“First we will experience a fire, then a typhoon, then smoke, and then we’ll go back upstairs and do earthquakes.” This is how Yukita Minoru, an instructor at Tokyo’s Honjo Bousai-kan, earnestly begins our tour.

Built with funding from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s (TMG) disaster-prevention budget, the Honjo Bousai-kan, or “Life Safety Learning Center,” resembles a great stone pyramid hidden between apartment blocks on the east side of the city. Half of the facility is used as a fire station by the Tokyo Fire Department (TFD), while the other half is a public training facility whose goal is to prepare Tokyo residents how to survive the myriad disasters that befall the city.

Built in 1995 shortly after the Kobe Earthquake, the Honjo Bousai-kan is one of three disaster preparedness facilities operated by the TFD. Each center specializes in simulations of catastrophic scenarios. Yoshito Tsuge, assistant to the section chief of the Honjo Center, calls these simulations “disaster experiences.”

Entrance to all three Bousai-kan is free, subsidized by the TMG, as are the tour guides who lead visitors through their traumatic experiences. Thick with information and appropriately sombre, the tours are targeted at school-aged children as a means of teaching them what to do in, say, a high-rise fire or a tsunami crashing through their neighborhood. Beginning with a well-produced video of the tragic March 11 earthquake and tsunami, the tour moves from representation to simulation as groups choose what calamity they’d like to experience from a list of possible disasters: fires, typhoons, smoke, earthquakes, urban flooding.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, visitors to the Honjo Bousai-kan were French tourists and a group of local Japanese mothers who had brought their young children along for practice. The tour began with a digital projection of a fire which we were required to put out with real fire extinguishers. “This place is written in tourist pamphlets and, yes, some people come as tourists, too,” says Tsuge. “It is a museum of sorts.”

Calling it a museum, however, suggests a meditative experience. In truth, the realism of the interactive scenarios reflects the Japanese flair for high-tech horror. The experience is enough to cause an adrenaline spike in adults, and a hysterical breakdown in children. On the day I visited, I saw one mother lecturing her pre-teen daughter on the importance of training for disasters as the young girl sobbed loudly, traumatized by the typhoon simulator — the only one of its kind in Japan — which blasts its users with powerful winds and pelting cold water. Even full-grown adults emerged pop-eyed and shivering in their brightly colored rain suits, some of them clutching a supporting bar as the winds and torrential rain whipped their faces raw.

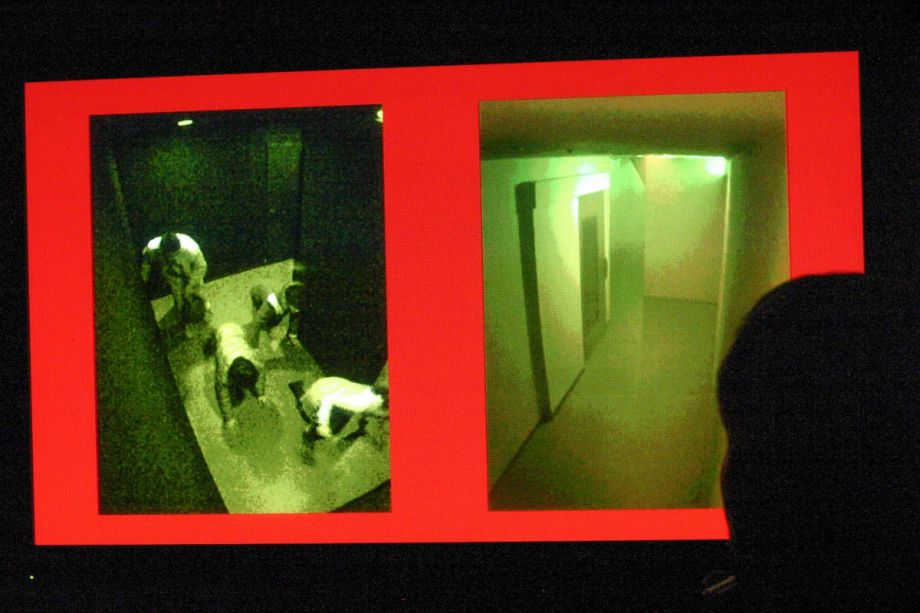

A closed-circuit TV shows people in the smoke maze.

Our guide didn’t sugarcoat anything as he highlighted the terrifying harm and suffering that results from each disaster, using anecdotes, statistics and graphics to emphasize his points. In the newest part of the center, a “smoke maze” built in March, he described in detail exactly how people die in fires before sending visitors into the darkened, haze-filled labyrinth.

Tsuge also highlighted the center’s new “urban flooding” corner, where visitors can experience what it’s like to try to open a house or car door when there is 20, 30, or 40 centimeters of water pushing against the other side of it. Twenty is easy, 40 is almost impossible, making the time-sensitive nature of clearing exits in a flood very real.

And, of course, there is the earthquake simulator, a fake room in which a small group of people are tossed about as the whole structure shakes violently, a sensation most Japanese are all too familiar with.

In 2013, around 12,000 people visited the Honjo Bousai-kan. “People of all ages came, but last year the government decided to push this more into school curriculums, and now more school-aged children have started coming.”

A tour guide pulls no punches in describing the horror of a house fire.

The idea for a facility that would prepare Tokyo residents for urban disasters was hatched in the late 1980s. When the Kobe earthquake which struck, it only emphasized the need for the Honjo Bousai-kan, which by then was already under construction. But how effective are facilities like this in terms of public awareness and readiness? Such outcomes are difficult to measure, but the TMG seems to think the centers are valuable, based on the continuous stream of funding it provides to the Fire Department for their operation. In fact, the TMG thought so highly of the concept that it built a disaster-preparedness center of it’s own, the Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park, an “experience-learning facility” that lets visitors practice trying to make it through the first few critical days after a disaster. “How would you survive during those 72 hours?” asks the center’s website.

The experiences in these facilities are a cross between riding a vomit-inducing roller-coaster and the horror of a real 7.0-magnitude earthquake. Comparisons with theme parks are inevitable. In fact, in 1990, five years before the Bousai-kan was completed, Universal Studios Florida opened “Earthquake: The Big One,” a 20-minute ride that takes parkgoers through an 8.3-magnitude quake based on Mark Robson’s 1974 disaster film, Earthquake.

According to Tsuge, the goal with the Bousai-kan is awareness and ensuring that Tokyo’s extreme disaster risk stays front and center in the minds of the city’s residents. But he knows that attracting visitors means making it an entertaining experience, so the center conducts plenty of workshops, holiday events and public campaigns. “We’re making posters for the new Spider-Man movie — they approached us to work on a campaign,” says Tsuge. The poster in question has already been displayed on community noticeboards across the city. Spidey, in his trademark suit and wearing a Tokyo Fire Department helmet, is surrounded by photographs of the Bousai-kan’s “disaster experiences.” Although the campaign is obviously more concerned with promoting Marvel Comics’ insect/human hero than the center, piggybacking on a Hollywood blockbuster could be just the way to capture the attention of Tokyo’s youth.

Photos by Cameron Allan McKean