Over the past decade, as the public has increasingly embraced the idea that food is best grown locally and sustainably, we’ve made the opposite assumption about our cultural institutions. Witness the “Bilbao effect,” recently declared all but dead in the New York Times. Smitten with the success of the Guggenheim’s outpost in Bilbao, Spain, we’ve come to believe that any city dissatisfied with its growth and tourist traffic need only follow a simple formula: Commission a big-name architect to design a bigger, flashier museum building, then wait for the tourists and tax dollars to come pouring in. And so we set to work turning culture into a cash crop, sowing boldface names and marble bricks like soybeans and corn.

But now groups of artist-entrepreneurs around the country have begun extending the locavore idea to the realm of culture. “Could we take the tactics from sustainable food production and apply that to art production?” asks Jeff Hnilicka, cofounder of the Brooklyn organization FEAST, short for Funding Emerging Art with Sustainable Tactics. FEAST, which celebrates its first anniversary next month, applies the logic of community-supported agriculture to grant-making: Locals pay admission to a volunteer-cooked dinner in exchange for the chance to vote on a set of artist proposals. The winning artist takes home the proceeds and presents the resulting work at the next dinner. Funded projects have included an underground library that circulates local artists’ work and a telegraph connecting the banks of the Gowanus Canal, inviting passersby to try tweeting in Morse code. This new incubator for art gives rise to an alternative economy that circumvents the usual gatekeepers and sets up a direct relationship between artist and audience. From Portland, Oregon, to Minneapolis, from Chicago to Buffalo, these groups are harnessing the principles of microfunding to strengthen their local arts communities—and, by extension, the cities that host them.

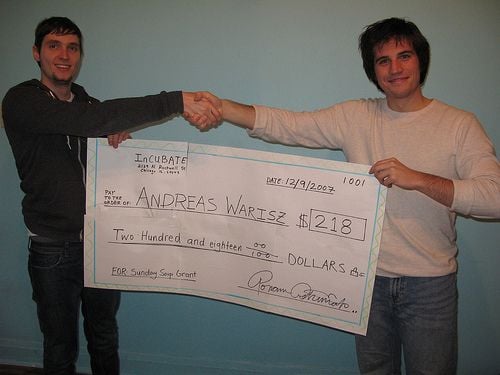

Right: A scene from Buffalo’s “Sunday Soup” event in April

Staged in a church basement in the Greenpoint neighborhood, FEAST looks like a cross between a downtown gallery opening and activity night at summer camp. At the October dinner, there were construction-paper streamers and kegs from one of the borough’s microbreweries, artist proposals tacked to bulletin boards and live performances from local musicians, crayon-drawn badges for the artists and a foodie-friendly butternut squash soup for everyone. When the votes were tallied, Hnilicka bounded onto the stage to present the winner with the night’s take—$1,200—in a canvas sack festooned with a giant glittering dollar sign, like a camp director stoking spirit for the talent show. “I’m from Wisconsin, so church food fund-raisers are in my blood,” says Hnilicka. FEAST takes a familiar format and repurposes it as the engine of its own miniature economy.

The idea of creating an alternative economy to support artists has roots in the socially minded art of decades past. “This kind of social practice involving food and community has been a part of artists’ practice since the ’60s and ’70s,” says Sarah Peters, associate director of public and interpretive programs for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. “There’s a reemergence of it right now.” Gordon Matta-Clark and Caroline Goodden’s artist-run restaurant Food, a SoHo fixture in the early ’70s, is one of the most-cited examples. Equal parts performance and egalitarian experiment, Food helped generate income for emerging artists and those working outside the gallery and university systems.

Now artists on the margins have attracted a new generation of advocates. “We saw that there are all these artists operating outside the boundaries of institutions, and they were having a really hard time getting funding,” says Abigail Satinsky, codirector of InCUBATE (Institute for Understanding between Art and the Everyday), a project space in Chicago that runs Sunday Soup, the original community-dinner-as-fund-raiser that inspired FEAST (a Sunday Soup award recipient is pictured at left). “I’ve always felt really alienated from the gallery version of art,” says Elizabeth Knafo, who with collaborator Dylan Gauthier won the most recent FEAST grant. “I’ve struggled a lot to figure out how to make art about realizing ideals.” Their project, called Green My Bodega, seeks to introduce the New York area’s abundance of local crops into the city’s abundance of produce-starved corner grocers.

The FEAST model is not out to supplant the role of traditional museums so much as to offer a reality check on the assumptions behind the construction boom of the last decade. “Many major institutions went and made these monuments to themselves that cost so much money to run and weren’t sustainable, and now they’re paying off those spaces and can’t run programs in them,” says Hnilicka. FEAST is fast, cheap programming, built to perpetuate itself—infrastructure to go.

After Sunday Soup’s debut in 2007, the format spread quickly to new cities, growing into a burgeoning movement just in the past year. FEAST came next, in February 2009, followed by Buffalo’s Sunday Soup in April and Portland’s Stock in July. In November several employees from the Walker Art Center founded FEAST MPLS (a scene from their event is shown at right; the group has no affiliation with the museum). Hnilicka, himself a former Walker employee, lent his organizing expertise to the Minneapolis group, and he is also consulting with nascent programs in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Though it’s highly portable, the model comes with a downside: It relies heavily on volunteer labor. In exchange for the freedom to operate without the restrictions of a nonprofit (boards of directors, bylaws, hierarchies of staff), the groups give up conveniences like event coordinators, dishwashers and, in Stock’s case, a venue that comes ready with tables, chairs, and lighting fixtures. Stock cofounder Katy Asher sees these sacrifices as a key part of the model’s appeal. “People come and they’re giving $10, but it’s not going to pay any of us tens of thousands of dollars to do what we’re doing,” she says. “It’s going directly to the artist.”

Like a community-supported farm, FEAST uses its recurring dinners to create a cycle of production and consumption, a reciprocal relationship between artists and their community. FEAST gives emerging artists access to cash and a captive audience, and in exchange for its investment, the audience is granted the power of the patron, a role traditionally reserved for the wealthy. “There’s something kind of crazy about art fairs where maybe 1,000 or 2,000 very wealthy people get to essentially decide what’s being consumed as artwork,” Hnilicka observes. FEAST creates a marketplace in which the bit players in the mainstream art world—emerging artists and the ordinary public—become the primary actors. In New York, you can pay $15 or $20 just to consume culture at a museum. At FEAST, you can pay $10 or $20 to help create it. “There’s an untapped market of families and people in this neighborhood that go and drop $20 or $100 at the bar or $40 on a babysitter and a movie,” says Hnilicka. “We’re tapping into a market that isn’t asked to fund an artwork.”

It’s a market that, as soon as it’s assembled, is interested in itself. The projects that the model attracts tend to take the form of idealist interventions in the community. FEAST awarded a runner-up grant to a local currency, and another proposal called for the installation of artworks on rooftops visible from elevated subway routes. And in Buffalo, the Sugar City collective, which runs a Sunday Soup program, heard from artist Kyle Butler, who wanted to pile sandbags in front of buildings slated for demolition. The sandbags would be mounted to wood structures shaped into giant, vertical 3-D letters spelling out phrases like “too late” and “look out.” “To knock down the house, you’d also have to knock down the artwork,” says Sugar City cofounder Aimee Buyea.

Creating a marketplace where consumers can transform into participants and producers is, for Hnilicka, a bit of economic activism. “I think there’s the opportunity to address the elimination of the middle class,” he says. “The middle class can create, can be really culturally vibrant and fund itself. But it does cost money.”

As happens in the original locavore movement, “sustainability” can be a code word for “sacrifice.” Making the FEAST model sustainable may mean integrating it into existing institutions that have the space and overhead to support it. But that kind of partnership is still a ways off. Though the Walker last year was exploring ways to incorporate microfunding into its programming, the museum has since dropped the idea. But Hnilicka remains optimistic. “Before you start a revolution, you have to start an alternative,” he muses. “We’re creating an alternative that can serve as a lab of ideas for what a larger institution could actually apply.”

Sugar City photo by Loren Sonnenberg. FEAST MPLS Photo by Sarah Davis