Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberIt was a bright day last March in the village of Lamu, on Kenya’s northern coast. Mwai Kibaki, Meles Zenawi and Salva Kiir — the respective heads of Kenya, Ethiopia and South Sudan — had traveled to the sleepy town where they would mark the groundbreaking of a massive, multinational infrastructure project. Designed to jump-start East Africa’s economy and give autonomy to new democracies, the project is the most ambitious attempted in this part of the world in a century.

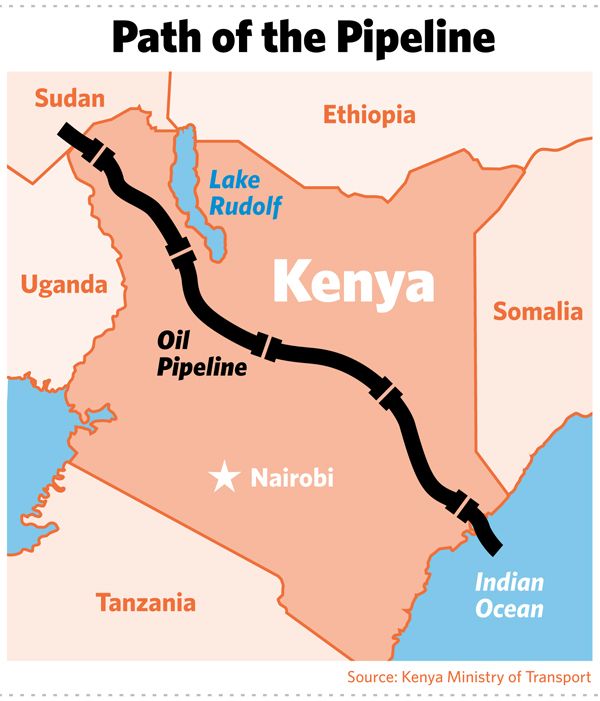

Each of the three men had good reasons to be there. For Zenawi, the project, known as the Lamu Port South Sudan Ethiopia Transit corridor (LAPSSET), would open distribution routes to accelerate his nation’s already-booming GDP growth. For Kibaki, the rail, road and tourism blueprints presented a chance to bring activity to Kenya’s dusty, impoverished north. For Kiir, the oil pipeline would free South Sudan from the indignities of exporting crude through its northern neighbor, with whom it spent the best of 25 years locked in bitter civil war.

To commemorate the occasion, each planted a tree of symbolic value.

Kibaki chose a fig tree, which, in Kikuyu folklore, gives the planter dominion over the land in which it takes root. Rather like the tribes that make up the majority of his country, Kiir’s tree was the tallest. Zenawi dug a hole and planted a tree as well. Today, both he and his tree are dead.

This is LAPSSET one year in. It’s hard to imagine that the site — now a ragged opening in the shore paved with mangrove stalks left to bleach in the sun — will one day become a massive shipping jetty. But the $24 billion idea is drawn from the oldest and grandest of planning instincts.

It was more than a century ago, in 1898, that this area last entertained a vision of this scale. Then, European colonizers started blasting a railway from Mombasa, another port city on the Indian Ocean, to Kampala, then the capital of British East Africa. Construction halted when workers hit the escarpment of the Great Rift Valley. They paused to contemplate next steps, and the dry highlands where they waited are now Nairobi, the region’s largest city. Most economic activity in modern-day Uganda and Kenya takes place within 50 kilometers of the railway.

LAPSSET will build another railroad, roads and resorts along a 1,700-kilometer proposed route, linking a new deepwater port at Lamu to the fledgling state of South Sudan. The port will host bulk, container and general cargo docks to supply the many landlocked countries dotting East Africa. Its rail and roads will steer through Ethiopia’s southern half. The keystone of the project is a pipeline and refinery to turn the region’s crude oil finds, confirmed and new, into cash.

The joint venture — approved in Kenya in 2010, signed as a memorandum of understanding by South Sudan in 2012 and inaugurated, with Ethiopia’s blessing, at Lamu — is also an unusual example of regional cooperation. Each participating government will finance the various moving parts. Addis is to provide electricity. Juba will provide oil. Nairobi promises to open the sea. Beyond the three main partners, landlocked Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and parts of eastern Congo also stand to benefit from cheaper imports and surer exports. It’s a revival of blueprints dating back to the 1970s.

