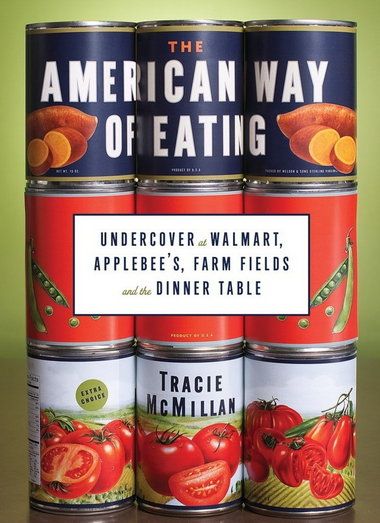

As an undercover reporter, Tracie McMillan saw firsthand how an exploitative food industry can marginalize laborers and keep whole segments of the U.S. population malnourished. It’s all chronicled in McMillan’s book, The American Way of Eating, which came out last month. An account of her time spent working in California fruit fields, a Walmart produce aisle and an Applebee’s kitchen, McMillan exposes the dirty secrets behind how food gets on your plate. This article is an excerpt from a section of the book in which McMillan works at a Walmart outside Detroit. On March 27, come to The Storefront for Urban Innovation at 2816 W Girard Avenue in Philadelphia to hear McMillan herself read from the widely acclaimed book. The reading begins at 6:30 pm. Click here to reserve a spot.

You have to sit on the porch; it’s a neighborhood institution. Gabriel has just come over to visit, and he is insistent, all but pushing me out the front door to a brick patio overlooking the street. We sit on plastic chairs with Bianca, who’s visiting from her apartment nearby, and her friend, Inez. Flowering baskets sway from the porch eaves in the humid spring twilight as we talk, and Bianca calls out greetings to everyone who walks past; she knows them all. It’s Saturday night, my first one in Detroit and the night before the city’s Cinco de Mayo parade. I’m still waiting to hear from Walmart about a third interview, so my weekend plans are to spend as little money as possible, which makes the porch an attractive option. There’s a festive anticipation humming through the neighborhood as glossy lowriders cruise the block, countered by the more sobering elements of the celebration: A cluster of candles that cropped up beneath a photo labeled “R.I.P.,” next to the telephone pole down the street; the police surveillance unit hat took up residence across from the park; the police helicopter thundering in broad circles overhead. All of this, explains Bianca, is because four people were shot during last year’s celebrations, including the young man memorialized in the shrine on the corner. The neighborhood, adds Gabriel, is one of the best in Detroit, but it’s still Detroit; he might be Mexican, but he wouldn’t walk around at night by himself, and definitely not on Cinco de Mayo. We keep talking: About Detroit, about how the city services keep diminishing, about work and the local lack thereof, about family and dating and school, about how drinking and driving is so accepted here that the police won’t pull you over unless you’re waving a gun out the window—and even then, says Gabriel, you’d probably have to be pulling the trigger.

The evening lazes on, and it might have just faded into bedtime except that Martina, Christina’s younger sister, shows up, striding up the sidewalk, kissing Gabriel on the cheek, and introducing herself to me. Gabriel leans over to her. You have to tell her about the foodie! Oh, are you a foodie? she asks me, a hint of challenge in her voice. After a few days of living with Christina, once it was clear that being honest about my work wouldn’t endanger my undercover status at Walmart, I explained that I’m actually a writer. Gabriel already knew all about it when we met, so I’m sure Martina’s already heard it, too. Well, I like food. I like to cook.

She sighs and tells me a story. So, I work at the radio station, and there’s this guy I work with, he’s younger, white, and he was talking and talking about these people called “foodies”; he’s one of them. So I ask him what that meant, “What’s a foodie?” And he goes, “It’s someone who’s really, really into food, and grows their own, and then does things like make preserves and pickles and cans their food.” Martina sighs again. “They’re like, really, really into food.” And he’s a foodie. And so I say, “Oh, like my mom, she does that.” Or, says Martina, leaning closer, she did, but now she’s old. But, when I was a kid, she used to grow all these herbs and tomatoes and chiles and everything, just like back on the rancho in Mexico. Gabriel looks at me. You’ve seen the garden, right? I nod: In back of the house there are two long strips of flowers and herbs, and plenty of room to grow food. You mean she would pickle jalapeños and salsas from scratch? And you could eat it all year? Just from the backyard? I ask, remembering the meals

I ate in Greenfield. Yes! says Martina. That used to be all food. And it was a pain, man, to help with that. But it was real good, too. I nod. Right. That’s totally the same thing! Right! says Martina. And so this guy, he says, “Oh no, not like that.” and I can’t get him to tell me what the difference is, he just keeps saying, “It’s just, like, you really, really like your food,” and I keep saying “Like. My. Mom.” And we go back and forth like this, and finally I just told him, straight up, “That’s classist, you just don’t get it.” And all he could say was, “Foodies really care about what they eat.” What does that even mean, says Gabriel, that you really care about food? I mean, I’m like, right, everyone likes food, says Martina. I like food, but I ain’t a fucking foodie, you know? I know, right? I like food, says Gabriel, slapping his belly. Look at my panza! We all laugh at this because he doesn’t have any belly to speak of, but they’re talking back and forth quickly now, old friends who can all but finish each other’s sentences. They nearly forget about me. Then Martina looks over at me. I’m sorry if we’re being too … Oh no, she’s fine, says Gabriel, winking at me. I think she’s a kindred spirit. Well, in that case, says Martina, smiling wickedly, we have to take her to El Chaparral. She turns to me, eyes sparkling in the streetlight. You want to see a real Mexicantown bar? I do, of course, and even though it’s only four blocks away, we drive over in Martina’s hulking Mercury sedan. We park on the street in front of a building I’d seen on my walks around the neighborhood. I’d thought it was abandoned, but now the door is open, and from the sidewalk we can hear patrons chattering in barroom Spanglish. All through Mexicantown, I don’t hear Spanish so much as its Anglicized hybrid, words swapped and traded and blended as they trickle out onto the street, sail out apartment windows, and roll out car doors.

Inside, we sit at the bar and Gabriel buys our drinks, PBR longnecks for him and me, and an iced shot of vodka for Martina, who takes a dollar from the bartender to feed the jukebox. She summons a flurry of guitars and trumpets threaded with deep masculine voices crooning in Spanish, and she and Gabriel throw their heads back and grin conspiratorially: I love this song! they say in unison. I smile, listening to lyrics I can understand but not translate, losing them in the hazy space between comprehension and definition. Gabriel nudges me to turn around, smiling, his eyes directing me to a couple swaying together over the beaten floor. The man, old, is missing a few teeth beneath his white mustache. His thick head of white hair is slicked back neatly, and his lips move softly with the song. He’s holding a woman who’s younger but not young, thickly built, her skin dark against a fuchsia tank top and denim miniskirt. He spins and leads her in some approximation of salsa, the soccer match on the television behind them drowned out by the trilling of mariachi trumpets. We’re sitting there in our tipsy reverie when a Spanglish exclamation yanks us back to reality. A woman at the end of the bar is holding her purse and slapping the counter, settling her tab. Ya me voy, porque I gotta work tomorra. The drunken lilt to her voice says it all, and the three of us cackle like teenagers at the back of the classroom. But when we finally stop laughing, I realize she’s at least got one up on me: I wish I had work to go to.

It takes three weeks in Detroit before I finally start at Walmart. There’s a third interview, where I accept the job; a drug test, at a remote medical office in an industrial park near the airport; waiting for results, and waiting, and waiting, for the store to schedule an orientation, a process that takes so long I begin calling other stores in case it doesn’t pan out. But finally, just past the middle of May, I get a call saying I am wanted in at 9 a.m. sharp for orientation on Tuesday.

As before, orientation passes in a blur of group activities, slickly produced video tutorials and a few personal lectures from staff about our roles on the floor. We’re a mixed bunch of orientees: There are two girls in their late teens who’ll be working in deli, a Latino guy heading for lawn and garden, a clean-cut athletic type bound for asset protection (that is, antitheft), and an intense, tattooed young woman who’ll be doing receiving at night. For produce, there’s me and Nick, a pudgy college kid who claims to be proficient in mixed martial arts. This is a brand-new orientation program, we’re told, since Walmart is shifting its focus onto customer service with the mantra “The Customer Must Win.” This does not mean customers are always right, just that they should always get what they want. There have been some other changes to the orientation since the one I had outside of Kalamazoo. Today, we’re earnestly informed that we should think about the store like Disney World: On the sales floor, we are “onstage,” and in the back rooms we can be considered “offstage,” except for the break room, since nobody wants to hear you talking about your job and what you do or don’t like about it while they’re trying to enjoy their lunch. This is also, I can’t help but notice, an excellent way to discourage employees not only from discussing their lives and forming friendships, but also from ever discussing work, wages, or conditions. It is, in other words, a way to keep us from ever whispering that dreaded word, union, which we learn in the brand-new Protect Your Signature video, is just another word for someone trying to steal our signatures by putting them on union cards.

The other thing I learn is that, as Walmart workers, we may well be responsible for our own injuries. During a safety presentation, we’re informed that if we get hurt on the job, the safety expert at Walmart will be sure to pull up the tapes. My concern about being branded a troublemaker is no match for my curiosity about this idea that workplace injuries—particularly in supermarkets, where injuries are more frequent than in construction—are the responsibility of individual workers.

So, if you lift something wrong, Walmart won’t cover it? I ask, picturing a harried scramble with the pallet jack, my knee wrenched, a pinched-faced woman hitting instant replay. Well, it varies, but you know what I mean, says Matt. Well, no, I don’t, and I’m pretty sure this flies in the face of basic workplace injury law, but I don’t say anything of the sort.

She’s going to watch the video and see if it was your fault, says Randy. Don’t try to be a macho man, a macho woman. Before I can hit the floor, there’s a parade of Computer Based Learning modules to slog through. I come in at 7:00 a.m. two days after orientation, as instructed, and find that I’m in better shape than most of the new hires, since a good share of my training from before has carried over. Most of my time is spent watching a series of videos that pertain directly to produce. All of them underscore the basic tenet of produce sections everywhere: If it’s not fresh, it won’t sell. This is an elegant bit of market-based logic that I find reassuring.

In Produce Operations, I learn that produce is a living commodity rapidly approaching its demise, and the produce section is nothing less than an expansive life-support system. There can be no slacking off over here, because 70 to 80 percent of purchases in the produce section are made on impulse—and “Mom,” Walmart’s target shopper, does not impulsively buy rotten lettuce. Naïf that I am, I had thought that most of the work in produce would be rotating stock in the back room and throwing out anything rotten, but there’s a hidden world of preparation and presentation—Trimming! Crisping! Merchandising!—with the singular goal of presenting our food as fresh, no matter when it came in the door, and thus boosting sales.

This is important because profit rates can be considerably higher in produce than in the average store department. But I’m not just handling produce, I’m handling food, just like everyone else in the Fresh Section—Walmart’s term comprising produce, bakery, and deli—so I sit through a double-feature dealing directly with food safety. The films—Food Safety 1 and Food Safety 2—seem mostly geared toward people preparing fresh food in deli and bakery, given the initial video’s focus on basic concepts like using a thermometer to check temperature and the vectors for delivering food-borne illnesses, though it occasionally dips into more broadly applicable topics like proper handwashing techniques and how to affix a hairnet. Part 2 goes into greater detail, highlighting the “Danger Zone” for fresh food—the temperature range between 41 and 140 degrees—and the importance of not leaving anything fresh in said zone for more than four hours, max. Little of this feels useful for produce—am I supposed to check the temperature of a cantaloupe?—but toward the end, everything starts to feel strangely familiar nonetheless. Then I realize why. I’ve heard bits and pieces of this before, in snippets from farmworkers and mayordomos, kitchen managers and line cooks. But in all the food jobs I’ve taken over the last year, this is the only time I’ve ever been given an actual lesson in food safety. My education concludes with Food Safety and Handling, a sort of greatest hits of everything that’s come before. It opens, like a lot of Walmart videos, to a soaring U2 guitar riff from “Beautiful Day” and cuts between shot after shot of comfortably middle-class families of varying ethnic backgrounds cavorting in their well-appointed homes, yards, and kitchens. Then we move to a joyless pair of corporate heads of something-or-other explaining why food safety is important. They offer two reasons. The first is that food safety is important because it’s the law, and if we don’t follow the law, we might have to pay a lot of money. The implication, of course, is that they might otherwise dispense with the food safety, an observation that inspires in me a new appreciation for food safety legislation. Once they’ve dispensed with this, the talking heads proffer the same motive that I’d like to think they kept in mind all along: We care about food safety because it’s the right thing to do.

A working-class transplant from rural Michigan, Brooklyn-based writer Tracie McMillan is the author of the New York Times bestseller, The American Way of Eating: Undercover at Walmart, Applebee’s, Farm Fields and the Dinner Table. Mixing immersive reporting, undercover investigative techniques and “moving first-person narrative” (Wall Street Journal), McMillan’s book argues for thinking of fresh, healthy food as a public and social good—a stance that inspired The New York Times to call her “a voice the food world needs” and Rush Limbaugh to single her out as an “overeducated” “authorette” and “threat to liberty.”

_600_350_80_s_c1.JPEG)