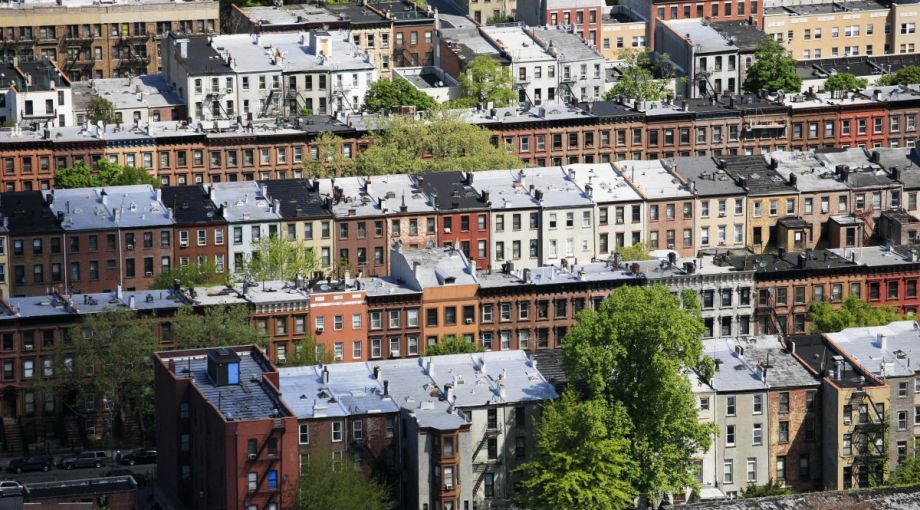

Last week, New York magazine published a provocative, but troubling excerpt from author D.W. Gibson’s new book The Edge Becomes the Center: The Oral History of Gentrification in the Twenty-First Century. Its frank description of real estate plunder in Brooklyn offers a rare glimpse into how race influences current-day real estate transactions.

In the piece, an anonymous Brooklyn real estate developer outlined strategies — many illegal and predatory on low-income black Brooklyners — to oust renters and property owners and replace them with white, relatively affluent transplants in neighborhoods that had been primarily occupied by residents of color.

“Ephraim” charged newcomers double what the displaced residents were paying, raising rents to prices that arguably reflect the new realities of demand in the neighborhood:

The building was full of tenants — $1,300, $1,400 tenants. We paid every tenant the average of twelve, thirteen thousand dollars to leave. I actually went to meet them — lawyers are not going to help you. And we got them out of the building and now we have tenants paying $2,700, $2,800, and they’re all white. So this is what we do.

In public conversations about displacement as the primary harmful outcome of gentrification, too often discussions focus on how “market forces” price low-income people out of their homes, without the necessary specificity that gives context to these “forces.”

Discriminatory practices like the ones Gibson and Ephraim recount co-exist and are intertwined with the rent inflation in neighborhoods caused by demand. Often the demographic overhaul in previously economically depressed neighborhoods is explained through the narrative of “millennials flocking to cities” or the congratulated success of urban revitalization.

Economists might argue that Brooklyn landlords like Ephraim are bringing rents and building prices up to their fair-market values, albeit in an insidious manner. Whether the means are “rational” or “natural” might not have that much value to actors in the business community, city hall, or oblivious members of the general public who are just happy to see a new pour-over coffee shop or commissary has opened on the corner.

Nonetheless, observers (myself very much included) owe it to dispersing communities to uncover the nature of how and why people depart communities.

One of Ephraim’s most incendiary and heart-breaking quotes in the article is when he says, “The average price for a black person here in Bed-Stuy is $30,000 dollars. Up over there in East New York, it’s $10,000 dollars.”

He’s referring to the price point at which a black tenant will take a buyout for their apartment, but he also unknowingly brings to mind the historic commodification of black bodies in the form of slavery. Black people in America are exhausted by the obliviousness that real estate interests and economic boosters exhibit when urban revitalization occurs and low-income people of color aren’t there to reap the benefits.

This week, I’ve been experiencing Detroit for the first time at the Center for Community Progress’ Reclaiming Vacant Properties conference. Over and over, speakers have emphasized that poverty, not gentrification, should be the priority of urban agendas. There’s a space where the two overlap that is underexplored. But more and more community groups and activists across the country are tackling what shouldn’t be a mystery. Philadelphia and Oakland groups have published reports called “Development Without Displacement” (read Oakland’s here and Philadelphia’s here).

We must also seek answers about why people accept offers like Ephraim’s and where they are moving — and if the money they accept ever actually puts them in a better financial position. Are there real estate development classes that could help build wealth in communities from within? Are there legal and financial resources tailor-made for low-income property owners exploring buying and selling? How are tenant protection laws being re-assessed and enforced? These are all questions I will be exploring in the future and will write about in this space.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Alexis Stephens was Next City’s 2014-2015 equitable cities fellow. She’s written about housing, pop culture, global music subcultures, and more for publications like Shelterforce, Rolling Stone, SPIN, and MTV Iggy. She has a B.A. in urban studies from Barnard College and an M.S. in historic preservation from the University of Pennsylvania.