Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

Pedestrians pass a mural of Father Harold Joseph Rahm near the intersection of Father Rahm Avenue and El Paso Street on Friday, March 31. (Corrie Boudreaux / El Paso Matters)

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

Become A MemberThis story was co-published with El Paso Matters as part of our joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellowship For Borderland Narratives.

If you walk around El Paso’s Segundo Barrio neighborhood, it’s hard to avoid the legacy of the city’s beloved bicycle priest.

Father Harold Joseph Rahm, who came to the city in 1952, served as an assistant pastor at the historic Sacred Heart Church for 12 years. In that short time, Rahm created a legacy that is still celebrated by residents: founding the Our Lady’s Youth Center to serve impoverished locals, creating outreach programs for low-income youth, working with gang members to clear their differences in the ring instead of the streets, riding his red bicycle around to reach community members in need.

Today, his efforts are memorialized in this Mexican and Mexican American barrio through several iconic murals, as well as a street that’s been named after him. But one of Rahm’s most critical contributions to the neighborhood has been largely forgotten: Creating the Tepeyac Credit Union, a pioneering financial institution to serve Segundo Barrio’s unbanked residents and protect them from loan sharks.

It’s a legacy that has largely been forgotten by El Pasoans, with several local historians telling El Paso Matters that they are not familiar with the initiative. But through archival research and an interview with one of the credit union’s early board members, El Paso Matters and Next City have begun to unravel that history.

The iconic mural of Father Rahm near Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Downtown El Paso. (Corrie Boudreaux / El Paso Matters)

It’s a history that illustrates community-based financial institutions’ power to support unbanked and impoverished people – and shows how such economic initiatives were a core part of major movements for social justice in the city.

The historic neighborhood in which Rahm served was known as South El Paso until several pockets were designated as Segundo Barrio, Chihuahuita and Duranguito in the 1970s. Banks redlined the community, making it challenging for residents to obtain financial services.

“People needed loans, and the banks at that time discriminated against South El Paso,” local historian David Dorado Romo says. “There were redlining maps in the 1940s that deliberately neglected areas marked in red. Since people couldn’t qualify for any kind of loans, especially not for home improvement…the community had to create its own credit union.”

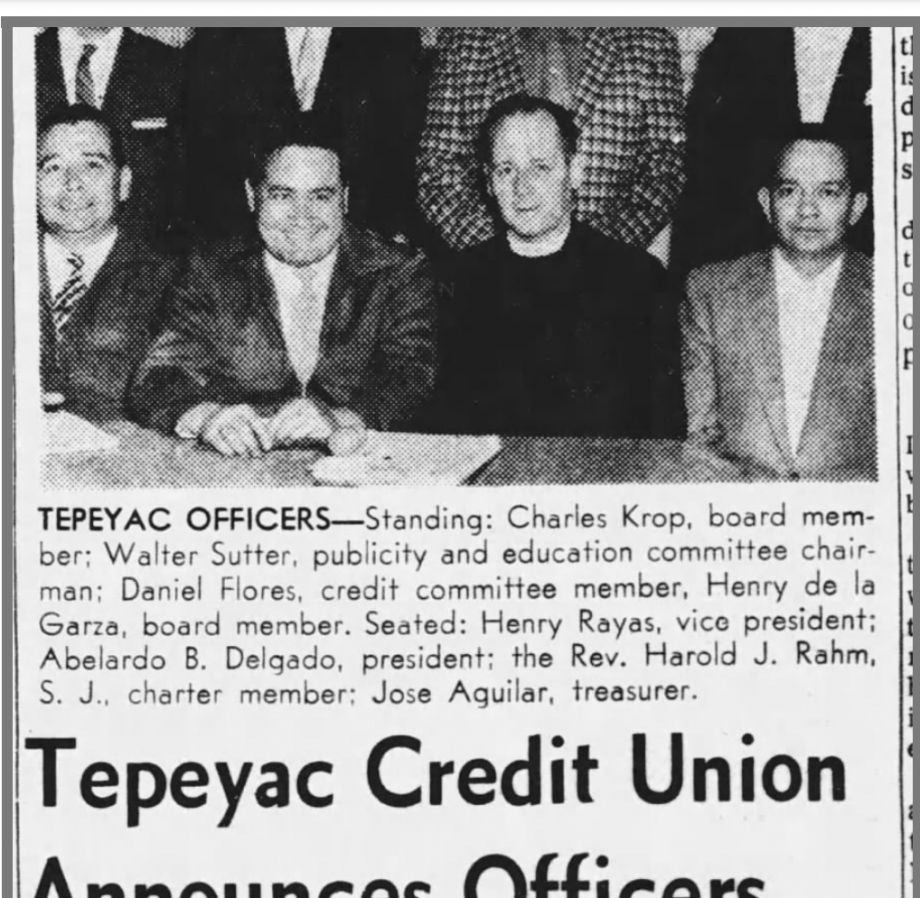

In 1961, Rahm banded together with a group of local residents and activists to create the Tepeyac Credit Union. According to Romo, one of these collaborators was Abelardo “Lalo” Delgado, the prominent Chicano poet from El Paso, who served as one of the credit union’s first presidents.

“He was one of the people that would go throughout the community and let them know that these kinds of services were available,” says Romo, who specializes in borderland studies. “Lalo, he was a great activist and also a very well-known poet.”

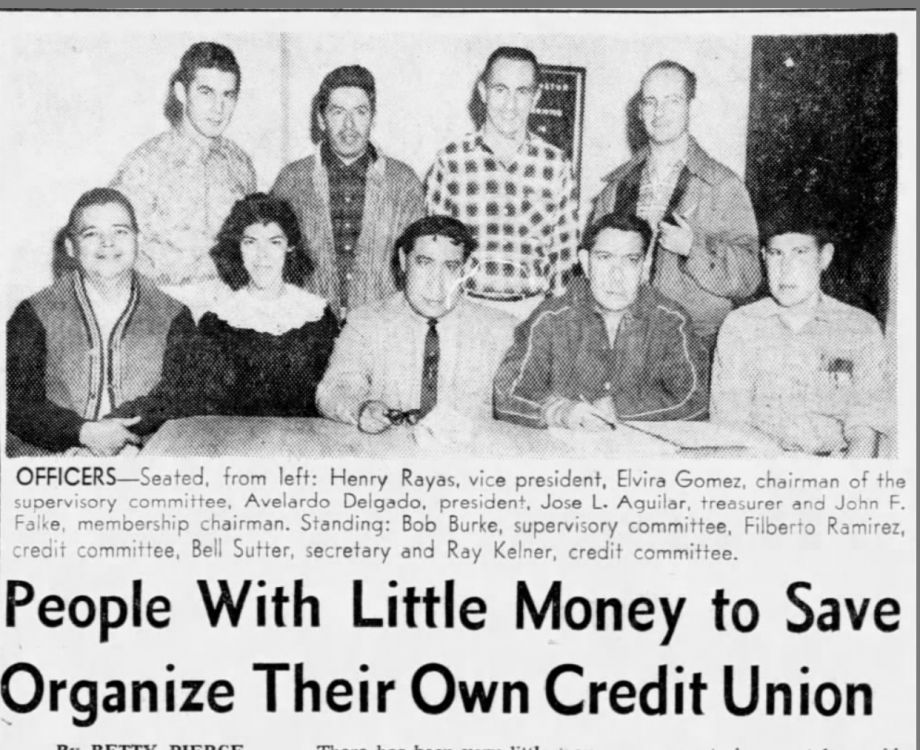

An Oct. 9, 1962 article in the El Paso Herald-Post documented the start of the Tepeyac Credit Union.

Delgado, who died in 2004, is considered the “abuelito” (grandfather) of the Chicano literature movement, pioneering writing that reflected a commitment to social justice and illuminated Mexican American heritage and struggles.

“He was our cheerleader,” says Felipe Peralta, an early board member of Tepeyac. Peralta had been a youth worker at the Our Lady Youth Center when he was invited to serve on the credit union’s board. “He was always motivating us to do more things.”

Father Rahm and Delgado collaborated at the Our Lady Youth Center — housed at the site of the Douglass Grammar and High School, which served El Paso’s Black students from 1891 to 1920. The center, created in 1953 and located at 515 S. Kansas, served as a home to programs for Segundo Barrio residents, including an employment center and the Tepeyac Credit Union.

The building went by several names, Peralta says, mostly “KC” – the Knights of Columbus. “Eventually, Father Rahm, I don’t know how he got a hold of it. But that was his operation.”

“That was a place that generated a lot of social movement,” Romo says. “They had a lot of outreach projects for youths, they had the employment center — they would find jobs for people at Segundo Barrio — and they created the Tepeyac Credit Union. It was a religious, social work project in South El Paso.”

Today, the notion of creating a credit union is unusual. In the past decade, only 25 credit unions have been chartered in the United States, as economic justice reporter Oscar Perry Abello reports for Next City. Before 1970, it was common to see 500 or 600 new credit unions chartered every year.

The original Douglass Grammar and High School on South Kansas Street in El Paso's Segundo Barrio was a school for Black children from 1891 to 1920. (Corrie Boudreaux / El Paso Matters)

Tepeyac only had two employees, according to Peralta: office manager Teresa Cordero and Mr. Flores, who was in charge of debt collection.

“(Cordero) did a lot of work for the credit union,” Peralta says. “Mr. Flores, whenever he was around the neighborhood … you would not see anybody else because his job was to collect delinquent accounts. I can’t remember too many people defaulting on their loans.”

Indeed, a 1971 El Paso Times article records that only 18 of 1,448 loans had gone uncollected.

“I remember even borrowing money for my second car,” Peralta says. “If I remember correctly, at one point, we had over a million dollars. It helped a lot of people to generate their credit. Once they establish credit with us, we will trust them with a little more money. It really helped a lot of people.”

A March 1961 newspaper article from the El Paso Herald-Post showed the Tepeyac Credit Union had potentially 30,000 members, between congregants in the parish at the Sacred Heart Catholic Church and employees and staff of Our Lady’s Youth Center.

