The Motor City Mapping project, Detroit’s sweeping bid to map every one of its land parcels using mobile devices, has been in the news of late, most prominently with a profile by Monica Davey of the New York Times. That coverage, though, raises a few questions. The project’s stated goal is to help Detroit figure out its blight problem. But how, exactly, will the data fit into the ongoing political and social churn that surrounds blight? One part of the answer could come, it turns out, in the form of another mapping effort.

Preservationists are, in a project they call complementary to Motor City Mapping, creating a map of some of Detroit’s historic buildings. The hope of the Detroit Historic Resource Survey is to spare some of the architecture that give the city its character. Its relationship to Motor City Mapping, according to the survey’s creators, is that of a “preservation overlay.”

This is not an ordinary goal for preservationists, according to Emilie Evans, a specialist working jointly with the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Michigan Historic Preservation Network. “Preservationists are often thought of being always oppositional and antagonistic,” says Evans, who thought up the Detroit Historic Resource Survey. This stereotype, she argues, is a product of the fact that preservationists are often left out of decision-making process around buildings. By the time they get involved, she says, “they’re left to being reactionary.”

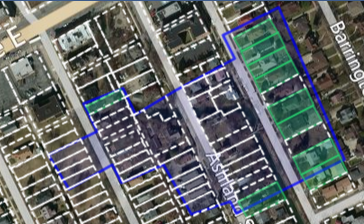

With the historic resource survey, Evans wants to put herself and her colleagues at the table when decisions about blight are made. One ticket to admission is a data set. Over a two-week period last month, Evans and her colleagues recruited about 50 locals with experience in architecture, historic preservation or architectural history to go out and assess nearly 18,000 properties in six targeted districts.

The blight mappers rated properties in terms of building quality — “good,” “fair,” “poor,” “suggest demolition.” But as Evans points out, “the way a building looks is just one piece of the puzzle.” The mappers also rated the homes on what matters to them: Things like architectural integrity, how much it keeps with neighborhood character, and the intactness of the block. A software platform called LocalData served up satellite views of the relevant areas. Surveyors would click a property and submit a rating, after which the parcel would turn green, letting other surveyors know it had been tackled.

An assessment on historic value is particularly important, Evans says, because of the nature of the money driving blight work in Detroit.

The cash comes from the Hardest Hit Fund, part of the 2010 federal Troubled Asset Relief Program, or TARP, aimed at preventing foreclosures. Michigan got about half a billion dollars in Hardest Hit funding, with $100 million focused on addressing blight, based on the argument that doing away with problem houses ups the survival chances for the rest of a neighborhood. Some $52 million of that went to Detroit, to be managed by the Detroit Land Bank.

The funds were, by agreement, exempted from a provision of the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act requiring federal agencies to take into account the effect of their actions on historic properties. The exemption, per Evans, “has our field of preservation up in a tizzy.” In practice, it meant that preservationists needed another way into the discussion.

According to Evans, the Detroit Land Bank and the Detroit Blight Task Force — the latter of which is, with the support of LOVELAND Technologies and Data Driven Detroit, leading Motor City Mapping — were amenable to preservationists piggy-backing off the larger mapping project.

Evans admits that notions of architectural integrity and the like are a bit esoteric to the non-preservationist, so through a “magic formula” built into an Excel spreadsheet, she and her cohort weighted survey results to come up with simple judgments on building values that preservationists can take into any meeting: “Very Important,” “Important,” or “Less Important.” The hope is that the data layer will factor into the mix in the same way that other data, such as crime, is combined with building quality to determine demolitions.

What risks getting lost in the conversation is that rehabilitation can be a blight elimination strategy, too. With the momentum — and money — behind demolition in Detroit, Evans says, “if we’re not super vigilant about what comes down, we’re going to lose some historically significant buildings.”

“Historic doesn’t mean that it was built by a now-dead famous person in an architecturally significant style,” she goes on. “It can just be a beautiful, simple house.” As long as a building is 50 years old or older, “historic” simply means that it helps define neighborhood identity, and thus the identity of Detroit. “No one famous needed to have lived there or have died there,” Evans says.

This new data set could give preservationists a proactive way to slot into the conversation around blight. “We’re often seen as anti-demolition,” Evans says. “We want to stand in the way of the bulldozer, blah blah blah. That’s not the case.” Part of coming to a middle ground, she says, is recognizing that not every building can remain standing forever.

“But in order to advocate for what we believe should be saved,” she adds, “we need to speak a language that everybody understands.”

Nancy Scola is a Washington, DC-based journalist whose work tends to focus on the intersections of technology, politics, and public policy. Shortly after returning from Havana she started as a tech reporter at POLITICO.

_600_350_80_s_c1.JPEG)