Are You A Vanguard? Applications Now Open

This painting, by the author's great-grandmother Josephine (Giuseppina) Coccaro, shows the view of SPURA from the Seward Park Coops. (Image used with permission of the author; photo appears courtesy of the collection of Paul Viani and Winifred Bendiner-Viani)

This is your first of three free stories this month. Become a free or sustaining member to read unlimited articles, webinars and ebooks.

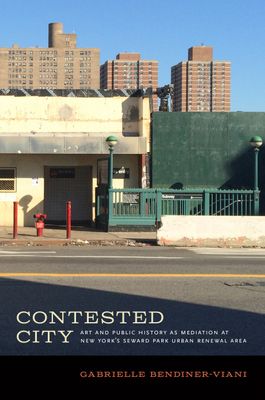

Become A MemberEDITOR’S NOTE: The following is an excerpt of the book “Contested City: Art and Public History As Mediation at New York’s Seward Park Urban Renewal Area,” by Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani, published by the University of Iowa Press. The book recounts the divisive history of a 14-square-block area on New York’s Lower East Side known as the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area (SPURA). When the area was razed in the 1960s in the name of “urban renewal,” thousands of low-income people of color were displaced with the promise of new, affordable housing that never materialized. Bendiner-Viani, an artist and urban scholar, was invited to enter this tense, disaffected community to support a new approach to planning, one that leveraged collaboration, community organizing, public history and public art. To hear more about the author’s Layered SPURA project and how it provided crucial opportunities for meaningful dialogue about the past, present and future of the neighborhood, register for Bendiner-Viani’s pay-what-you-wish Next City webinar on Wednesday, April 14, at 1 p.m. Eastern.

In all our community meetings, in our community projects, what do we mean by “community?” What are the terms of planning? What do we mean by “collaboration?” Who is the “public” for our work and for our exhibitions about the past and the present? What happens to partnerships in the long term — the fifty years of SPURA’s organizing or even the five years of our Layered SPURA partnerships? What labor is required to make this all happen? Here I want to explore the ways that the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area and its projects suggest that these definitions are mutable, unfixed, and that making your own definitions clear and being clear about those of your collaborators while seeing and making visible who has the power to set them, are at the center of this kind of work. It takes a specific kind of thinking and strength of will to question ideas that people think are simple or agreed upon. It takes a similar kind of thinking and strength to query or reject the premises, rules, and baselines of planning processes that city governments present to communities and neighborhoods as defining the realm of the possible. Without this kind of thinking and strength, our work isn’t worth doing.

One evening in late fall of 2008, with the weather getting colder, I walked from the Second Avenue F train station to the meeting room at University Settlement on Eldridge Street, where one of the many SPURA Matters community meetings was being held. These meetings and their following visioning sessions were imagined by the SPURA Matters coalition — in particular by Damaris Reyes of Good Old Lower East Side (GOLES), Marci Reaven of City Lore’s Place Matters project, Hilary Botein of the City University of New York, and Paula Crespo of the Pratt Center for Community Development — as a way to use public history to start a conversation before there was a plan to reject, and before the parameters of possibility for SPURA were set, yet again, by interests unconcerned with affordable housing and the area’s past.

We set up folding chairs, a screen at one end of the room, and a laptop and projector for the PowerPoint presentation as community members filed into the warm space. People greeted each other — longtime neighbors, friends, people who had lived on the Lower East Side for many years. Usually, Damaris introduced the SPURA Matters coalition and project and then turned the meeting over to Marci or Hilary, who fired up the slideshow and began the historical presentation.

People looking at an array of guided tour cards at the Layered SPURA booth, amid discussions that were part of the Creative Time show “Living as Form,” in the old Essex Street Market building. (Photo by Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani)

I had never seen history presented in this way, in this kind of place, for this purpose, playing this kind of role. The presentation was straightforward. Accurate. Almost dispassionate. It looked at the Lower East Side and explained the history of decisions made at SPURA. The story told was not an easy or optimistic one. It did not pull any punches in explaining the severe discrimination and disinvestment at the heart of SPURA. But the presentation placed that story in a living historical context, a larger picture, a broader fight for civil rights, for housing rights, for equality across the country. It placed that story in the context of political decisions and laws that affected many people and many cities around the country. In its very soberness, it clarified what had happened to the people who had lived at SPURA and the depth and importance of the issues they faced. But despite a story that is truly sensational, outrageous, and emotional, the presentation was none of these. For good reason.

This approach put people in a certain mood — not one of anger, which is how most other conversations about SPURA began, but one of informed thoughtfulness. Sometimes the history presented made people angry, but it was an anger that encouraged them not to declaim but to talk. The goal was to articulate clear and detailed statements about the past and about past wrongs so that the community members in the room could look to their own futures instead of reperforming their rightful anger about the wrongs of the past.

SPURA is inflammatory. Its whole history makes me wild with anger — even though decisions about its housing have not affected me and will not affect me, except as they affect all New Yorkers who care about the sustainability, equity, and heart of this place. For those people more personally affected, SPURA is deeply emotional; longtime activist Lisa Kaplan describes it as the place “that makes my heart race.” For many years, the empty space has been an open wound that many people carry with them. Sometimes simply saying the name is like rubbing salt in it.

Before these meetings began, the most recent proposal for the site had come in November 2003: a proposal to build three hundred low-income apartments and one hundred middle-income apartments on three of the sites, with commercial space on the remaining two. Supported by many of the activists who had fought for housing at SPURA for years, the plan was vehemently opposed by others, including some residents of the Seward Park Co-ops on the south side of Grand Street, buildings created as affordable moderate-income housing in the first phase of the SPURA urban renewal that have since gone market rate. The Villager described a “near-riotous crowd” at the November 18 meeting, with emotions running so high that the event devolved into a shouting match and police had to be called to calm the crowd, reporting that when “members of a group called Public Housing Residents of the Lower East Side, or P.H.R.O.L.E.S., unfurled a banner on the auditorium stage, [it] prompt[ed] a long and increasingly raucous round of chanting to ‘Put the sign down!’” As tensions rose, implicitly and explicitly racist accusations were shouted out. Some residents said that they felt that Community Board 3 was not speaking for the whole community. Juda S. Engelmayer, director of public affairs for UJA–Federation of New York philanthropy and a Seward Park Co-op board member, was quoted as saying, “They’re not really speaking for everyone who lives down there. … Businesses are starting to thrive, and apartment values are going up. Now saying, ‘Take all that and put more low-income or public housing in those areas, without considering the impact to people, businesses, and the community as a whole’ — some see it as a setback. Certainly not as progress.”

Other residents, however, said that the violence of this meeting made them angry, and they felt that discrimination and racism were at the heart of these discussions. Longtime local resident and organizer Lillian M. Rivera, who grew up in the neighborhood and with her family had been displaced from SPURA, explained, “They’re forgetting where people started from…. We’re low-income, not low I.Q. We’re decent people with families. These people stop and talk to me in the supermarkets. They know that I am not a bad neighbor. That offends me.” Valerio Orselli, executive director of the Cooper Square Mutual Housing Association, was quoted in the Villager as saying, “It’s very selfish for recent arrivals to complain about this kind of housing being built on this site when the housing they live in was built as affordable housing.”

Two letters to the editor in the Villager from before and after this event help describe two further perspectives. In a letter from the week before the meeting, Linda Jones, a co-op shareholder, noted that she had become aware of the plan to build low- and middle-income housing that would be presented at the November 18 meeting, and she didn’t feel that the residents of the Grand Street co-ops had been adequately informed:

There are 10,000 units of low-income housing already in this neighborhood. To me, this says that we are already over-saturated with these facilities … subsidized facilities should be evenly dispersed throughout the city, not concentrated in a single neighborhood. Some nice stores have recently opened. Just as things are beginning to look promising, we should not tilt the balance in the other direction by adding low- to moderate-income rather than market-rate or mixed-income housing.

The week after the meeting, Steve Herrick, the executive director of the Cooper Square Committee and a member of the Seward Park Area Redevelopment Coalition, wrote that he thought many opponents of low-income housing in the Seward Park area were misinformed. He called out the use of “terms like ‘public housing,’ ‘projects,’ ‘crime-ridden ghetto’ and other racially charged code words” at the meeting, saying that they had been used to discredit any effort to build economically and racially mixed housing.” He continued, “Many longtime residents were shocked to see the ugly display of race-baiting and shouting down of speakers,” and he suggested that there was more common ground than was usually acknowledged. “People of goodwill in this community are not that far apart in terms of what they would like to see built in Seward Park, but unfortunately some people want to sabotage any efforts to develop these long-vacant sites by stirring up division and miseducating the public.” The letter culminated by stating support for Community Board 3’s endorsement of forming a task force to develop a plan for the SPURA area and urged elected officials to do the same.

Our collaborator Damaris Reyes’s description of what happened at the community board meeting underscores the reasons why the calm of the SPURA Matters meetings was so needed. Damaris often uses a politic phrase, “members from the southern part of the neighborhood,” the location of the Grand Street co-ops:

… members from the southern part of the neighborhood were protesting because they didn’t want to see affordable housing in their neighborhood. And I was in that meeting and I was a recipient of that protest and I want you to think about what it might feel like to be in your own community, to be an organizer, someone who has protested for the greater part of their life, and … you are the recipient of people yelling at you, in your own hood, people that you went to school with, people … that you see at the supermarket. It was a surreal experience and it changed my life. And I knew that SPURA was going to be an issue that I wanted to work on. And it kind of makes me emotional sometimes, because I remember that day clearly. And to be able to turn that anger around and use it in this way was really powerful.

And so: this calm presentation on that night in 2008 to differentiate it from that other night in 2003. Right on the line between political and apolitical. But how and to whom information was presented — and for what purpose and what followed — made the meeting deeply political. The visioning sessions that followed, with surveys and planning exercises created by Paula Crespo of the Pratt Center for Community Development and a mapping exercise created by my students, got people to talk about their own pasts and, often in response to these, the futures they imagined for their neighborhood.

People talked about what they needed. What was missing from the Lower East Side. What they missed from the past. Instead of reacting to someone else’s parameters of a plan that already existed and needed to be mobilized against, to be fought, community members were speaking for themselves. This process, repeated over and over again in 2008 and 2009 in community centers and other spaces across the Lower East Side, contributed to the research findings outlined in the SPURA Matters report, “Community Voices and the Future of the Seward Park Urban Renewal Area,” which found that people deeply desired “housing for working-class and moderate-income households,” but that there was also interest in seeing mixed-income housing at SPURA.

These were probably some of the most civil conversations ever had about SPURA.

Excerpted from “Contested City: Art and Public History As Mediation at New York’s Seward Park Urban Renewal Area,” by Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani. Copyright © 2018 by the University of Iowa Press. All rights reserved. Use the code “BEN40” to get 40% off “Contested City” when you purchase directly from the University of Iowa Press, at the link given here.

20th Anniversary Solutions of the Year magazine