Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

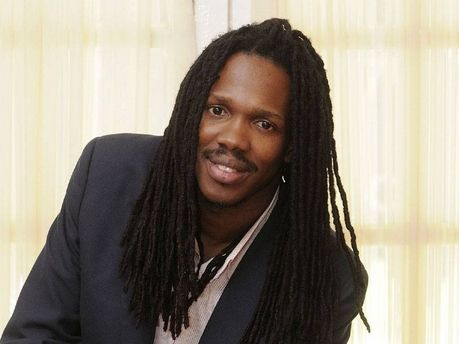

Protoje (center) performs with his band The Indiggnation. (Photo by Yannick Reid)

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberI heard the low rumble of bass even before I passed through the gate. Descending dark stone steps cradled by tropical vegetation, I rounded a corner and the source of the music came into view: an imposing stack of amplifiers, four speakers wide and twice my height. This was no hodgepodge collection of audio equipment, but a fine-tuned, custom-built sound system.

On a Sunday night in November, the tower of speakers, named Rockers Sound Station, was playing reggae and dub music for the weekly music session known as Dub Club. Perched high above Kingston in the residential Jack’s Hill neighborhood, Dub Club takes place on an expansive hillside veranda overlooking the city’s twinkling lights below.

The club was packed with a mix of locals warming up before heading out to other parties, diehard reggae and dub fans, white expats from the embassy crowd and foreign music tourists like myself who paid the JMD$500 ($4 U.S.) cover charge to smoke a spliff and marinate in the music. The sound system stood sentry at one end of a concrete courtyard where off to the side, the owner and operator of Rockers Sound Station, Gabre Selassie, commanded the scene with turntables, a mixer and a microphone.

“Music that’s bold to rock up your body and soul,” Selassie rhymed on the mic before dropping the needle on a vintage 12-inch vinyl record. The sound of dub washed over the crowd until around 2 a.m., when the night ended peacefully and the fans filed out to negotiate with taxi drivers for the ride downhill.

Uneventful endings to such parties are no longer a guarantee in Kingston. Today Jamaica’s world-famous music culture, a main driver of the city’s economy, is under threat due to heavy-handed enforcement of a 1997 law called the Noise Abatement Act. The legislation allows the police to shut down amplified sound events in response to anonymous noise complaints.

In Kingston, amplified sound is a near constant, from car stereos to loud storefronts to parties known as street dances that blast more contemporary forms of Jamaican music like dancehall. But those parties, popular among lower-income Jamaicans and a dedicated cadre of foreign fans, are facing increasing scrutiny, in part because of their proximity to residential neighborhoods in a city that doesn’t strictly zone such activities.

A rendering of one of Kingston's proposed entertainment zones. (Credit: Dorraine Duncan and Jhordan Channer)

In April last year, the police showed up around 11 p.m. and asked to see a permit for Dub Club. Forty-seven-year-old Selassie, born Carlisle Lee, showed one from the municipal government, but the cops demanded to see one from the police department, too. Lee had applied for the police permit but hadn’t yet picked it up. When the police told him he would have to leave mid-party and go with them to the station, he refused. Tempers escalated, and the police tasered Lee and fired tear gas into the crowd.

Lee was arrested but the charges were later dropped when the police determined he did have a permit. While street dances are regularly halted without garnering much official response, the Dub Club dust-up was an embarrassment for authorities seeking to cultivate a positive image of a city with a crime-ridden reputation, as the Sunday night session has international renown among white foreign tourists and is endorsed by the Jamaica Tourist Board.

Olivia “Babsy” Grange, minister of culture, gender, entertainment and sport, spoke out against the arrest. Ultimately, she believes the relationship between the police and music community needs to improve.

“His work has grown out of a desire to promote our culture and he should be praised for that,” she told the Jamaica Star. “The support his event gets from Jamaicans who love roots culture, tourists who come to Dub Club each Sunday night, as well as those who follow it online each week, underscores how world famous our culture is.”

While a 20-year-old law continues to stifle music events, a group of advocates from academia, politics and the music scene are pushing for a solution: dedicated entertainment zones in which amplified sound, the lifeblood of Kingston culture, isn’t subject to shutdowns by the police. They hope Kingston’s recent designation as a UNESCO City of Music will push the current central government administration to finally amend the Noise Abatement Act. While the proposed zones don’t sit well with everyone in a music culture often suspicious of authority, they may be the only hope to keep the music playing in the birthplace of sound system culture.

Jamaica is the only country on the planet to have invented eight genres of music in the second half of the 20th century. That’s according to Sonjah Stanley Niaah, a cultural studies professor at the University of the West Indies who directs the Reggae Studies Program. She rattles off the eight genres with pride: mento, ska, rocksteady, reggae, dancehall, dub, nyabinghi and EDM. (The latter requires an asterisk: Niaah argues that Jamaican producers’ pioneering studio techniques in the 1970s laid the groundwork for how today’s EDM producers make chart-topping hits, and superstars like Skrillex and Diplo openly acknowledge a debt of gratitude to Jamaican musical innovation and incorporate Jamaican vocal samples into their work.)

Sonjah N. Stanley Niaah speaks at a conference.

The country’s cultural impact may be immeasurable, but Jamaican music’s economic contributions are both quantifiable and impressive. According to Niaah, Jamaica’s annual music exports are worth nearly $100 million, or over 8 percent of the country’s total exports. Based on permits issued between 2012 and 2016, the economic impact of the Jamaican entertainment sector is estimated at over JMD$71 billion ($56.7 million U.S.) annually.

Kingston has always been the hub of this economic sector. An estimated 6,000 people work in the music industry, the vast majority of them in Kingston. Niaah described the city as a “crucible” where musical creativity from the countryside — like Bob Marley, who was born in rural St. Ann parish — converges on the capital. “This city cannot survive without these creative impulses,” she said.

That statement rings true after a week immersed in Kingston’s music scene, where dancehall reigns supreme and both reggae and dub are enjoying a resurgence after years of having fallen out of favor among local music fans. I witnessed the exuberant dancehall moves that get copied by Justin Bieber and Drake, the rising reggae crooners breathing new life into the genre that made Bob Marley one of the most popular musicians on the planet and the sound system yards strewn with spare speaker parts that cobble together some of the world’s most powerful audio rigs.

“The sound system is our national instrument,” Niaah argued. She cited a 1974 report to the prime minister by Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson who recommended that every village in the country have its own sound system.

But not everyone is as optimistic that Jamaica’s government believes music is crucial to the country’s future. Damion Crawford was the minister of entertainment and tourism from 2012 to 2016. It was the first time the government’s entertainment portfolio was placed in an economic rather than a social ministry, which Crawford hoped would boost a major export industry for a small country with limited industrial resources. Right off the bat, though, he had to fight for a budget to fund entertainment industry projects.

“That is because entertainment is seen as recreation, and dancehall is seen as idling,” he told me, lamenting how attending music events during his time in government was viewed as frivolous while education and health ministers received praise for visiting schools and clinics. “That divide is because dancehall came from bottom-up and government came from top-down.”

As a result, Niaah believes the impact of Jamaica’s musical contribution to the world is “something our leaders have not fully grappled with.” Instead, they fear it. The signing of the Noise Abatement Act coincided with the growing popularity of dancehall, a kind of digital reggae with a faster tempo and harder rhythms than the soothing sounds of dub. Samples of gunshots and airhorns pepper dancehall tracks, as do lyrics about narco-trafficking, violence and frank sexuality. (They also have a reputation for homophobia, though that is slowly improving.)

Like gangster rap in the U.S., dancehall’s brash subject matter does not sit well with some more conservative parts of society even though it fuels a huge local culture with a global influence. It has produced popular stars like Sean Paul, Buju Banton and Bounty Killer, but has also landed others in hot water — the reigning king of the dancehall, Vybz Kartel, is serving a life sentence for murder in a Jamaican prison.

By the act’s signature in 1997, dancehall events, which just as often take place in the street as in enclosed venues, were also taking place in more affluent Uptown. In a city with a stark divide between low-income downtown neighborhoods and rich uptown enclaves, that shift brought the late-night sound of dancehall through the windows of the business, professional and political classes, who responded with the law.

The legislation was enforced with renewed vigor after the 2010 arrest of drug lord Christopher “Dudus” Coke. The most popular street dance, Passa Passa, which spawned copycats around the Caribbean and its diaspora, was held in Coke’s stronghold of Tivoli Gardens. Following his capture by the Jamaica Defence Forces and extradition to the U.S. with the help of the Drug Enforcement Agency, the police initiated the current wave of crackdowns.

Increased enforcement seems at odds with other priorities. In 2008, the central government declared February as Reggae Month in a bid to boost local awareness and encourage music tourism. “[Visitors] expect to see a city thumping with music,” Niaah said. “It’s ironic the only type of regulation we’ve had seeks to ban [music] versus having productive conversations about Kingston as a creative economy going forward.”

Ultimately for Niaah, the very terminology of the law is a reflection of a colonial-era attitude that does not valorize indigenous culture. “‘Noise abatement’ needs to shift in terms of a philosophical framework from the articulation of noise to the articulation of sound,” she explained. “We have not given the world noise, we have given the world sound.”

In 2013, while Jamaica was gearing up to nominate the Blue and John Crow Mountains as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, government officials like Crawford uncovered another UNESCO program: the Creative Cities Network. Started in 2004, the initiative seeks to unite cities from across the globe through creative industries. Cities can apply to become designated in one of seven creative fields, including music. In 2015, Kingston successfully bid to become a UNESCO City of Music, one of a handful of Global South entries joining the likes of Varanasi, India; Salvador, Brazil; and Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

UNESCO’s program, which launched two years after the publication of Richard Florida’s Rise of the Creative Class, takes its cues directly from that book’s philosophy: that creative industries are the driver of 21st-century urban economies, but that plenty of cities are not harnessing the potential of their creative sectors. By placing cities into networks based on their creative industry strength, UNESCO hopes to help cities meet United Nations sustainability ambitions enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda.

While many cities see the UNESCO designation as a marketing opportunity or a chance to raise the flag for a less-than-obvious attribute — who knew Paducah, Kentucky, was the quilt capital of the world, or that Seattle is a City of Literature, despite its large tech scene? — the opportunity in Kingston was to use an international stamp of approval to persuade the powers that be that music is important to Kingston’s prosperity.

Damion Crawford was Jamaica's minister of entertainment and tourism until 2016.

The government changed hands in February 2016 and so far, the new administration appears to be taking Kingston’s City of Music designation seriously. In November, Niaah, along with colleagues from the University of the West Indies and the Institute of Jamaica, organized a three-day conference, Imagine Kingston, to focus dialogue on Kingston as a Creative City of Music.

Gillian Wilkinson-McDaniel is a senior official at the Ministry of Culture, Gender, Entertainment and Sport. (The ministerial portfolio shifted slightly when the new government came in.) “It resonates well with Government House when you say, ‘look, Kingston has been designated a creative City of Music by UNESCO and so we plan to do these things,’” she told the crowd of 50-odd architects, planners, music scholars, business leaders, government officials (including the mayor), curators and artists who gathered at the University of the West Indies campus. The UNESCO designation, she said, “gives you a gravitas.”

As part of the application, the municipal and national governments agreed to pursue four concrete initiatives over the next two years, when the City of Music appellation comes up for renewal. They will renovate downtown’s historic but dilapidated Ward Theatre, establish a walk of fame in a public space, create a “reggae loop” connecting historic sites related to the genre and designate entertainment zones.

The last component is Crawford’s pet project, which he believes is the key to solving the Noise Abatement Act’s dilemmas. He envisions four categories for the city: a 24-hour zone where music is permitted non-stop; places where last call is at 4 a.m. instead of the current 2 a.m.; so-called “community zones” where a neighborhood petition signed by 60 percent of the residents can designate a certain time and day of the week when music is allowed; and one-off zones for communities that might celebrate a special event once a year.

The community zone system in particular is designed to provide a legal avenue to preserve the tradition of street dances, which Crawford said represented two-thirds of entertainment events that sought government permits in 2014. Even relatively tame street dances, like the city’s longest-running sound system event, the Rae Town Oldies Dance, have fallen victim to the Noise Abatement Act, with complaints sending the dance out of its namesake neighborhood to an empty lot next to the national cricket stadium.

Before he left office, Crawford’s team declared the 24-hour zone in an empty stretch of land near the airport called the Palisadoes, though it has yet to become a hotspot in the city’s dancehall geography. They also got as far as sound testing nine different surface parking lots downtown and suggesting six as good candidates for late-night music without bothering neighbors, but the zones were not officially declared before the election last year.

Almost two years into the new administration, there appears to be minimal progress toward implementation of the zone proposal. “Work on the demarcation of zones and associated regulations began but were interrupted by the change in administration,” said Grange, the culture and entertainment minister. “I now have this opportunity to complete the job and I am working hard to ensure that the zones and regulations are developed and implemented by the relevant authorities.”

Niaah, who continues to sit on the entertainment advisory board, is nevertheless hopeful. “There is potential to have downtown be a driver of entertainment events,” she said. “That’s where they started so it’s quite logical to move historically and futuristically into that endeavor.”

In the meantime, the music community is eager to see something done to improve the state of brick-and-mortar music facilities. At Imagine Kingston, the curator of the Jamaica Music Museum lamented that his permanent collection has no permanent home. Music scholars decried the death of the vibrant record store culture on downtown’s Orange Street, once a vinyl lover’s pilgrimage site known as “beat street,” where in an ironic twist, funeral parlors are now the main business. The new generation of Jamaican musicians is more likely to distribute music digitally but they still need somewhere to play. Protoje, known for his steely-eyed realism in songs like “Kingston Be Wise” and “Blood Money,” is a singer leading the so-called reggae revival.

“Kingston does not have one up-to-date, state-of-the-art live music venue,” he said. “That’s absurd for the music capital of the world.” When he plays a show at home, he told me that he must personally invest upwards of JMD$1 million ($8,000 U.S.) in sound equipment to deliver a show up to his standards and hope that ticket sales will recoup the cost.

The Ward Theatre’s renovation, one of Kingston’s City of Music obligations, could be the answer. Built in 1912, the 830-seat venue sits empty and abandoned in the heart of downtown. The municipal government committed JMD$7 million ($56,000 U.S.) to renovate the facility, a project that Mayor Delroy Williams told me is on track for completion in March, though I saw few signs of refurbishment when I toured the venue in November.

Williams, however, is hanging his hat on the renovation. “The day the Ward Theatre is up and operational, that would be for us the start of Kingston taking its rightful place as the capital of the Caribbean Sea, pearl of the Antilles,” he told me in his City Hall office.

Others are more skeptical of the timeline on the promised renovation. Noting that the city government still hasn’t delivered on a promise to replace parking touts with meters or paid stickers, Christopher Lue, president of the Jamaican Institute of Architects, told me, “Just like everything else in Jamaica, talk and no action.”

In the era of the Noise Abatement Act, venues are a vital concern for up-and-coming musicians. Sevana, a 26-year-old rising star who is Protoje’s protégée, moved to Kingston at age 16 to be in the heart of the music industry. She charted internationally two years ago and is poised to ride the reggae revival wave, but just hosting a show locally is a challenge. On a Saturday night, I attended her fundraiser concert – a clothing donation was the price of admission. It ended at 11 p.m. — very early for Kingston. Held at an outdoor bar and restaurant on a residential side street in Uptown, the event attracted a more sophisticated crowd. Glasses of red wine mingled with the usual Red Stripe bottles and two Benzes were parked out front. But even with the comparatively low volume of an acoustic show that wrapped up before midnight, the evening’s MC made sure to call out some special thanks: “Big up the police for not locking down the dance.”

On a muggy weekday, I stopped by Jam One Yard, one of Kingston’s few remaining sound system yards where self-taught audiophiles coax new life out of old parts. Like many of Kingston’s musical wonders, Jam One was not obvious to outsiders, hidden behind a concrete wall topped with barbed wire at the end of a rough-paved, dead-end side street. But inside a zinc metal gate, a gravel enclosure that’s half a football field long revealed the raw material of Jamaican sound system culture. Under the shade of ackee trees, four men wielding power tools built amplifier racks while dancehall played in the background. Nearly a dozen people hung out at the Jam One Lounge, a bar and restaurant.

In an air-conditioned office filled with neatly organized bins of audio parts and stacks of turntables and DJ mixers, Jam One’s proprietor, Tony Myers, took a break to chat. A custom sound system starts at JMD$3 million ($24,000 U.S.), he told me, and sound system aficionados from Europe, Japan, and China come to his yard to observe the craft firsthand.

Alanna Stuart, a Torontonian of Jamaican heritage who records as Bonjay, spent several months in Kingston on a research and production residency, including an apprenticeship of sorts at Jam One. “Kingston is to music as Silicon Valley is to technology,” she said, arguing that a “sustainable innovation system” is at work in the city. “I could have learned what I wanted from YouTube videos, but it was my daily studio visits that taught me what the unofficial motto — ‘music is life’ — really means.”

Paris Dennis of Kingston band The Indiggnation performs. (Photo by Yannick Reid)

Such praise reflects Kingston’s international validation, but the day-in, day-out reality on the ground is difficult. Simply put, the Noise Abatement Act is bad for business, so Myers founded the Jamaican Sound System Federation to represent the industry. “We started the Sound System Federation to save the business,” he told me. “We have to lobby.”

Myers’ federation has about 70 members, down from a peak of 500 members in the now defunct Sound System Association of Jamaica, though he believes there are more out there who choose not to join.

On the wall, a poster outlines the four permits necessary for a legal event: Jamaica Music Society, Jamaica Association of Composers Authors and Publishers, Jamaica Constabulary Force, and Kingston St. Andrews Municipal Corporation (city government). The first two permits are for payment of royalties for songs played out by the sound system; the latter two are for permission to hold the event. Between hiring a sound system and paying for the permits and a liquor license, Myers estimates the cost to host a dance — even before paying for performers — at about JMD$45,000 (US$360), or about two months’ pay for someone making Jamaica’s minimum wage of JMD$140 ($1.12 U.S.). But with the 2 a.m. last call, he says there’s no way to make a living in Kingston’s late-night party culture.

“The session is gonna start at 2 o’clock,” he said. “No money is that gonna make.”

Myers doesn’t have a strong opinion about the entertainment zone proposal, except for one overarching priority that he believes should guide policy: “If poor people don’t make money, what do you think will happen?” he asked rhetorically, citing the economic activity that circulates around Kingston music events, from vendors selling beer, cane juice, and jerk chicken outside the dance, to the hair stylists seeing packed salons the day of, to the professional partiers (or “influencers”) who are paid by party promoters because their presence will bring the crowds.

Economic opportunities in the Kingston music scene provide employment in a tough economy and even drive down violent divisions known as “tribal war” between “garrisons,” poor neighborhoods usually ruled by criminal strongmen that have pledged fealty to either of the main political parties.

When it comes to the urban poor, Myers said, “If they’re not making money, we’re going to be in serious trouble.”

A street vendor named Carol concurred. I met her outside Weddy Weddy Wednesdays, one of Kingston’s longest-running current dances. It takes place on an Uptown block populated by bars, restaurants, a strip club, a pediatric clinic, a primary school and a tire shop. There appeared to be just one house in the immediate vicinity.

A single mother, Carol said that 11 years of vending chewing gum, cigarettes, lollipops, lighters and rolling papers has helped put four daughters through college. When the police shut down the party early because of noise complaints, she said it kills her business, but on a night like the one I attended, when the cops relaxed and let the 2 a.m. curfew run closer to 3 a.m., she can make decent money. Overall, she thinks dancehall culture is good for society.

“Sound system keeps down the crime,” she said. “It takes the stress out of your head.”

A few days after soaking up the vibes at Dub Club, I returned to chat with Selassie. A devout Rastafarian, he was cultivating three dozen cannabis plants under grow lights on the veranda, empty of visitors on a Wednesday night. From the city below, the sound of a church preacher percolated up the hill. The sound system was quiet, tucked under a cover to protect it from the rain.

He claims to have invested millions of Jamaican dollars in building up his sound system — a never-ending project. Six years ago he began opening up the space, which is also his home, to guests.

Dub Club’s growing reputation has sparked a cluster of sorts, with a half-dozen guesthouses and hostels now operating along this scenic stretch of the city. The night after I met with Selassie, a venue called the Reggae Legends Villa hosted Grammy-winning Jamaican dub pioneer Lee “Scratch” Perry, fresh off a U.S. tour.

Since the April incident, Selassie has gotten a tavern license for Dub Club and he hopes to get a club license. Those would at least stave off future police encounters over per-event permits, but they still don’t solve the dilemma that anyone, anywhere can file an anonymous complaint.

“The law is set up in a way that anyone can fuck up your thing,” Selassie griped. “The sound system is a dying culture in the land of its origin because of the Noise Abatement Act.”

That said, he recognizes that some people have a legitimate right to complain about music in a residential neighborhood, and as a fan of rasta roots music he wouldn’t take kindly to all-night dancehall or calypso next door. Still, he believes sound system culture deserves special consideration.

Mayor Williams is sympathetic but equivocal. “You have a culture that has developed, it’s our heritage, which is street dance. We’re wrestling that with the desire of our residents to enjoy the quiet of our homes,” he told me. “We can’t take actions that will rid our culture of events and activities that are central to the culture. You have to maintain the culture because the culture makes the city unique. It helps to identify the city.”

While the final decision is up to the central government, Mayor Williams at least seems to have been convinced of dancehall’s legitimacy: “Street dance is a Jamaican thing, it’s a Kingston thing, and it’s important to us.”

Gregory Scruggs is a Seattle-based independent journalist who writes about solutions for cities. He has covered major international forums on urbanization, climate change, and sustainable development where he has interviewed dozens of mayors and high-ranking officials in order to tell powerful stories about humanity’s urban future. He has reported at street level from more than two dozen countries on solutions to hot-button issues facing cities, from housing to transportation to civic engagement to social equity. In 2017, he won a United Nations Correspondents Association award for his coverage of global urbanization and the UN’s Habitat III summit on the future of cities. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine