get there. But you’ve got to start somewhere.”

The Ford Assembly Building, pictured in 2000, is part of the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historic Park. (AP Photo/Ben Margot)

So how well does the Lowell example apply to Pullman? Lowell represents what Pullman envisions for itself: the creative adaptation of a former urban industrial area. But differences between the two communities make any comparison tough. “Lowell is similar in that it has a lot of similar themes of industry and community,” says Natalie Franz, the NPS planner. But, she adds, “Lowell is a bigger presence in a smaller city, whereas Pullman is a smaller presence in a bigger city. So there may be some challenges of scale there.” There’s also the matter of money — Pullman’s initial investment is expected to be much, much smaller than Lowell’s $64 million.

Working in the park plan’s favor is the fact that there is no organized opposition to it. Instead, there is cautious support with caveats mostly related to fears of gentrification. Tom Shepherd, a Pullman resident and one of those cautious supporters offers a list of questions that won’t be addressed for a long time. “I don’t want to say I’m skeptical, but I’m just unsure of the benefits,” Shepherd says. “Me, as a resident — what is it going to do for me? More traffic? More people to wave to and say hi to? That’s all very nice, but economic benefit — I’m a renter now — is my home value going to go up? Are people going to get priced out of their homes?”

David Listokin, the Rutgers professor, coauthored a 1998 paper that noted, amid broader findings of salutary economic benefits, a risk of residential displacement in historical districts undergoing revitalization — a risk that can be mitigated, the study noted, by meaningful community participation in the process. I asked Listokin, a supporter of the Pullman proposal, to put himself in the position of a resident. What would he be worried about? Parking? Property taxes? He suggested that the modest scale of whatever happens in Pullman will soften its impact on the neighborhood. “I only see good economic things happening from this,” Listokin says. “It’s not like they’re taking a huge swath of taxpaying land and converting it into a non-profit-type use. So what’s the downside of it? You’ll have people working and people visiting who are spending.”

The firm PlaceEconomics studies the economic impact of historic preservation for public and private groups. While the group has found that preservation efforts often drive job creation and other significant economic impacts, its principal Donovan Rypkema says that in historic neighborhoods, the first concern should be livability. “A strategy of economic revitalization and community health and vibrancy,” writes Rypkema in an email, “will have to be comprehensive and address such things as proximity to: transportation, neighborhood business districts, schools, community facilities, parks, etc.” He cites what he calls a “truism”: “If you do it for the locals, the tourists will come; if you do it for the tourists, only the tourists will come.”

In Pullman, this was a concern recently for Mark Konkol, a journalist who lives in the area. He wrote last year of his anxieties about the ongoing renovations of the Hotel Florence: “If the $3.5 million in renovation fails to do more than shore up an old building for the sake of ‘historic preservation’ then let me be the first to say that my neighborhood — a special piece of Chicago history desperately in need of restaurants, retail shops, coffeehouses or decent taverns — got a raw deal.”

The stately red-brick administration building and factory George Pullman built in 1880 remains today the center of the neighborhood, with or without park designation. Damaged by fire in 1998 and only partially restored, the administration building is nonetheless an impressive feature of Chicago’s South Side. Its broad campus, recognizable by its clock tower, hosts neighbors who tend gardens, keep bees and play Frisbee golf. It’s open occasionally for events, but without with an operating budget, there are no regular hours, and most parts of the complex are cut off from public access.

In late March, I met Tom Shepherd outside a diner on 115th Street, Pullman’s southern boundary. Shepherd lived here in the early 1970s and returned in 1999 following his wife’s death. He looked across the street at a parking lot attached to the Sherwin-Williams paint factory. When he first lived here, Shepherd recalled, the whole lot was devoted to production. “There were lots of jobs in steel, chemical, the paint factory. Pullman-Standard was still making railcars… It was a highly industrial area. Everybody was working. You could quit one place and walk next door and get rehired, there were so many jobs available at that time.”

When the regional economy tanked, Mike Shymanski, an architect and now the president of the Historic Pullman Foundation, was in the middle of redeveloping the Pullman Wheelworks building. A block-spanning, L-shaped factory structure in the north part of the neighborhood, Wheelworks isn’t vintage Pullman, but was built in 1903 to manufacture Packard automobiles. Shymanski’s residential adaptation included a health club and a space for parties. But by the time the 210-unit development came online, “the Calumet area started to hemorrhage jobs,” Shymanski says. “When we started it, things were very positive economically around here. But by the time we got it to the actual occupancy part, that’s when things really went downhill.” What was supposed to have been a mixed-income development became exclusively Section 8.

The developer’s story hints at the challenges that Pullman will face as it builds a new identity as a park district.

“There’s just been more neglect” on the northern end, says David Doig, the president of Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives, a non-profit community development group working in the area. “There’s been more absentee owners, and now with the foreclosure problems, it has been exacerbated.”

Yet there are positive signs of progress too. In 2012, Wheelworks was renovated again and given a makeover touted as a strong example of historic preservation. Happily for Section 8 tenants, the rent remained the same with none of the displacement that often comes with renovations. In the surrounding blocks, Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives has rehabbed and sold about 30 vacant houses in the last several years and also engineered a new business complex just outside of the historic district. Walmart moved to Pullman Park last year as the complex’s first major tenant. Doig says the National Park Service designation would complement the economic development already under way in Pullman.

Sales for rowhouses in north Pullman, Doig says, have been “much more robust” this year, since the Walmart opened and talk of the park became formalized in congressional legislation. The park, he says, could be a “unifying opportunity so we don’t have to talk about north Pullman and south Pullman. We can talk about Pullman.”

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine