The motto of the Neighborhood Story Project is: Our stories told by us.

In the afterword to the first book the project published after Hurricane Katrina, Coming Out the Door for the Ninth Ward (2006) by the Nine Times Social Aid and Pleasure Club, anthropologist Helen Regis noted that, in the 200-year history of African-American benevolent and mutual aid societies in New Orleans, the groups had been widely photographed, written about, and otherwise documented by outsiders, but none before had published a book about its own social organization and its relationship to its communities.

“This book,” she wrote, “is making history.”

Our stories told by us. The notion first entered Abram Himelstein’s head in 2004, while he was an English teacher at John McDonogh High School. Each year, he filled a bookshelf in his classroom with titles he imagined would interest his students, and each year it would sit there, slightly dusty and mostly undisturbed.

“The idea of books did not seem very interesting to my students,” he says. “I realized that a lot of that came from them not having seen many books that spoke to their experiences.”

His colleague Rachel Breunlin was having better luck. She had been publishing ’zines of her students’ writing that were wildly popular at the school. As she and Himelstein discussed their respective situations, they came up with an idea: to publish a series of books that students would write about their own neighborhoods. With grant funding for the project, each student would receive a $1,000 stipend — a rare instance of working-class kids getting paid to do intellectual work — to conduct research and interviews, write memoir-esque essays and gather photographs to compile into ethnographies that told their own personal stories within the larger context of their neighborhoods’ and New Orleans’ history.

The first round of five books was a smashing success. Hundreds of people attended their release parties in 2005 and they became citywide bestsellers. Applications streamed in from students for the next round, but as Himelstein and Breunlin were in the process of going through them, Hurricane Katrina hit and scattered the residents of New Orleans across the nation.

In the introduction to Cornerstones: Celebrating the Everyday Monuments and Gathering Places of New Orleans’ Neighborhoods (2008), Bruelin wrote: “Each person (or nonprofit organization) has their own way of responding to disaster, and ours — as a community documentary program — was to document the vitality of New Orleans’ neighborhoods.”

In a city where many residents have generations-deep roots in their neighborhoods, and those roots form a large part of many people’s identities, it made sense to launch a neighborhood-centric publishing project. But after the storm, with tens of thousands of people unable to return, and with many of those who could forced to live in unfamiliar parts of the city, the project’s objective transformed from documenting the city’s rich social tapestry into trying to reconstruct it and save what could be lost.

“The Cornerstones project and the Nine Times project were looking at the people as the heart of the city — the physical landscape had to get rebuilt, but the social fabric had to be rebuilt, too,” says Breunlin. “The stories became these maps of relationships that were vital to people before the storm.”

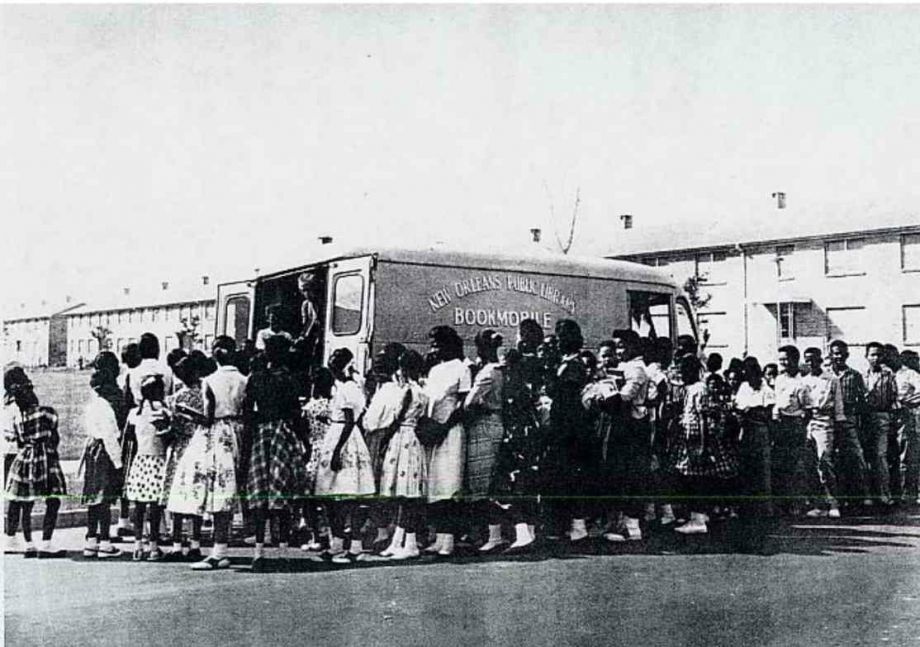

Attendees at a Neighborhood Story Project reading. Photo credit: NSP

Although Katrina was the most radical example of displacement in New Orleans’ history, it is far from the only one. The Desire Housing Project, where the Nine Times Social Aid and Pleasure Club originated, had been incrementally dismantled beginning in the mid-1990s and completely torn down by 2003, dispersing the club along with the thousands of other people who had lived there. Nine Times continued, in part, as a way of keeping its members’ and others from the Desire’s relationships intact. The tradition continued as people trickled back after the storm and was a bright spot in the social milieu of an otherwise devastated section of the city. The club’s creation through the interviews and storytelling of Coming Out the Door for the Ninth Ward functioned as a way for its members to solidify and celebrate their preexisting bonds with — and importance to — their community.

After Cornerstones, Himelstein and Breunlin returned to the nexus of the Neighborhood Story Project: publishing stories by high school students. They came back to John McDonogh High School, but the city, and the students’ relationship with it, had changed radically.

“People self-represent around neighborhoods all the time, like the Ninth Ward Hunters, the Seventh Ward Warriors, Nine Times — all of these things are calls out to neighborhoods,” says Breunlin. “And the kids at John Mac, that’s how they identified, which is why Abram originally had that idea. A decade ago, the students had very strong attachments to place, and it was a given that they could dive into that and feel connected to it. After the storm, though, when we did it at John Mac again, they remembered those connections, but they were gone for the most part.”

The new crop of books included a collaboration by two students who had grown up in different projects — one uptown and one downtown, a circumstance loaded with social significance in New Orleans — and whose families were trying to figure out what life would be like after public housing. Another, Aunt Alice vs. Bob Marley by Kareem Kennedy, tracks the author’s path from growing up in the St. Bernard Housing Project to refugee exile in Houston to returning to New Orleans and navigating the terrain to his enrollment in college.

“My writing coaches, Abram and Rachel, told me my writing was ‘too abstract,’ which meant I didn’t give enough detail, so I began to dig up tales from the hood,” Kennedy wrote. “Growing up, I knew I was poor and learned to be tough on the streets. Occasionally, I got in fights because kids made fun of my previous-year school uniforms and old Nikes. But the project used to be so alive, like a drummer beating his drum. I reminisced on hanging on the porch with my homies, ribbing, talking about chicks and smoking. Writing after Hurricane Katrina made me appreciate everything about my hood.”

To date, the Neighborhood Story Project has published 12 books, including an exhaustive catalog and oral history of the House of Dance and Feathers (2009), an ad-hoc museum in the Lower Ninth Ward dedicated to Mardi Gras Indians and other aspects of New Orleans’ African-American traditions, and the latest, Straight Outta Swampton: Life at the Intersection of Natural and Built Worlds in New Orleans (2013), a collection of stories by students at Lake Area High School. Currently, Himelstein is working on a book for the project that documents life on the “backside” of a New Orleans horse racetrack, collecting the stories of jockeys, groomers, trainers and others who work behind the scenes. And Breunlin is putting together a collection — Talk That Music Talk: Passing on Brass Band Music the Traditional Way, a collaboration with Bruce Sunpie Barnes at the New Orleans Jazz National Historical — that focuses on traditional brass bands and the ways in which music education has been passed down, primarily in neighborhoods — through schools, but also grassroots organizations and formal and informal mentorship networks. Now that New Orleans primary school district has become the first in the nation comprised entirely of charters, and the idea of a “neighborhood school” is a all but thing of the past, Breunlin’s book looks at the ways in which even the music has had to become more resilient in New Orleans since Katrina, another aspect of life the city’s native residents are struggling to keep alive.

Nathan C. Martin is a writer and editor in New Orleans. He is the author of the Wallpaper* City Guide to New Orleans and his writing has appeared in McSweeney’s, Oxford American, The Believer, VICE, and other places. He is the founder and editor of Room 220: New Orleans Book and Literary News as well as its related literary event series. From 2008 – 2010 he was associate publisher and web editor of Stop Smiling. He is currently at work on a book about Wyoming, his home state.