By population, New York is about four times the size of South Carolina, with roughly 20 million residents to South Carolina’s five million. But in 2016, about 3,000 more evictions were carried out in South Carolina than in New York, according to the Eviction Lab at Princeton University. In fact, South Carolina had almost as many evictions as California that year. Landlords filed more than 86,000 evictions in 2016, and completed 41,099 — meaning 41,099 tenants and tenants’ families were removed from their homes. At almost nine percent, the state’s eviction rate more than triples the national average, and is the highest in the country, according to the Eviction Lab.

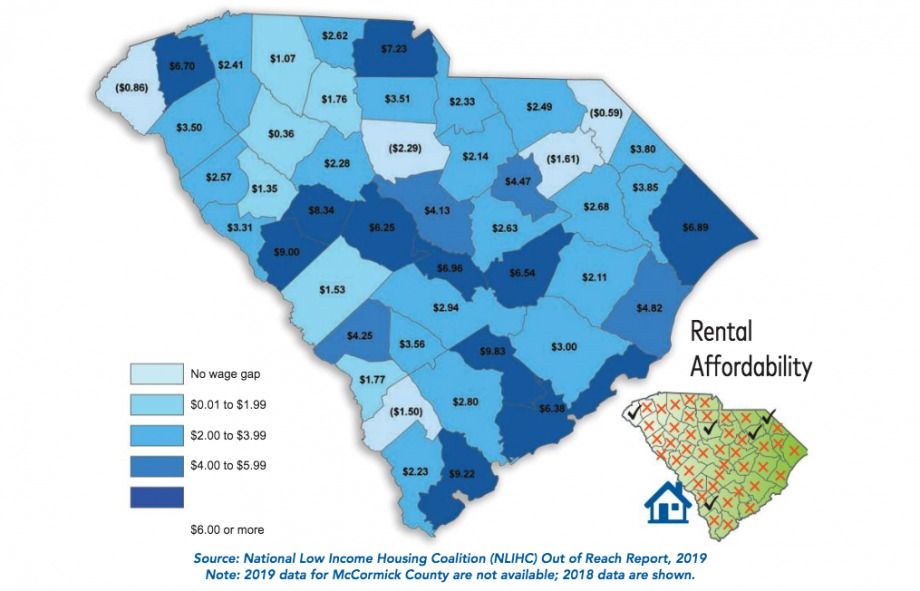

Eviction at that level causes widespread instability. And on top of that, according to a new report from the South Carolina State Housing Finance and Development Authority (SC Housing), South Carolinians are facing a host of other housing challenges: A third of renters pay more than they can afford for housing, a quarter of renters pay more than half of their income toward rent, there’s only one subsidized unit for every five low-income renters in the state, and a typical renter can’t afford a typical two-bedroom apartment in 41 of the state’s 46 counties. In all, the report says, “shelter poverty” — the inability to cover other essential living costs because housing costs too much — represents an $8 billion cost, borne by “public assistance, private charity, or personal deprivation.”

The report is the first time that SC Housing has completed a housing needs assessment for the state since 2002. Bryan Grady, chief research officer for SC Housing, who completed the report, previously worked as a research analyst at the Ohio Housing Finance Agency, where he completed similar research. He says that the group’s new CEO, Bonita Shropshire, wanted to expand its influence beyond its normal programs, which include helping to finance low-income housing projects with tax exempt bonds. Grady was hired at the beginning of the year, and has spent the time since then working on the research and meeting with affordable-housing developers and other stakeholder groups.

“[SC Housing] had a structure where we were good at administering the programs we were responsible for, but we were focused on that — kind of tunnel vision, keeping the trains running,” Grady says. “[Shropshire] signaled an interest in expanding, looking more broadly at our mission beyond just administering our programs, and how we can put heads in beds.”

The report finds that shelter poverty is widespread in rural counties, but the level of burden on individual families tends to be greater in urban areas, like Charleston. North Charleston, in fact, was identified as the worst housing market for evictions in the United States by the Eviction Lab. (One reason why eviction may be so prevalent in South Carolina is that it’s legally easy to file for an eviction there, and so landlords have come to treat eviction as a “first resort” when tenants are behind on rent, Grady says.) The SC Housing report includes a handful of suggestions for addressing statewide housing issues, throwing its support behind a bill that would create a state tax credit to bolster federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, and recommending that the state legislature consider allowing cities to adopt inclusionary zoning policies.

South Carolina State Representative Marvin Pendarvis, who represents parts of North Charleston, is a supporter of both measures. He says that while Charleston’s economy is driven by tourism, it has become much harder for people who work in hotels and restaurants to afford living in or near the city. But he doesn’t believe the problem is supply.

“There’s enough housing being built,” Pendarvis says. “We see a number of developments coming to the area, but because of the allure of the area, it’s costing so much. People are being driven out of areas they had been able to afford, and you’re seeing businesses being displaced.”

An inclusionary zoning policy, requiring some portion of affordable units in new development, would be beneficial in a city like Charleston, Pendarvis says. The enabling legislation he sponsored to let cities adopt inclusionary zoning policies didn’t get any traction the first time it was introduced, he says.

“Municipalities have great power to really do something about [affordable housing] in creative ways,” he says. “All we have to do is empower them to do so.”

The Housing Needs Assessment that SC Housing released is subtitled “Volume One.” Grady says that’s a hint that the group is planning to carry out more housing research and release reports more regularly. Future reports might look at individual cities, or issues specific to veterans, senior citizens, or people with disabilities, Grady says. Housing finance agencies have a specific role to play in terms of supporting housing projects, but they can also help build support for broader public action, he says.

And Pendarvis says the report helps draw focus to the issue, and he’s hoping that the state legislature will move take housing issues more seriously in the 2020 session.

“I’m hoping that this [report] will get the ball rolling, and that my colleagues will see that inaction on our part is only going to cost the state more and more money,” Pendarvis says.

This article is part of Backyard, a newsletter exploring scalable solutions to make housing fairer, more affordable and more environmentally sustainable. Subscribe to our weekly Backyard newsletter.

Jared Brey is Next City's housing correspondent, based in Philadelphia. He is a former staff writer at Philadelphia magazine and PlanPhilly, and his work has appeared in Columbia Journalism Review, Landscape Architecture Magazine, U.S. News & World Report, Philadelphia Weekly, and other publications.

Follow Jared .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)