If completed, LAPSSET will mean big changes to local politics and economics. Most obviously, the changes will be felt in idyllic Lamu, a region projected to swell from 100,000 to 1.25 million people over the next 20 years. In theory, the boomtown will employ dockworkers, machinists, engineers and an associated class of service workers. Some will cater to a new glut of tourists eager for flashy dance halls and casinos one finds in other coastal hotspots like Malindi and Mombasa. A housing and construction boom will spur promises of hospitals, schools and other services to support a more populous constituency. At the other end of the pipe, South Sudan will have a stream of oil revenue reliable and large enough to finally build the state of its people’s dreams.

In short, LAPSSET will be a test case for infrastructure spending as an economic development tool in 21st-century East Africa.

For many centuries, the Indian Ocean fed, and its trade lines enriched, millions of people in civilizations stretching from Mozambique to the Arabian Peninsula to Indonesia. Lamu, like many coastal communities in East Africa, owes its deep traditions and unique architecture to the hodgepodge of nations and languages that met along trade routes. A swirl of land and water just 60 miles from the Kenya-Somalia border, Lamu was a natural crossroads for the first wave of globalization.

Most of Lamu’s economy revolves around water, the only thing that resists the punishing coastal heat. At dawn, traditional Swahili fishing dhows leave for the open ocean, only to be moored in the shallow tide by midday. Men and young boys zoom along the archipelago in flat-bottomed speedboats, while traditionally covered women watch.

Lamu wields the kind of beauty that prompts resolutions never to photograph another sunset. It’s a UNESCO world heritage site and one of the best-kept touristic secrets in the world. Europeans have long flocked to Lamu for its white sands and fresh catch. Western holidays, especially New Year’s Eve, bring out the foreign and debauched. Many occupy the gleaming renovations in adjacent Shela town, where a plate of calamari will set you back the average monthly wage for locals.

Lamu has functioned as a sleepy outpost seemingly independent from Kenya for generations. LAPSSET will

transform this dynamic.

Though Lamu is technically a peninsula, the feeling is of an island in space and time. The main streets are too narrow for cars, leaving docile donkeys as the primary form of transportation. Winding through the warren of unnamed streets in search of coffee or commerce requires a stop-and-chat with half a dozen locals. Greetings are lengthy and obligatory. In the city square anchored by a massive shade tree, everyone seems to know everyone else.

Simultaneously, a diverse number of tribes — the Bajun, Aweer, Swahili and Sanye — inhabit the adjacent hamlets of Manda, Kitau, Kililana, Chiunga and Siyu. Nearby Paté Island has long hosted the descendants of Chinese seafarers. The archipelago remains one of the oldest continuously settled patches of Africa, a mirror to better-known Zanzibar to the south. Unlike the larger island that is now part of Tanzania, the Lamu archipelago never had its independence. Yet despite its lack of political autonomy, the village has long savored the sovereignty that comes with geographic isolation. Lamu feels like its own nation and it likes it that way.

That’s why a stalwart collection of civil society groups has been against the LAPSSET project from the start. Decades of underinvestment from the colonial and then the modern Kenyan political apparatus has led residents to mistrust initiatives from “up country,” as inland Kenya is known. Ali Obo, a member of the Lamu Port Steering Committee, sees LAPSSET’s ambitions as an erosion of culture. “As indigenous people [we] will be suffering,” he said. “We won’t even be seen. The whole Lamu community will be wiped out naturally.”

Another complaint is about culture. “They don’t consult us and they implement the project without our opinion,” said Walid Ahmed, a 26-year-old representative of Save Lamu, an umbrella organization advocating on behalf of locals affected by LAPSSET. “Our heritage will be destroyed,” he said, reflecting on the Lamu of his childhood. “When you come to Lamu, you can identify the way we are dressed… It was a good place, people used to come here to interact with Muslims, intermingle with the different nationalities.” He’s also worried LAPSSET will break the spell of small-town life and religious balance.

Beyond the intangibles of culture, real property is at stake. The Kenyan Ministry of Lands alleges that the port will displace 60,000 people. The agricultural economy revolves around land tenure: Cutting mangroves, farming maize, millet, cashew nuts and seasonal foods like mango. Farmers in the Lamu area claim rights dating back thousands of years, or at least hundreds.

“Land is a time bomb,” said Obo, who is also chairman of a farmers’ collective in the nearby Kililana settlement. “People depend on farming, they are less educated, they don’t have possibility of getting jobs.”

“We’ll have a lot of opportunity, but the opportunity will not be for the indigenous people from Lamu.”

The actual farming community is quite small — between 60 and 80 families — and, more than the ability to farm, Obo said, this group wants to be compensated for their displacement. Acquiring the necessary title deeds to communally owned land has been a hard bureaucratic slog. “The problem is there are so many sharks,” he said. “How is the land been surveyed? How do people have title deeds? They are mainly politicians and powerful people. The poor people are suffering.”

Adding to the controversy is the puzzling question of water rights. The vast majority of wage earners in Lamu are fishermen. LAPSSET will require dredging massive parts of the bay, killing coral reefs and potentially decimating the supply of crab, squid, lobster, snapper and other seafood that keeps the local economy going. There will be negative effects on marine life, like the rare sea turtles housed in an offshore sanctuary. While land title skirmishes are difficult, an existing legal and administrative framework governs them. By contrast, no such system of water rights has evolved in Kenya.

At a basic level, the port detractors in Lamu are making a complaint about process, not outcomes.

“It’s like getting married,” said Samia Omar, a 28-year-old woman who also works with Save Lamu. “Before getting married to a woman you don’t just pick them up, say ‘I fell in love with your daughter, we eloped, she’s pregnant.’” In Africa, Omar said, tongue in cheek, “if you want to get married, you come and talk to me. You ask ‘How do you want to marry her, when do you want to marry her, what is the price?’ Eloping is not consultation. African weddings are a consultation process.”

It’s hard to make the argument that Kenyan authorities have been a respectful suitor. By law, the government is responsible for conducting an environmental impact assessment, evaluating population displacement, land and water use, and other issues that LAPSSET might introduce. The government submitted that assessment only two days before groundbreaking at Magogoni — a timeline that made changing the plans or taking into account feedback difficult, if not impossible.

“It’s a mix of incompetence, arrogance and corruption,” said Omar, who grew up in Lamu and has consulted with the U.S. Agency for International Development on sustainable resource management both in Lamu and at Lake Turkana, the body of water in northern Kenya that anchors the LAPSSET corridor.

Adding insult to injury, the original groundbreaking with Kibaki, Kiir and Zenawi was held on a Friday, a day kept holy by the majority-Muslim indigenous residents of Lamu. As a result, very few local leaders attended, and most remember the snub.

Yet opposition to the project wanes once you leave Lamu and environs. “This land is Kenya’s,” said Joseph Kiragu, a civil servant from the central highlands who supports the port. During a recent interview, he took my notebook and pen to draw me a map of the East African region. “This is a path right here,” he said. “It’s a very sparsely populated place. Maybe 1,000 acres.”

When compared with the vastness of Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Somalia and both Sudans, the affected area seems small indeed. “It’s a national project,” Kiragu said. “So don’t displace a lot of people, look for where there are no people, displace a few and you will be able to compensate them. You can even relocate them to another area.”

But even with that logic, it’s hard to ignore the religious tension that underlies the conflict — a division between Kenya’s Christian central government and the overwhelmingly Muslim coastal population. The Mombasa Republican Council, an influential coastal group that advocates secession, has inspired a subset of like-minded Islamists in Lamu. I found conspiracy theories among ordinary people, some of whom oppose LAPSSET as a plan to punish the Muslim government in Khartoum. (The project will reduce oil revenue from the Muslim north in favor of the Christian south.)

“You are seeing this sympathy for this transboundary religion,” said Omar. “It’s very easy for Al-Shabaab) or any terror group to manipulate that.”

The play of identity politics, which led to violence after Kenya’s 2007 election, extends beyond religion. Gikuyus, Luos and other populous ethnic groups are said to be trespassing on territory of Somali and Arab coastal residents. The encroachment has roots in the 1970s repopulation of Gikuyu Central Province residents into Lamu. Recently, the potential bonanza of jobs at the port has drawn even greater numbers of upcountry Kenyans to the coast, alarming locals. “We’ll have a lot of opportunity, but the opportunity will not be for the indigenous people from Lamu,” Ahmed said. “This opportunity from the LAPSSET will be taken by people from up country or up continent.”

LAPSSET is being watched closely as an experiment in how shared infrastructure could benefit 21st-century East Africa.

Squabbling over property, religion and tribe is a stand-in for a greater battle over access to economic benefit. Lamu today is an economically depressed community. Apart from fishing vessels and tourist labor (often performed by outsiders), I saw none of the agriculture, manufacturing, construction or service activity — or schools — present elsewhere in Kenya. Unemployment among indigenous residents is astronomical, and idleness has left room for vices like drug use and trading to take root among young people.

Ahmed said that any upside to LAPSSET would bypass locals, in part because “the government [hasn’t] planned for our education.” It’s true that the educational offerings in Lamu proper are subpar. Ahmed was able to attend a polytechnic school after high school, but in Lamu this is unusual — many residents don’t complete studies beyond elementary school. While about 22,000 students are enrolled in public primary schools, the number plummets to 972 for high school.

Omar, who attended university in Canada, shares the same concerns. “Create jobs for who?” she said. “There is no one there with a college degree and a master’s in engineering. They will have a job, if they’re lucky, to dig the sand and construct [the port]. But after it’s built, there are no jobs.”

Whatever the cause, it’s hard to dismiss the sense that Lamu’s traditional Swahili culture hasn’t evolved to take advantage of the broader economic boom in the region. At the groundbreaking, Kibaki promised that LAPSSET would employ hundreds of local youth. “Those who are ready should come out even the day after tomorrow,” he said.

That hasn’t quite panned out. At Magogoni, there are approximately 30 jobs to be found. “I’m not sure it has benefitted them,” said Raphael Arudi, a 52-year-old contractor with Kenya’s Ministry of Public Works. He directs the mostly local crew hoisting cement bricks and assembling rebar at the building site. “We thought other companies were coming.” For now, they’re nowhere to be found. A quintet of laborers in yellow hard hats shouts jambo as their tractor rumbles by. Everyone else seems to be waiting for something.

At the other end of the proposed route, South Sudan is waiting, too. Locals form long lines for U.S. dollars every morning in Juba, the capital of the year-and-a-half-old country that was part of Sudan until 2011, when it gained independence after a bloody war with the north.

Large new hotels and other building projects dot the infant capital, but growing pains are evident. Electricity cuts in and out, and many people live in shacks. Infrastructure difficulties make distribution of goods both dangerous and expensive, and so everything — plastic buckets, mobile phones, motorbikes, linens and tee-shirts, limes, cheese, flour, radio batteries, razor blades, ceiling fans, Coca-Cola, you name it — is trucked in from elsewhere. This is the struggle of landlocked nations the world over. Here, years of conflict have only salted the wound.

Ronald Woro, an impossibly tall physician running a start-up private hospital in Juba, described the costs of the status quo. “We brought everything,” he said, walking through the wards of his hospital. “Two years ago it was a swamp, literally.” Everything from beds to blood reagents and x-ray machines are shipped in from abroad (Woro recently imported the country’s only CT scan). A diesel generator the size of an elephant lights the place when government power goes out. Unsurprisingly, these expenses impair Woro’s ability to help the sick.

