Times Square, lovingly referred to as the Deuce, the Square, or Forty Doo-Wop, is New York’s capital of congestion. It’s this incredible crush of people, lights, buildings, and infrastructure that makes it the premier New Year’s Eve destination in the country. If estimates are to be believed, this New Year’s Eve should draw a million visitors to the Square.

This hyper-density, which is taken to the extreme every New Year’s Eve, isn’t an accident. Times Square is the paradigmatic example of Manhattanism, a concept developed by Rem Koolhaas in Delirious New York. “Manhattanism,” Koolhaas writes “is the one urbanistic ideology that has fed, from its conception, on the splendors and miseries of the metropolitan condition—hyper-density—without once losing faith in it as the basis for a desirable modern culture.” This describes Times Square to a T: the apotheosis of all that is good, bad, and somewhere between about New York shoehorned into a concrete bowtie.

The Square intensifies Manhattan’s already exaggerated density by compressing all of the activity along Broadway and Seventh Avenue into a tight five-block long space. But that’s just what we see on the street. Underground, the compression is even greater. Eleven subway lines snake beneath the street and converge at Times Square, making it the busiest station in the system.

All of this activity on the street and beneath it pushed the Deuce past its breaking point. Just as a balloon explodes after too much air has been forced inside it, the concentration of activities exhausted Times Square’s ability to function. In 2008, Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Department of Transportation Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan banded together with advocates and the business community to reclaim and redefine the iconic public space.

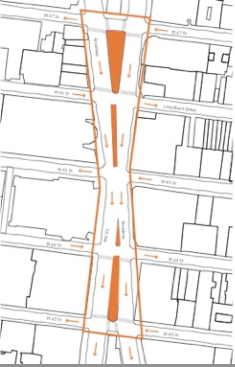

The central problem Times Square faced, at least in the eyes of this coalition , was automobile traffic on Broadway. Because Broadway stammers and stumbles its way from Greenwich Village to the Upper West Side, it cuts across the island’s straight avenues and creates non-rectangular spaces that disrupt Manhattan’s procrustean orthogonal grid. While these irregular shaped spaces provide Manhattan with some of its most iconic places, such as Columbus Circle, Herald Square, Madison Square Park, and Union Square, they also create tricky intersections that require longer red lights to accommodate the addition of Broadway’s traffic. This added delay frustrates drivers who must endure longer stoppages and confuses pedestrians who must stand at the corner for an additional light cycle before safely crossing the street.

First order of business: bring in the architect and urbanist Jan Gehl to tame traffic and improve the life between the square’s buildings. (Gehl Architects is also our partner in this column.)

Gehl found that Times Square consists of 89 percent road space and 11 percent people space, even though 90 percent of users are pedestrians.

The touristy square quickly became the bellwether of Gehl’s people-centered approach to urban design in New York. Through careful study of how the space was used by all users, from delivery truck drivers to the costumed superheroes who roam the crowds, Gehl and his team found that even though 90 percent of its users were pedestrians, only 11 percent of the space was allocated to them.

Working with Sadik-Khan, the Gehl team introduced designs for streets with new bike lanes and pedestrian plazas, carving out a little extra space for non-drivers. By New Year’s eve 2008, Broadway had been pedestrianized, with street furniture and meandering tourists filling spaces previously clogged with cars and idling buses.

Times Square before ( left ) and after (right) its “people-centered” makeover. (photo credit: NYC DOT/Gehl Architects)

The results of the Time Square project, dubbed Green Light for Midtown, returned mixed results in terms of improving traffic conditions, some streets saw faster travel speeds while others saw little or no change. In terms of collisions, safety and pedestrian volumes, however, the project proved convincing. The total reduction of injuries to pedestrians, motorists, and cyclists dropped from 75 to 46 injuries, or 39 percent, in the project area—the baseline data averaged observations from three six-month periods.

In addition, the number of pedestrians walking through the area increased by an impressive 11 percent, or an additional 2,000 people—this data reflects a sample based on counts taken at 20 locations and not a count of all pedestrians within Times Square. The city reported that 80 percent fewer pedestrians were walking in the roadways and that 74 percent of New Yorkers said that they saw dramatic improvement in the Square.

The configuration of Times Square wasn’t the only thing refreshed in 2008. As revelers counted down 2008 on New Year’s Eve, they were coaxing a newer, more energy efficient New Year’s Eve Ball down the pole and into 2009. In the spirit of grand spectacles, however, the new ball was outfitted with a staggering 32,256 L.E.D. bulbs—the initial ball back in 1907 had a measly 100 25-watt light bulbs in comparison—and it was announced that the ball would stay illuminated all year long.

Times Square has been a site of constant invention and reinvention for the last hundred years. Before the New York Times moved in at the turn of the 20th century, it was the center of the horse and carriage trade, which eventually moved farther uptown and ceded its turf to the nightlife and theater crowd. As movies upstaged musicals and plays, Times Square kept pace. Eventually, as New York fell into the social, racial and economic crises afflicting urban centers nationwide from the 1960s through the 1980s, Times Square became a neon-lit paragon of pathologies of the American city.

But the American city didn’t die in the 1980s, and neither did Times Square. With the coordinated efforts of city government, New York State, and the private sector, specifically Disney and a host of real estate developers, Times Square was remade into a place accessible to an idealized all: families, investment bankers, media types, cheering teenagers, tourists, and shoppers.

Even though the Square has been scrubbed clean and rigorously ordered by police supervision, an undercurrent of uncertainty and spontaneity—the animating element of all cities—continues to flourish here. No matter how Times Square changes, from its ongoing makeover to higher rents, the hundreds of thousands of people who flock to it everyday keep it alive as a vibrant urban manifestation of a global mass culture.

The health and vitality of our cities is not measured in job growth, median incomes, or plummeting crime rates, though these metrics are worthy indicators. Instead, it is the activity in our public spaces and on our streets that clue us into what we’re doing well and where we’re failing. The famed urbanist and scholar, William H. Whyte, studied America’s public spaces with the keen eye and pencil of a devout empiricist. “The street,” he said, “is the river of life for the city. We come to these places not to escape from it, but to partake of it.”

The column, In Public, is made possible with the support of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Eric Goldwyn is a doctoral candidate in urban planning at Columbia University. His writing on cities has previously appeared in New York magazine, the New Yorker online, and CityLab.