The scene in SEPTA’s boardroom on Tuesday was one of glum resignation. Last week’s operating budget hearings — which addressed proposed fare hikes and the installation of a new payment system — were crowded, lengthy and attended by a diverse and occasionally boisterous crowd. Yesterday’s hearings on the agency’s capital budget were the exact opposite.

The sparse crowd, mostly made up of white people in suits, listened quietly as SEPTA’s capital budget director, Catherine Popp-McDonough, announced (again) that the agency is suffering from a “capital funding crisis.”

Alfred Achtert, a transit activist from Upper Darby, characterized the 45-minute hearing as “short, but not so sweet.” SEPTA’s current capital budget of $308 million isn’t nearly enough to attend to repair needs, let alone system expansion. (For perspective, NJ Transit’s $1.7 billion annual capital budget is four times the size.) According to SEPTA’s sworn testimony, “capital funding is at the lowest level in over 15 years,” while “ridership is at the highest level in 23 years.” But the agency likely won’t maintain, or grow, that ridership spike if services decline. To put it simply, a crappier experience for riders will probably depress demand.

“This budget is a disaster,” Achtert said, noting that the agency cannot raise revenue except by hiking fares further, which is a self-defeating idea. “Fare boxes, we all know or should know, can’t even cover the operating budget, let alone capital costs.” Those capital costs are only likely to worsen as old equipment breaks down, forcing costly repairs and delays, which will turn people away from transit and further congest roads.

Douglas Hall, another transit advocate, said that “the outlying years are looking scary.” If current funding remains the same, according to SEPTA projections, the agency will only have $2.5 billion to cover $6.5 billion worth of infrastructure and vehicle needs. That leaves 62 percent of the agency’s spending needs uncovered.

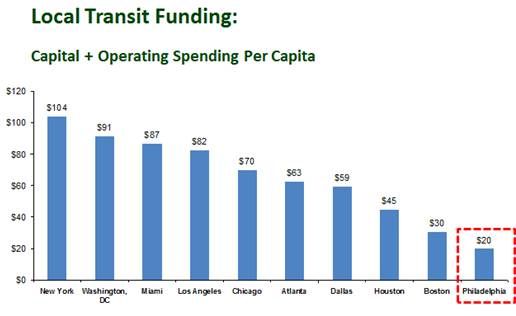

But these grim numbers didn’t stop anyone at yesterday’s hearings from dreaming, with speakers making suggestions that ranged from reinstalling old trolley lines to reopening defunct regional rail stations within the city, like the 52nd Street stop in West Philly. Grim reality won’t stop Next City from imagining what SEPTA should do if Warren Buffett starts feeling generous or, say, the counties started contributing a reasonable amount to the transit system they rely on. (According to Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) analysis of National Transit Database data, the Philly metro still contributes less local mass transit funding per capita than almost any other major urban area: Just $20 in comparison with $104 in New York City and $59 in Dallas, of all places. The five counties only contribute $4.2 million to the capital budget for the 2014 fiscal year.)

Here are five projects, some appearing in SEPTA’s capital budget, some not, on which the agency would break ground in an ideal world.

A SEPTA trolley in Media, Pa. Credit: Flickr user jpmueller99

1. Replacing the Trolleys

The aging Kawasaki trolleys that serve much of West Philadelphia, and the suburbs of Media and Sharon Hill, are more than 30 years old and are not compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Individuals in wheelchairs simply cannot ride these vehicles and, like anything else built in 1981, the likelihood of breakdowns and equipment failures grows with each passing year.

But it is essential that SEPTA maintain the subway-surface trolley lines — especially Routes 10, 11, 13, 34 and 36, which spirit riders through tunnels from the heart of Center City to University City and remove commuters from the congested arteries of downtown Philadelphia. If these trolley routes were replaced with buses, they would get people to their destinations at a slower pace while further cluttering the streets and fouling the air.

The cost of replacing the 141 Kawasaki cars and updating the system to comply with the ADA is $1 billion. (That also includes the cost of replacing 18 even older trolleys serving the Route 15 line on Girard Avenue in North Philly.) But the projected 2018-2025 budget only covers $85 million, or 8 percent, of the total cost. The remaining unfunded $920 million could single-handedly soak up SEPTA’s entire capital budget for three years running.

“In the best case-scenario, if someone dropped the money in our lap tomorrow, it would take five to seven years to replace the Kawasaki cars,” says Richard Burnfield, SEPTA’s chief financial officer. And considering the unlikelihood of a helicopter dump of trolley cash, it looks like this budget could expire without seeing systemic trolley car replacement. The Kawasaki trolleys would be nearly half a century old by the 2025 fiscal year.

2. Extending the Norristown High Speed Line to King of Prussia

Outside of Center City, the suburb of King of Prussia contains a greater number of private-sector jobs than almost anywhere else in the region. But the web of regional rail lines that spider out from Philadelphia doesn’t touch the area. The only way to get there is by car or by SEPTA’s 123, 124 and 125 bus lines.

SEPTA and other regional actors have been studying an extension of the Norristown High Speed Line to King of Prussia from its current final stop at the Norristown Transportation Center. The details, including price, aren’t concrete yet, but stops would certainly include the King of Prussia Mall and the Valley Forge Business Park, among others.

“I want to extend the Route 100 to King of Prussia, I want to do that tomorrow,” Burnfield said. “It makes all the sense in the world. [Current commuting] is all traffic dependent. Some days it’s a nice ride, some days you are stuck in traffic like everybody else. That area is already so congested, all the buses are packed. And I know — I live out there and I see them every day.”

City Hall station. Credit: Flickr user skabat169

3. Rehabbing City Hall station

The City Hall complex serves as a connection between SEPTA’s two most trafficked lines, the Broad Street and Market Street heavy rail, but the station itself is a decrepit subterranean labyrinth all but impossible to navigate by any but the most experienced Philadelphians. Built in 1928, it hasn’t been altered much since, which causes accessibility issues for disabled people and confusion and disgust for everyone.

“City Hall station is falling apart at the center of the line,” said Gregory Krykewycz, senior transportation planner for the DVRPC. “It’s being held together by rubber bands and chewing gum. It’s been the city’s top transit investment priority for a long time now… but the bulk of the work still needs to be done.”

The work is creeping along for the usual reason. “Due to funding constraints,” reads the SEPTA 2014 capital budget proposal, “only $48.6 million of the $118 million required to fully fund the project has been programmed in the last eight years of the capital program. The project’s construction phase will have to be phased or delayed until full funding is identified.”

Rehabbing a single station may not seem all that glamorous in comparison to installing light rail or extending the heavy rail lines. But the sheer embarrassment of City Hall station, at SEPTA’s very heart, is more than enough to win it a spot on the list.

4. BRT up Roosevelt Boulevard

The far northeast is poorly served by SEPTA. None of the subway-surface or trolley routes extend to these neighborhoods. To remedy that, the DVRPC’s “Long Range Vision for Transit” calls for an extension of the Broad Street Line up Roosevelt Boulevard as a subway-elevated line stretching to the border of Bucks County, at a cost of between $3.2 billion and $4.4 billion in 2008 dollars.

But if digging subway tunnels and erecting an elevated line would be prohibitively expensive, an enhanced bus system — known as bus rapid transit (BRT) — would achieve many of the same ends and for a far cheaper price. The idea is a bus line with fewer stops, more frequent service and a lane of its own, allowing for swift service unencumbered by other traffic, while lightening the congestion load on the other lanes. Roosevelt Boulevard is a thick cord of roadway splitting the northeast in two. It is more than wide enough to provide the necessary lane dedicated to a BRT service’s right of way. The DVRPC just makes a note of this as a temporary alternative to the grandiosely ambitious heavy rail plan, but BRT actually seems feasible if SEPTA were to ever secure an appropriate funding stream.

There is another possible BRT plan that would make the rounds of the city’s artistic and cultural delights, at a very reasonable $75 million price tag, but the Roosevelt Boulevard idea seems better calculated to reduce congestion.

SEPTA regional rail approaching 30th Street Station. Credit: Eric Harmatz

5. Making Regional Rail Right

Regional rail is great if you live or work in the suburbs and are catching the train during rush hour. Otherwise, it mostly just comes twice an hour and is horribly frustrating. Next City has explored some of the reasons behind this before, but inefficient allocation of the labor force isn’t the only problem. The system also struggles with bottlenecks: Segments of the rail that are single-tracked preventing SEPTA from scheduling its trains at a more frequent level of service.

Some bottlenecks are caused by outdated signal, switches and track interlockings, which SEPTA has been slowly but surely rehabbing. The Warminster Line, Doylestown Line and Chestnut Hill East Line have been fixed up, while the Chestnut Hill West Line, Manayunk/Norristown Line and Cynwyd Line are projected for completion by the fall of 2015.

But in some cases, bottlenecks occur because SEPTA trains run on tracks owned by Amtrak, which has first rights, or lines where freight has priority usage. The authority could systemically evaluate which of these are what Krykewycz calls “soft bottlenecks” — a matter of negotiation, feasibly solved by double-tracking a short segment of rail — and which are places with infrastructural or natural impediments. It seems like anything that can make regional rail faster and more frequent should be considered, especially in this magical fantasy scenario where money, and institutional inertia, aren’t such considerable hurdles.