Improving energy efficiency in buildings could not only dramatically reduce carbon emissions, but could also reduce the energy burden on poor households, improve indoor and outdoor air quality, create green jobs, and save a lot of money, according to a new report by D.C.-headquartered research organization World Resources Institute (WRI). Each additional $1 spent on energy efficiency avoids more than $2, on average, in energy supply investments, according to the report; implementing efficiency measures now could also avoid locking in carbon emissions far into the future or requiring that buildings later go through costly retrofits.

With more than two-thirds of the world’s energy consumed in urban areas, the report outlines eight action steps city governments can take to improve sustainability in the building sector today.

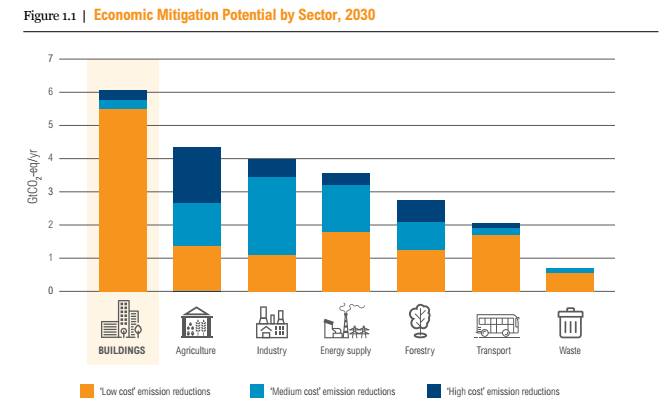

Compared to other industries, the opportunities for low-cost emission reduction in buildings are manifold. Lights can be connected to motion sensors to reduce waste; windows can be better insulated to keep in heat; buildings can be sited to optimize exposure to sunlight for warmth, light and solar energy production. And the benefits of implementing these simple interventions are just as many. The report cites a 2015 study of 61,000 buildings in North America, Europe, Australia and Asia that found higher sustainability rankings correlated with better financial returns on both assets and equity. Creating more efficient buildings also creates more and new types of employment. One study cited estimates that retrofitting 40 percent of the U.S. building stock would result in at least 600,000 additional long-term jobs.

Energy-efficient buildings can also contribute to a city’s resiliency and help alleviate the energy burden on poor households by reducing overall demand, even peak demand during extreme weather events. The city of Johannesburg, South Africa, for example, has implemented a set of basic energy-efficiency requirements for buildings that include natural heating in winter thanks to north-facing buildings and overhangs to increase summer shade, all to help protect residents during frequent power supply shortages.

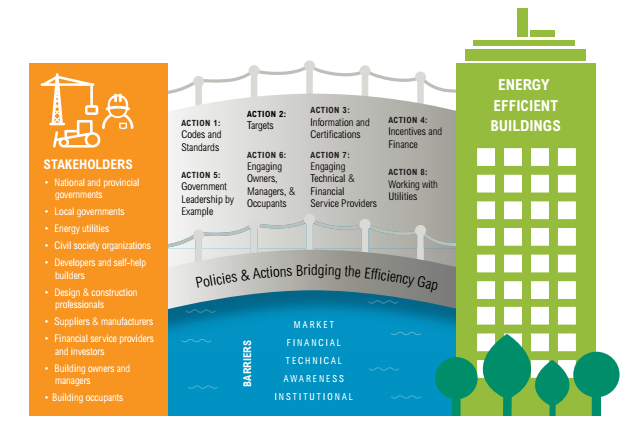

In the face of rapid global urbanization, and the quickening effects of climate change, more cities will need to adapt. The WRI report aims to arm local governments and other stakeholders with the roadmap they’ll need to overcome the technical, financial, market, awareness and institutional barriers to greater efficiency. The report breaks down interventions in eight action steps, as follows: Governments can (1) use performance-based building codes and standards to set a minimum level of energy efficiency in new or existing buildings, with requirements tied to the environment and economic climate. They can (2) introduce energy reduction goals at the citywide or community level, on a municipalities’ own building stock, or as voluntary targets to incentivize the private sector. South Korea, for example, has set a target that all new multifamily housing will achieve net zero energy by 2025, but the Seoul Metropolitan Government is aiming earlier, for 2023.

