Every now and then, driving around his hometown of Shreveport, Louisiana, Steven Jackson gets out of his car at a stop sign or red light, hops out to the median or the side of the road and removes a sign advertising for payday loans, income tax advance loans, or sometimes even “holiday loans.”

Technically, all signage without city approval on city streets is illegal in Shreveport, but the signs keep popping up anyway. Taking them down is all in a day’s work protecting his constituents from predatory lenders, as Jackson is a commissioner for Caddo Parish, which contains Shreveport.

More formally, Jackson recently won unanimous approval from the parish commission to form a task force to address the issue of banking deserts in and around Shreveport. The top priority for the task force: finding a willing partner, either a bank or credit union, who could take some of Caddo Parish’s deposits and open branches inside banking deserts. Jackson estimates the county has around $144 million currently in cash and investments, some of which could be deposited into participating financial institutions.

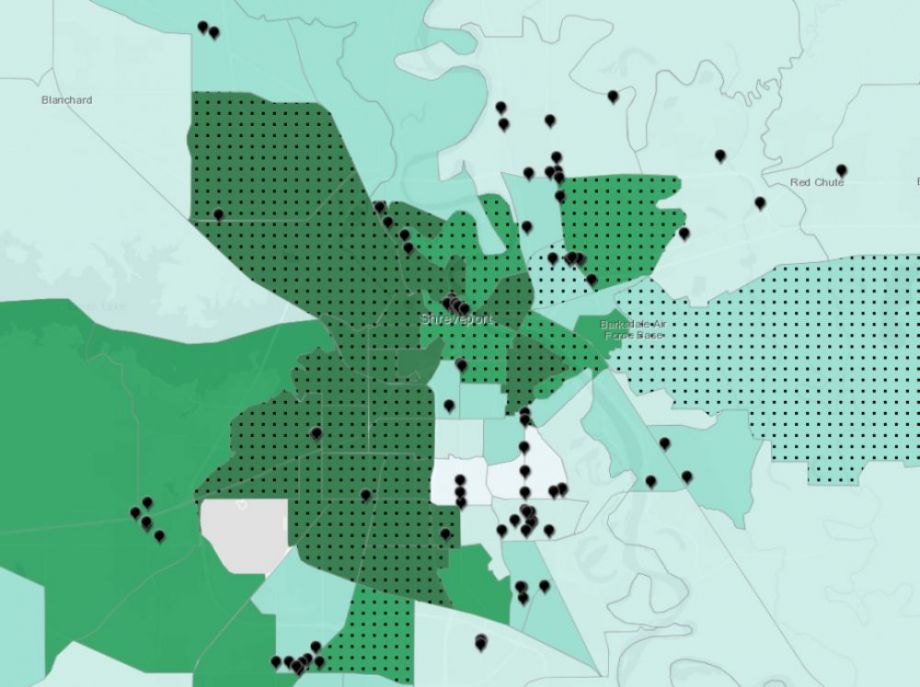

While banking deserts can have formal definitions, Jackson wants the task force to take a more locally responsive approach, like identifying neighborhoods where there may be a bank branch relatively nearby but also a large contingent of senior citizens or other households who do not have access to transportation.

It’s those same neighborhoods, in Jackson’s experience, that have also not coincidentally been targets for predatory lenders. “It creates a barrier for folks,” Jackson says. “If a person in the [predominantly black] MLK neighborhood had a new year’s resolution to open a savings account, they’d have to drive ten minutes to [a bank] branch, but you can easily find a payday lending place over there.”

Louisiana has more payday lender storefronts than McDonald’s locations. A scathing 2014 Louisiana state audit found that state regulators charged with regulating the payday lending industry were neglecting their jobs, instead uncovering an impressive range of tactics used to circumvent state regulations and maximize fees charged per customer.

There’s a long tradition of predatory lenders targeting the poor, and especially poor communities of color, in the U.S., a tradition that continues to this day. Caddo Parish is around 49 percent black, an estimated 22.4 percent of households live below the poverty line, and the median household income is around $40,000—below the U.S. median of around $55,000.

Jackson cut his teeth on the banking issue back when we was part of former Shreveport Mayor Cedric Glover’s administration, which established a Bank On Shreveport campaign that eventually grew into Bank On Northwest Louisiana. The initiative has provided financial counseling to help move thousands of people out of predatory debt traps, the kind that new rules from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau were supposed to curb. The Trump administration now plans to “revisit” those rules, which were to go into effect later this year.

Even if the new payday lending rules did go into effect, Jackson would still point to significant barriers because of the geographic distribution of branches. “We started noticing if Bank On is doing this work to get folks to get legitimate bank accounts, we still needed banks that were committed to them and convenient for them,” says Jackson.

Branches, while their role is certainly changing, still matter in Jackson’s view. “It’s the older population that you have to be sensitive to, especially when you’re talking about banking,” he says. “Also the working poor, individuals living paycheck to paycheck.”

Like many cities, the poorer or more minority an area is in Shreveport, the less likely there is a bank branch nearby. And even branches may not necessarily offer all the services most people would expect. One time, Jackson says he went to two different major national bank branches around the edges of Shreveport’s MLK neighborhood to make a cash payment on a credit card bill, and in both instances the branch staff told him they could not accept cash payments for credit card bills at their location.

The presence of trusted financial institutions in Shreveport also took a dramatic hit in April 2017 when federal regulators seized the historically black Shreveport Federal Credit Union, transferring its accounts and assets to the highest bidder—Red River Credit Union, based across the state line in Texas.

“Shreveport Federal Credit Union was literally built off the hard work, blood, sweat and sacrifice of city workers,” Jackson says. “Most were garbage workers, water and sewage workers who couldn’t get traditional loans for a car or house.”

The county hopes to use the state’s banking development districts program, which allows local governments to incentivize financial institutions to serve banking deserts by putting municipal deposits into new branches located in those areas. Banking development districts must be identified by the local government and approved by the state.

Other states have similar programs, like New York, where the state last summer created a new banking development district in the notoriously poor South Bronx. The state subsequently deposited $10 million into Spring Bank, headquartered in the South Bronx. Jackson says he took some inspiration from that program—although New York state law currently prohibits credit unions from taking municipal deposits, unlike in Louisiana.

The banking task force will also look comprehensively at other potential tools.

“We want to look at how banking has changed, maybe look at a mobile banking branch, just to see how can we provide access or how can access be created for traditional financing and banking,” Jackson says. “And there’s always an opportunity to rein in some of the payday lending through policies.”

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)