“Much time, effort, and sacrifice went into the organization of this unique credit union,” the article reads. “Realizing the problems involved in setting up a credit union which serves a large low-income group, volunteer workers, El Paso Chapter of Credit Unions personnel and many others devoting themselves to the task of solving those problems.”

Father Rahm and a man named Ed Morrisey raised interest amongst the potential members, the El Paso Herald-Post article reads, while others held workshops to explain the idea and principles of operation of a credit union.

“Tepeyac Federal is considered a pioneer type credit union,” the news clipping says. “Prior to organization, its potential members had no access to credit union benefits and services. Experienced credit union workers now believe Tepeyac Federal Credit Union will not only succeed but will serve as a model … for the organization of similar credit unions elsewhere.”

The efforts of these activists helped create El Paso’s Chicano Movement for Mexican American civil rights, Romo explains.

“They were serving the needs directly of the community that this local city government or state or federal governments were not meeting,” he adds. “In 1972, when the La Raza Unida Party was organized, (Delgado) stood up and read his poetry to begin the whole conference.”

In El Paso, the credit union built upon the legacy of Mexican American sociedades mutualistas. These mutual aid societies focused on economic cooperation and community service, flourishing from the 1890s onward.

“It worked a little bit like credit unions,” Romo says. “Whenever people had an emergency sickness in the family, definitely for funerals. They were almost like community insurance groups. There’s a long tradition that goes back to the late 19th century, here on the border of Mexican American communities looking out for each other.”

Information on key figures within the credit union is difficult to come by, but a few names stand out in interviews and in news clippings. Peralta remembers John Falke – identified as the credit union president in a 1967 El Paso Herald-Post clipping – as a vital part of Tepeyac.

“He was a veteran or involved in the military and he did a lot of the groundwork,” Peralta says. “He would go out of his way to set up the whole thing.”

Another institution of Tepeyac was Henry Rayas, who served as president and is showcased on newspaper clippings from the early ‘60s for his involvement. Peralta suggests that it may have been Falke and Rayas who started the credit union.

A May 12, 1961 story in the El Paso Herald-Post.

“(Rayas) and his wife had 18 children,” he recalls. “Once the children grew up and were a little bit more responsible, they would come and volunteer there.”

Today, the credit union is no longer operating. Tepeyac’s latest statement of financial condition filed with the National Credit Union Administration was dated Dec. 31, 2003, showing $194,730 in total assets, 220 members and one part-time employee.

“I wonder what happened to (Tepeyac),” Peralta says. “We were doing so well.”

In December 2003, the Texas Credit Union Department received an application for Tepeyac to be absorbed into El Paso’s West Texas Credit Union, which had been chartered in 1964 to serve state employees in the area.

The state-chartered credit union “made a special effort to reach out to minority populations by offering a range of products that meet their particular needs,” according to a May 2002 hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs on brinking more unbanked and underbanked Americans into the financial mainstream. These products including low-cost remittances back to Mexico, an affordable housing program and Individual Development Accounts, a form of savings account aimed at helping low-income individuals save toward assets and build long-term financial stability through matching funds.

Credit unions like West Texas “recognize that consumers and their members must give viable options to avoid the traps of predatory lenders,” West Texas Credit Union’s manager testified in the hearing. “Credit unions have stepped up their efforts to combat predatory lendings in neighborhoods by offering affordable alternatives for both payday loans and mortgage loans.”

But after the credit union was “hammered by bad indirect loans,” per a Credit Union Times report, the National Credit Union Administration announced in 2009 that West Texas Credit Union had been liquidated “after determining the credit union was insolvent and [had] no prospects for restoring viable operations.” San Antonio’s Security Service Federal Credit Union purchased the assets that year and assumed the member shares of West Texas, which had had $78 million in assets and was serving 25,000 members at that point.

Peralta himself continues to be active in the community. He serves on the board of directors of Los Exes De La Bowie and Friends, a nonprofit organization that helps people with affordable housing.

“Everything that I have been fortunate to do, it has been because of El Segundo Barrio,” he says. After moving on from the credit union, he was involved with the Chicano movement. “My degree was in education. My goal was to teach at the public schools in South El Paso. But when I did my student teaching, I realized I was in over my head. Those kids were doing so badly that I knew that I couldn’t help them. So I went to try to help them with other stuff like housing.”

He looks back at Tepeyac’s board meetings, which also served as the credit union’s committee to approve loans, with nostalgia. “It was a really effective operation. It was one of the best things that we had going. Now that I look back at something that I feel we should have continued with.”

Christian De Jesus Betancourt is Next City and El Paso Matters' joint Equitable Cities Reporting Fellow for Borderland Narratives. He has been a local news reporter since 2012, having worked at the Temple Daily Telegram, Duncan Banner, Lovington Leader and Hobbs News-Sun. He's also worked as a freelance reporter, photographer, restaurant owner and chef. Born and raised in Juarez, El Paso became Betancourt’s home when he moved there in the seventh grade.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine