British author Zadie Smith made a name for herself with her debut novel White Teeth, a depiction of three families and two generations of Londoners bound together by unrequited love and a distant war. With its snapshot of multicultural, chaotic urban life, Smith drew comparisons to Charles Dickens for her panoramic illustration of the new millennium’s urbanites.

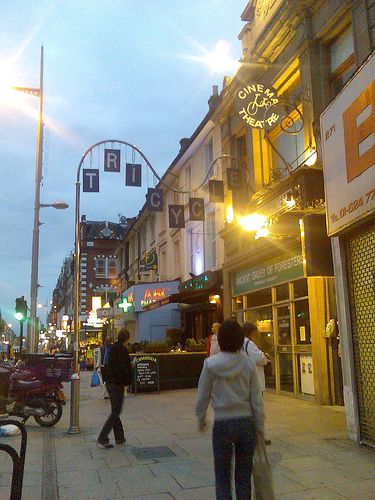

With her fourth novel, NW, Smith returns to her old stomping grounds. This time, she focuses on Northwest London, a formerly Irish area that’s well on its way to becoming an Afro-Caribbean one.

Most of the action centers on a part of the Northwest called Kilburn, where Smith grew up. Here’s how she paints a picture of the area as two of her characters go on a bus ride:

The window logs Kilburn’s skyline. Ungentrified, ungentrifiable. Boom and bust never come here. Here bust is permanent. Empty State Empire, empty Odeon, graffitistreaked sidings, rising and falling like a rickety rollercoaster. Higgledy piggledy rooftops and chimneys, some high, some low, packed tightly, shaken fags in a box.

Well-received novels like Claire Messud’s The Emperor’s Children or Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude have shown the tensions of contemporary urban life in the face of gentrification. Often set from the point of view of the gentrifiers, these books focus on liberals who wring their hands as they displace their low-income neighbors. Smith’s storyline similarly reflects the way class organizes a city’s population, but does so from the perspective of three characters: One who would never think to leave her neighborhood, one resigned to stay in Kilburn, and a third who did everything to get out but can’t stop looking back.

Likewise, NW is divided into three sections, each focused on a different set of characters whose stories overlap much in the way that communities rarely stay neatly wrapped up in little boxes of class or race or nationality. Any urban-dweller who has moved neighborhoods would appreciate NW’s depiction of the ways cities won’t let a group of people keep to themselves.

We begin with Leah (a London-born Caribbean) and Michel (an African emigrant), a couple at odds over money and children, whose choices illustrate how the anonymity of cities can facilitate a woman’s liberation from the expectation to reproduce. In the book’s second story, Felix, a filmmaker-turned-mechanic, decides to leave an older lover to fully commit to a younger one. In doing so, he chooses the relationship that locks him into Kilburn over the one born of his near escape from it. Lastly, there’s the story of Keisha, Leah’s oldest friend and good girl of the neighborhood, who did as she was told and managed to to become a high-powered barrister.

Kilburn, the Northwest London neighborhood where Zadie Smith sets her fourth novel. Credit: Mark Hillary on Flickr

One recurring theme in NW concerns the chance encounters that can change one’s life — the sort of chance encounters you can really only have in cities where walking is the main form of transit. Two moments of sudden street violence, for example, would not have happened had the characters been in a different place at a different time. Then there are also times when a character with nowhere to turn runs into someone they haven’t seen in years who takes them in a whole new direction. Most importantly, NW is a book of how cities force people with no reason to speak to face each other: The duke’s niece in love with the mechanic. The Pimp wandering the night with the lawyer. The hair stylist at the banker’s dinner party.

Much of the book’s tension is derived from the characters’ ambivalent relationship to their neighborhood. In Felix’s story, the lover he is leaving comes from a much-diminished noble line and has turned to dealing drugs from a walk-up apartment that she never leaves. Felix had nearly escaped Northwest London through filmmaking — now, in committing himself to a local girl, he seems to be embracing his fate as a man of the neighborhood, a mechanic in his father’s garage.

Keisha changes her name to Natalie to signal how she has moved beyond her roots. But when she doubts her life choices, she turns back to Kilburn in quixotic attempts to assuage her guilt for leaving. After finishing law school she first goes to work for a firm, but leaves it for Legal Aid work near home, in Brent. However, she can only take the work for so long before returning to much more lucrative law. When she feels the guilt of one who has risen, she tries to use her newfound wealth to rescue her mother and her sister from poverty — though they hadn’t asked for help.

The book makes it clear that Keisha becomes Natalie when she decides to stay with her banker-to-be college boyfriend. It’s a relationship that never exactly works for Natalie, but none of her relationships quite work. She neither feels at home where she’s from or where she has arrived, as if Smith is telling her readers that a spiritual homelessness is the price of taking a city up on the chance to escape one’s origins. A neighborhood like Kilburn, which in NW is very much a character with a will of its own, has no small say in where its people go and what they do.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.

_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)