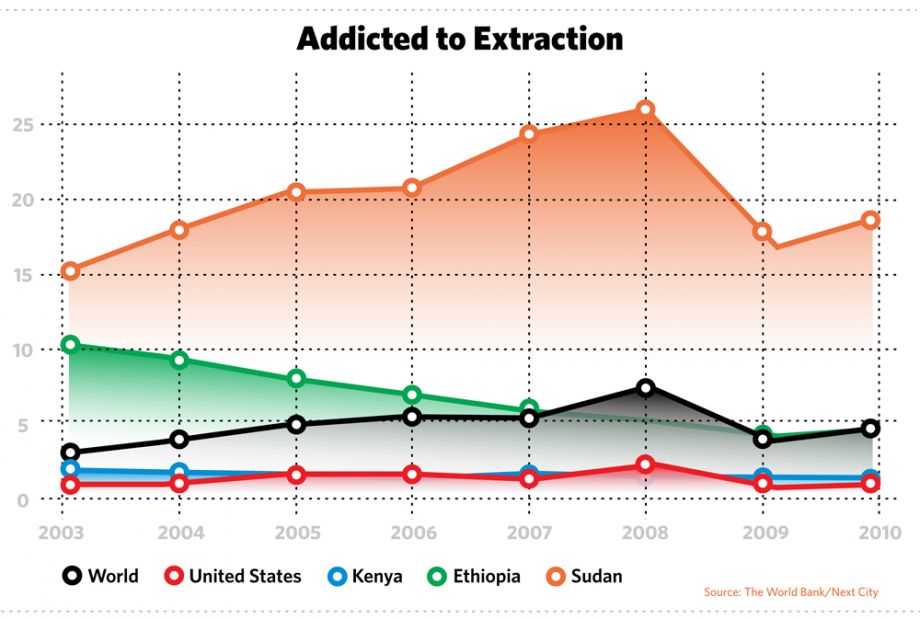

Sisyphean road ruts, expensive imports and stop-and-go electric distribution are manageable problems — at least compared with the problem of having virtually no revenue stream apart from oil. South Sudan counts on oil exports to produce 98 percent of the nation’s revenue. In contrast, the countries of OPEC count oil exports as anywhere from 27 percent of government revenues, in Norway, to 95 percent in Angola. While all these nations depend on oil, even a slight dip in oil sales is a mortal blow to South Sudan’s pocketbook.

Beyond the economic dependence, the infant nation’s oil supply is also an important point of pride. For many, that pride is worth more than cash. The systematic persecution of Sudanese in Darfur brought the country’s protracted conflict to international attention. But the grinding struggle between mostly black, Christian south and an Arab Muslim north has roots that go back decades, even predating British colonial rule. After a 2005 peace agreement and an overwhelming 2011 referendum, South Sudan jubilantly divorced the north, taking three-quarters of the region’s proven oil reserves with them.

The $2.4 billion LAPPSET project is a revival of plans dating back to the 1970s.

With independence came a certain stubbornness: Beginning in January 2012, the government in Juba refused to export oil through the northern pipeline that had financed the war of oppression. It was not a purely emotional decision: The north had been charging a usurious premium of $36 per barrel on the transmission of oil to the Port of Sudan. In fact, Juba’s abstinence was admirably nationalist. (Ethiopia, too, has rejected trade through neighboring Eritrea for political reasons.)

During the oil freeze, however, many new government-led construction projects were either stopped or slowed. Euro-style austerity measures cut salaries for the 70 percent of the population employed by the state, as well as the benefits that flowed to them and to everyone else.

The local effects were disparate, according to a prominent South Sudanese human rights lawyer who asked to remain anonymous. Various ministers and top-ranking officials began leaving large, unpaid hotel bills around town. Ordinary people fared worse, she said, but were still “ready to tighten their belts.”

“We’ve had it hard for five years so our grandchildren can enjoy the benefits,” said the human rights lawyer, who has been living in Juba since 2006.

David Akach, a 38-year-old from Jonglei state, described recent food shortages. “You go to the market, you end up with nothing. Things are quite different.”

“You have infrastructure and you don’t have resources, or you have resources and not infrastructure, or when you have both you don’t have the road for people to get there.”

But for a country desperate to build a climate of investment, the freeze was a red flag to foreign capital. Said one banking sector professional with several years working in South Sudan, speaking anonymously due to his position, “the foreign investors said, ‘Can we stay or wait?’”

