Let’s be honest: Bicyclists don’t always stop at four-way intersections when there’s no traffic coming on the cross street. I know it, you know it. But by the general law of the land in U.S. cities, stops are required, despite an inconvenience to cyclists and police expected to dole out citations for a common-sense behavior.

Now, after observing cyclists at six Chicago intersections, a group of researchers at DePaul University is recommending the city change how it approaches enforcement.

With 150 miles worth of protected bike lanes completed or underway in the past decade, and the second-largest bike-share in the country, Chicago is experiencing a boom in bike ridership that will likely continue for years to come. As more cyclists hit the streets, says Joseph Schwieterman, director of DePaul’s Chaddick Institute for Metropolitan Development, the city may need to make the rules more in line with reality. That could include legalizing what’s known as the “Idaho stop.”

Adopted in Idaho in 1982 out of frustration over minor cycling citations tying up the courts, the Idaho Stop Law allows cyclists to treat stop signs as yield signs, and traffic signals as stop signs. In other words, at stop signs, cyclists are expected to slow to a reasonable speed, yield to a car in the intersection, and cautiously proceed on through. At traffic signals, they must stop before entering traffic, yield to cars in the intersection, and then can proceed through a red light. In other words, it would be legal to do what cyclists already do.

“What we saw is that cyclists are practicing common sense when it comes to intersections. They want to maintain their momentum but they also want to practice behavior that is in the best interest of their safety,” says Jenna Caldwell, a DePaul researcher and avid cyclist.

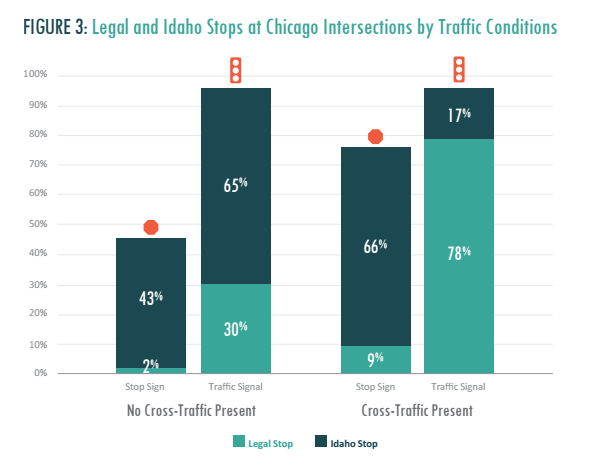

The study she co-authored with Schwieterman and others found that indeed, cyclists almost never make full stops at stop signs. When there was no cross traffic present, only 2 percent of cyclists observed came to a full stop. Far more, 43 percent, made an Idaho stop. The majority, 55 percent, just rolled right through.

At traffic signals with no cross traffic, 30 percent stopped and waited for a green light, while 65 percent made an Idaho stop. Only 5 percent took no precaution, cycling through the intersection without stopping or yielding. At both stop signs and traffic signals, cyclists exercised more caution when there was traffic on the cross street. The study notes that cyclists were more likely to make full or Idaho stops during rush hour, when more cars are on the road.

With ridership growing in Chicago and cities across the country, Schwieterman says it’s important to create “a culture of enforcement that’s in line with safe biking practices.” Enforcement is a key aspect of Vision Zero plans, which cities adopt with an aim to eliminate traffic deaths, but isn’t without controversy. Reviews of police records in Minneapolis and Tampa Bay showed, for example, that black cyclists were disproportionately ticketed overall.

Given how cyclists actually navigate intersections, Schwieterman says, it doesn’t make sense for cities to crack down using existing legislation. The study recommends two major changes: Allow the Idaho stop at four-way stop intersections, and lower fines or offer diversion programs to those cited for bike traffic violations.

According to the researchers, Chicago is already pretty lenient about ticketing cyclists. The vast majority of citations are issued for riding on the sidewalk, not for rolling through intersections. Given how common that behavior is, Schwieterman suggests it would be like ticketing someone for driving 1 mile over the speed limit — everyone does it. The study recommends Chicago implement diversion programs like those used in California, which allow anyone involved in a bicycle infraction not involving a motor vehicle to have their fine waived and avoid a violation on their record if they attend a safety class. In Chicago, the minimum fine for such violations is currently $50.

“Such a program would allow the City to pursue heightened enforcement of traffic regulations without incurring as sharp a backlash from the bicycling community,” the study reads. “Further, a diversion program and/or lowering fines for violations would make citations issued by law enforcement personnel less contentious, thereby enabling these officials to stop cyclists as more of a learning opportunity.”

After publishing the paper and seeing it reported on in the Chicago Tribune, Schwieterman made the mistake of reading the comment section. He says he was shocked by the vitriol it provoked in some.

“What we were surprised by was how much anger there was from motorists towards bicyclists,” he says. He’s gotten pushback from those who think allowing the Idaho stop means abandoning all laws for cyclists, that it sends a signal that cyclists are above the rules. For that reason, he thinks it would take a strong champion to get the Idaho stop adopted in Chicago.

Asked what she’d tell those who share that concern, Caldwell says, “I would tell them to read the law, the way that it’s written.”

The study also looked at the convenience and speed of biking in Chicago, compared to riding public transit or taking a trip with UberPool. Researchers made 45 trips between randomly selected points in the city using all three modes. Biking was faster than transit on 33 of 45 of those trips, and faster than UberPool on 21.

“To our surprise, longer trips [from a neighborhood] to downtown were often best by bike,” says Schwieterman. Cycling was consistently the fastest way to get between neighborhoods. Each of the randomly chosen routes used a bike lane or off-street trail at one point, and on 38 routes, more than half of the total mileage was on these types of trails.

“We wanted to show how bikes as a mode fits into the urban mix, both as a mode of convenience and as an active transportation option,” says Schwieterman. “We think the speed and convenience of bike travel has been underplayed or understated.”

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)