In the lobby of the 32-story Equity Building in downtown Boston, a screen on the wall informed me that the next red line train to Ashmont was due to arrive at nearby South Station in three minutes. The commuter rail to Kingston would depart in 17. And at the closest Hubway station (Boston’s bike-share program), five bikes were available.

I was checking out a TransitScreen, one of a handful now installed in the Boston area. (There are nearly 100 in the U.S.) The screen also had information on various buses, other commuter rail lines and Sidecar (two drivers were in the vicinity). The idea is to give commuters a sense of their myriad options at a given location. Nearly all of the data is “real-time”; the bus times, for example, come not from schedules but from GPS tracking.

TransitScreen co-founder Ryan Croft isn’t shy about his ambition for the technology: he wants to make it “ubiquitous in highly densely urbanized cities all around the country and all around the world.” When asked why this product is on screens in public places rather than downloadable as an app, Croft says that although they do have a mobile presence, “We see ourselves as a service for the masses.” They aspire both to reach the smartphone-less and to present people with this information even if they didn’t know they needed it. The theory is that people will become aware of choices they didn’t know they had, thereby making their travels more convenient and potentially adding to public transit ridership.

At the Equity Building, I met Patricia Walsh, the building manager, who had sought out TransitScreen. She wanted to provide a service like this to her tenants, most of whom, she said, take public transit, and a growing number of whom bike to work. “I called the MBTA, and asked, “Is there someone who does this? I didn’t even know what to call it.” The MBTA referred her to TransitScreen. “I was like, ‘Great. I’ll take it.’”

The TransitScreen was installed about a month and a half ago. During my visit, it was displayed on the lower right-hand quarter of a larger screen. Bloomberg News was playing on the left side, and on the right above TransitScreen, there were listings of upcoming building events (a concert, a car raffle). That right half of the screen added a congenial vibe to the lobby, a feeling that someone was looking out for the people who worked in the building. There was also something appealing about seeing so many modes of transit represented all together: It gave you a sense of the motion of the city, rendered in an accessible way.

But are people actually using it, and if so, how? Walsh said she hasn’t taken a poll, but has received a few positive comments. And though her tenants generally have a preferred mode of transportation (and carry smartphones, which can give them much of the same data), a quick glance at TransitScreen as they dash out the door can deliver helpful information. “If you see the train is in 20 minutes, you have time to run that errand,” said Walsh. “You can stop and mail that letter.”

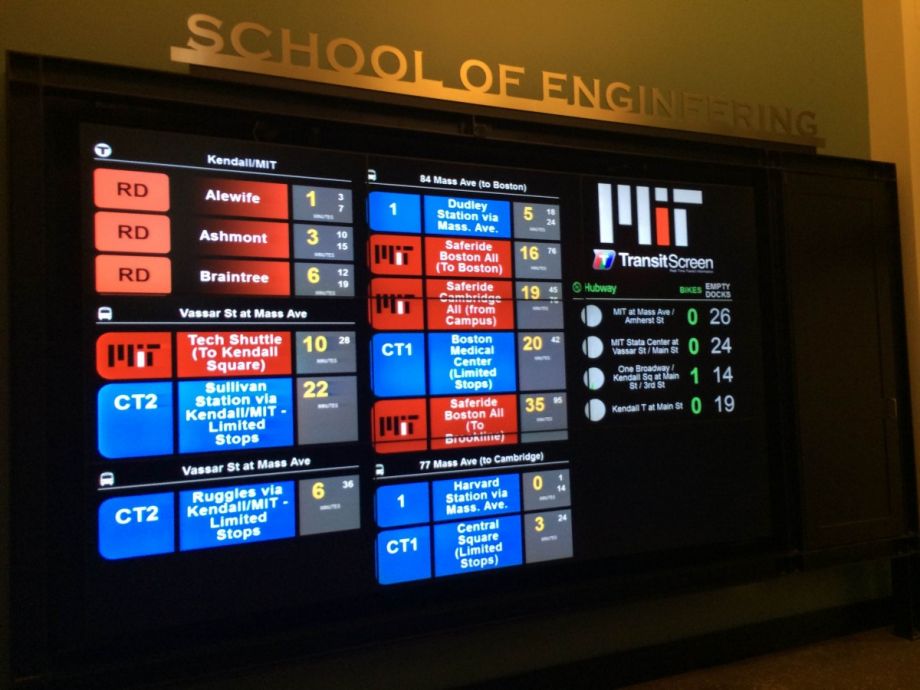

Earlier that day, I had dropped by the MIT School of Engineering, where another TransitScreen was on display, in a sparsely trafficked stairwell. This one was more elusive: Transit information appeared for about 30 seconds at a time, in between five-minute videos about robots and chemistry, making it difficult to study for long enough to make sense of it. Tyrone Scafe, an engineering TA, told me he had never noticed the TransitScreen info before. But would he find something like this useful? “I would probably just check my phone instead.” A young man from Ohio said it could help him, as a tourist, find his way around the city. A little knowledge of the transit system is necessary to interpret the screens, but in conjunction with a trip-planner app—or a friendly stranger—the real-time data about arrivals would certainly be valuable to visitors.

Back at the Equity Building, I asked several passersby if they used TransitScreen. One said no, she drove to work; one laughed and professed embarrassment that she never looked at it; another said no, because she takes the red line, which comes very frequently. Then, at last, someone replied in the affirmative: A man named Bill Kelly said that he consulted it; not to plan his departure, because he didn’t see it until he was on his way out — “but it’s sort of nice to know that I don’t have to run.”

When pressed about possible obstacles to widespread use, Croft explained that the hope is that people will start to use TransitScreen more as they grow acquainted with it. The lobby is “the first step,” but they also want to reach people at other “decision points”: internal lobbies, in street-facing windows, on desktops.

As for the notion that commuters already have their preferred mode, he replied, “that is exactly what we are trying to change.” The company is planning to add the car-sharing services Zipcar and Car2Go to their repertoire, as well as new private buses such as Bridj and some of the tech shuttles in the Bay Area. “We see a tectonic shift in the ways that people get around cities. These services didn’t exist two years ago or in some cases two months ago,” said Croft. “Cities are becoming extremely multi-modal.”

It may be too soon to judge TransitScreen’s ultimate utility; the installations are still novel and the screens and the transportation economy they represent are still evolving. As options proliferate, a mechanism to easily compare them all may become increasingly useful. Certainly for people who don’t have smartphones, this service could be a godsend. For those who do, it remains to be seen how many will look away from their familiar devices and up at the wall.

The Science of Cities column is made possible with the support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Rebecca Tuhus-Dubrow was Next City’s Science of Cities columnist in 2014. She has also written for the New York Times, Slate and Dissent, among other publications.