The investors chose to wait, and so South Sudan caved. Just before I arrived in Juba, the north and south had inked an agreement to resume oil export. Sudan agreed to slash the tariff charged to around $10 per barrel, and South Sudan agreed to pay the north $3 billion in cash — a type of alimony for getting custody of so much oil. Then-U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who urged the agreement, stated the obvious: “A percentage of something is better than a percentage of nothing.”

But the terms of the agreement are almost irrelevant, as no one in South Sudan expects it to last. “The north has lied and manipulated since the beginning of time. Can we trust them?” asked the lawyer. She and assorted Jubans I spoke to were uniformly in favor of a new pipeline. In her office at the Ministry of Petroleum and Mining, Deputy Minister Elizabeth Bol expressed the idea simply. “We call it national independence,” she said.

Others put it in harsher language.

“We’d rather die not selling the oil,” said Moses, a 42-year-old ex-soldier, seeming to address Khartoum directly. “It’s ours. Don’t think about it anymore; don’t think of any techniques to get it back. We’re done with that.”

If the new pipeline is politically popular, the economics are more complex. To help cover the $24 billion price tag, Kenya has floated the idea of using infrastructure bonds, worth more than $150 million, to begin construction in June 2013. But more than a year after signing agreements and planting trees, Former Ethiopia president Meles is dead (he succumbed to an infection last year) and South Sudan hasn’t made clear its intended source of funding. The country is suddenly considering a pipeline that would pass through Ethiopia only — from oil-rich Unity State to Djibouti, Ethiopia’s longtime trade valve on the Red Sea.

Macar Aciek Akder, the undersecretary of Petroleum and Mining, who is actually negotiating the intergovernmental agreements, said South Sudan will follow the money. “The recommendation I will make will be based on economic analysis — what is cheaper,” he said. “Time-wise, other considerations-wise, finally it is this cost-benefit analysis. And the cost must be less than the benefit. Underline it.”

Akder is penny-pinching because, for a country so oil-rich, South Sudan is gallingly cash-poor. Foreign humanitarian assistance, both to the population and to the government, fills some of the gap. “We need everything from building schools to training media to training teachers to building hospitals,” said Amir Osman, senior policy analyst at the Open Society Institute. “If you talk to anyone in South Sudan, they’re relying at least 90 percent on donor support for the next decade, minimum.”

For 20 years, with growing frequency, the natural partner for comparable African infrastructure projects has been China. LAPSSET is no different. China National Petroleum Corporation is expected to manage the oil flows, and Japanese Toyota Tsusho is bidding for the chance to build the pipeline (a delegation from Toyota preceded my appointment with oil undersecretary Akder). But funding is less certain. Teams of Kenyan politicians and South Sudanese President Kiir have each made exploratory trips to Asia on behalf of LAPSSET and a pipeline to transport Uganda’s recent oil finds. Kiir came back from China with an $8 billion loan for national development projects, but no pipeline.

Awol Nhial, a young man originally from the Bahr al Ghazal region in South Sudan, believes Asia may pass on this bet. “China isn’t going to fund this. They already built a pipeline!” he said, referring to the Greater Nile Oil Pipeline in use since 1999 in Sudan. “[China] never expected separation. To build another [pipeline] they have to justify it, but it’s hard to justify… If a guy gets $2.4 billion to build a pipeline and then said ‘never mind,’ what are you going to think?”

Even if South Sudan can scrounge up the cash for the new pipeline (presumably by forward-selling current oil production), exporting through the north may be in its best long-term interest. The nation’s oil reserves may last only 20 to 30 years, perhaps five of which would be spent building a new pipe.

So a big pipeline investment is a tradeoff with South Sudan’s other urgent development needs: Schools, hospitals, affordable housing and electrification, to start. Austerity colored the country’s first round of post-independence budgets. According to the local banking sector professional, continuing to starve institutions and relying on foreign aid could backfire over the long term. “You have infrastructure and you don’t have resources, or you have resources and not infrastructure, or when you have both you don’t have the road for people to get there,” he said.

Of course, the pipeline is just one facet of the proposed investment. Bol, of the petroleum and mining ministry, emphasized the government’s desire to diversify revenues — “constructing railways and not just exporting oil, creating employment that will benefit, exporting agricultural products.” The railways, resorts and airports that comprise LAPSSET are attractive to a population currently served by fewer than 100 kilometers of paved road.

Others see an opportunity to build a larger and more formal agricultural sector. South Sudan, after all, has incredibly fertile soil, irrigated by the wide, flat Nile River. But it hasn’t had the opportunity to try feeding itself. Already, a few entrepreneurs — Daniel Gai and Peter Aguto, also from Jonglei state — are trying their hand at the farming techniques lost to the nomadic chaos of war. For them, investing in agribusiness is a way to promote food security and ultimately make use of the transportation infrastructure. “If we farm well, then we can proceed to commercial farming,” said Aguto, who officially represents the ministry of agriculture. Where Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania and even landlocked Uganda have leveraged transportation infrastructure to export fruits, vegetables and flowers, South Sudan could one day do the same.

The original Mombasa-Kampala railroad was nicknamed the “Lunatic Express” for its ambition. LAPSSET is no less grandiose or costly.

Unlike in Lamu, where locals harbor critical fears about displacement, compensation and rights, no opposition group has cropped up in South Sudan. But for both countries, LAPSSET comes with an opportunity cost of potential corruption and insecurity. Already, the geopolitical strings are showing. In late 2011, Kenya and Ethiopia invaded Somalia in the guise of retaliation for the kidnapping of Western tourists from Lamu. The ongoing military incursion is now said to be in the interest of protecting the port deal for investors.

In 2011, South Sudan lost $4 billion (that “b” is correct) to graft from its oil ministries. In Kenya, Mombasa is a natural experiment in what may go wrong with a major port on its coast. “Mombasa is congested and there is a lot of corruption,” said Arudi, the contractor selected to help build Lamu’s port site based on his years at Mombasa. “I don’t think the new port will solve the problems. It may even duplicate the problems.”

For all of the above reasons, Juba has yet to chart its route to the sea. The city has not conducted an internal feasibility study, and has blown past its defined timeline to do so. Partly responsible for the holding pattern could be the uncertainty following Ethiopia’s transition of power from Meles to new prime minister Hailemariam Desalegn — as well as Kenya’s elections in March 2013. Violent clashes during the last Kenyan election threw the whole East African economy for a loop. This time, however, both outgoing Kibaki and the slate of potential successors nominally support the port. “I don’t think the outcome of the elections will affect the project,” Akder said.

The pipeline is projected to swell Idyllic Lamu’s population from 100,000 to a staggering 1.25 million people over

the next 20 years.

But, as in Lamu, there are ample other reasons to pause. The unwieldy East African deal leads back to the same question facing governments around the world: Can you build a regional economy by way of infrastructure?

The answer is maybe. The original Mombasa-Kampala railroad was nicknamed the “Lunatic Express” for its ambition. LAPSSET is no less grandiose or costly. But even if every fear of land eviction, corruption, bankruptcy and environmental hazard comes to bear, the proposal does not discount the inherent value of state-sponsored Keynesian investment in infrastructure.

Scaling back the proposal, for example — roads but no pipeline, rail but no resorts — could actually prove this point. The original enticement may have been oil, but a properly functioning transit corridor would do just as much to unlock the hopes of the millions trading and producing along the route. It might do even better, as such a project could possibly have more support from traditional lenders like the African Development Bank, the International Finance Corporation and other private partners.

No matter what the outcome, the two poles on the Lamu-Juba corridor demonstrate the pitfalls and the promise of such a massive, multilateral infrastructure project. The cooperation showcases the new regionalism that is taking root across Africa. Borders are increasingly fluid. Ethnic, linguistic and commercial ties are becoming stronger than those of the individual nation state. The water will continue to lap the shore at Lamu, but who knows what will come with it.

Our features are made possible with generous support from The Ford Foundation.

Dayo Olopade is a Nigerian-American author of a forthcoming book on innovation from and for Africa. She has been a fellow with the New America Foundation, and written for numerous publications about technology, creativity and development policy. She holds degrees in Literature and African Studies from Yale University, where she is currently a Knight Law and Media Scholar.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine