This piece originally appeared on Greater Greater Washington.

Open trip data lets researchers analyze bike sharing systems in detail. They are making useful discoveries about how culture and urban spaces affect the way people use bike share. These conclusions can help cities refine their systems as they grow and mature.

My recently completed master’s paper analyzes the factors behind the number of trips at different stations in Washington, D.C.‘s program, Capital Bikeshare. I created a regression of trips in October 2011 that began at stations in the District. After controlling for 14 variables, the analysis concludes that five key factors primarily determine a station’s usage:

• The population aged 20-39 • The level of non-white population • The retail density, using alcohol licenses as a proxy • Whether Metrorail stations are nearby • The distance from the center of the CaBi system

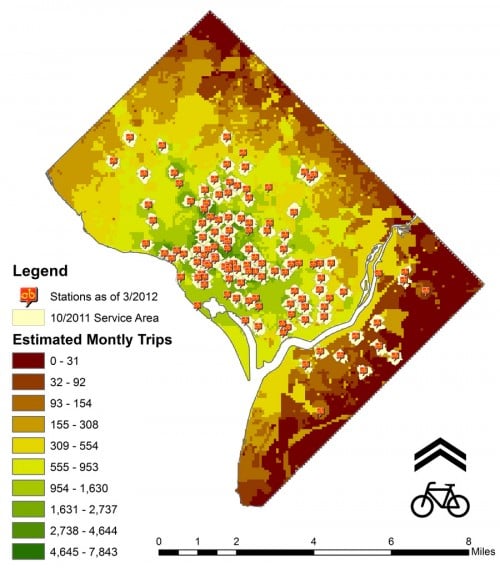

I measured each variable based on what’s within a quarter-mile walk of each station. With that information, I created a “suitability map,” seen above. For any spot in D.C., it projects how much ridership a station would get if the District placed one there.

The map shows that as you get farther from the main activity centers in central D.C., there’s a dramatic drop-off in station demand. Approximately 13 percent of Capital Bikeshare stations, as of March 2012, are located in areas where we would expect fewer than 18 trips a day. The actual usage data shows that a significant number of these stations at the edge of the system have even fewer trips.

There are equity reasons to place stations outside the core: Policymakers want to make sure that money spent on Capital Bikeshare benefits more than just those who live and work in central areas, and it builds political support from council members representing wards farther away. However, there are multiple areas around the District that are underserved by bike share today, yet highly suitable under the analysis.

Planners and policymakers should consider these areas as they build out and tweak the system in the coming years. The figure below shows the coverage gaps by overlaying the existing bike share stations and the suitability map.

Estimated number of bike share trips by station in Washington, D.C.

Credit: David Daddio

What can we conclude from this? The Washington region and other cities should consider the following issues when they plan and expand their systems:

Distance from the center matters. This variable accounts for 60 percent of the variation among station usage, by far the most of any factor. This matches a principle known as the “gravity model” in transportation planning, which predicts more trips between closer locations. Capital Bikeshare’s pricing structure also encourages shorter trips by charging for using a bike over 30 minutes, which strengthens this factor.

Carefully weigh goals of equity and coverage against ridership. It’s very important to provide active, multimodal transportation options to low-income and minority communities, and this study does not dispute that. That being said, it is important to carefully assess the tradeoffs among various objectives, especially in light of the relative costs of providing other mobility options for individuals of lower socioeconomic status.

Suburbanization of bike share has opportunities and pitfalls. The prospect of a region-wide bicycle sharing system in the nation’s capital is an alluring one to advocates. It is easy to imagine a robust, polycentric system around dense nodes like Alexandria, Arlington, Bethesda, College Park and Silver Spring.

However, some facts could temper that enthusiasm. Even some relatively close-in stations in the District have very low usage. Nearly 40 of the 97 stations in operation during October 2011 experienced 15 or fewer trips a day. Similarly, the densest parts of Arlington, with 18 stations during the same period, had 15 percent of stations system-wide but just 5 percent of trips.

To successfully expand bike share into the suburbs, planners need to choose station locations wisely, and elected officials need to invest enough to create a critical mass of stations early on. If we rush to build an inadequate suburban system, then it will likely not meet expectations and could act to blunt public support for the program, precluding a more economically sustainable system later on.

Stations can easily move as we learn more. Within a matter of hours, bike share operators can load stations on a truck and redistribute them to more suitable locations. While Capital Bikeshare operates year-round, colder cities like Montreal and Boston take their stations away each winter. Planners there use the spring launch of the system to refine the location of their stations based on station performance the previous year. Capital Bikeshare should schedule an annual station redistribution.

Promote open bicycle sharing data. Having this data available to graduate students and anyone else promotes transparency, scholarship, and innovation. Bicycle sharing systems are proliferating rapidly, which is very encouraging, but few systems nationwide release trip data.

For instance, despite $4.5 million in grants from public sources ($3 million from the Federal Transit Administration), data from Boston’s Hubway remains proprietary because of a private sponsorship agreement with New Balance. New York also hopes to fully fund its system with private dollars, which creates a danger that the same may happen there.

Like other North American cities, D.C. relied on international practices to plan its original system. Now, with an ample stream of data and more than $13 million in public funding committed to the regional system, it is time to strategically reassess station locations to ensure that bike sharing remains viable for the long term, as a true transportation investment.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)