To help building managers, owners and occupants make informed decisions about their energy use, governments can (3) facilitate timely, transparent building performance data, by requiring energy audits, or energy performance disclosure requirements. In New York City, where owners of large buildings are required to annually measure and report on energy consumption, the city uses that benchmarking data to predict energy savings if owners were to implement certain energy-efficiency improvements. To help overcome the economic barriers to instituting such improvements, governments can (4) offer financial incentives like grants and rebates, energy-efficient bonds, mortgage financing, tax incentives, priority permit processing and more.

Local governments can also (5) lead by example, undertaking programs to improve the efficiency of public building stock, or mandating the procurement of efficient products and services in the public sector. Government agencies can further incentivize private building owners, managers and occupants by (6) providing support in the form of information, tools and technical assistance. Singapore, for example, has created a toolkit to help landlords and tenants work together on “green leases” that set out environmental objectives for a buildings’ improvements, operations, management and occupation.

Similarly, by (7) engaging the technical and financial services providers of the energy industry in training programs, cities can help improve workers’ understanding of energy-efficiency goals, or help financial institutions craft new mechanisms better suited to green technologies. The Investor Confidence Project, for example, aims to create a framework for how energy savings are calculated and measured in the U.S. and Europe, so that investors can feel more secure about the reliability of projected savings. Lastly, they can (8) engage the utility companies to improve customers’ access to usage data and to enact programs that help customers consume energy more efficiently, by allowing customers to repay retrofits on their monthly bills, for example, or pricing energy based on supply and demand, as Yokohama, Japan, does.

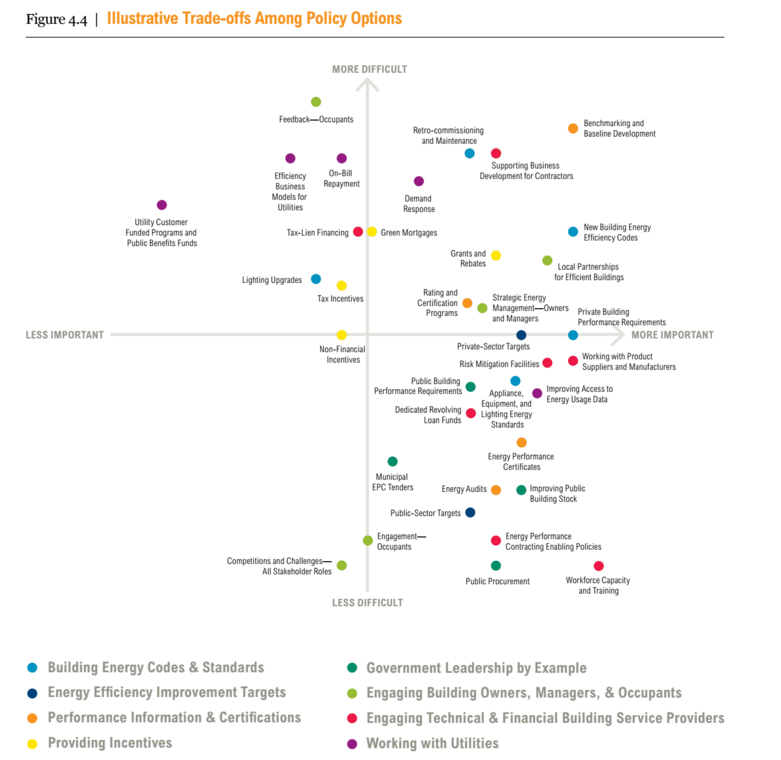

The report also breaks down the relative difficulty and importance of implementing various aspects of the roadmap, and teases out the different roles regulators, politicians, owners, investors and other stakeholders can play.

Citing examples from Cape Town to Singapore, where a green building master plan has helped increase the number of sustainable buildings almost 100 times between 2005 and today, the report acknowledges that different interventions are appropriate for different global contexts. It also stresses that opportunities for increased energy efficiency exist in every phase of a building’s life cycle, from land use and planning policies implemented at city scale, through design, construction, retrofits, operations and maintenance, and ultimately demolition.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_1200_700_s_c1_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)