If billionaire investor Chris Hansen ever successfully buys a basketball team for his home city of Seattle, the team might play in the first sports arena in the country to be warmed by sewage. Proposed plans for the arena include a “sewerthermal” system that would save the team money while keeping fans toasty warm in Seattle’s chilly climate.

Yes, when you start to explain that you’re keeping warm thanks to a sewer, eyebrows go up (sports fans are already saying, in jest, “We’re No. 2”). But sewage heat recovery, or the catchier “sewerthermal,” is a serious source of energy that cities around the world should be — and are — looking at.

Let’s say you have a building, or set of buildings, heated by radiators, which require steam. Making that steam requires heating a bunch of water to boiling. Because it’s easier to heat warm water than cold water, anything that can raise that starting temperature means cost savings.

One way to do this is to use a geothermal heat pump, which works by using the fairly constant temperature of the earth as a heat source. Another way is to tap into — figuratively — a city’s sewer lines.

Think of all the water that goes down the drain in a city: flushed toilets, yes, but also hot, soapy washing machine water, hot shower water, and more. And there’s so much of it that it stays a relatively constant temperature, at least in the trunk lines, even when you hit flush.

That makes the water an attractive heat source (or heat sink). Developers can use a closed-loop system (meaning, crucially, the water used in a boiler room never physically touches sewer water) to raise cold water to lukewarm or even warm, which saves end users a bundle.

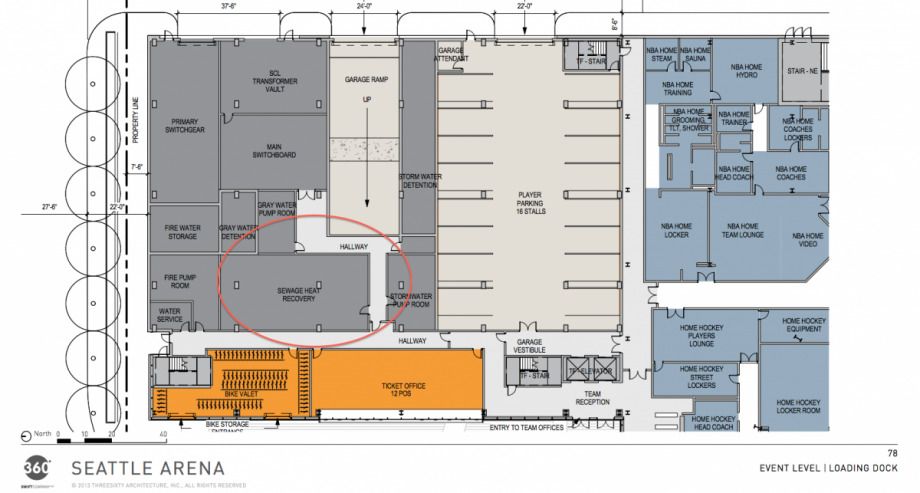

(Source: Threesixty Architecture)

In King County, Washington (Seattle is the county seat), when water officials held an informational meeting for developers who wanted to tap into this source, it was standing-room only, Jessie Israel, resource recovery manager at King County’s Wastewater Treatment Division, said. The temperature running through King’s sewers is a relatively toasty 60 degrees, even in the middle of winter. “I like to call it our most exciting renewable resource,” Israel said.

The technology paired with the much-older idea of a district heating system (one boiler that heats multiple buildings) has the potential to be a game-changer. Already, it’s in use elsewhere in the world: Vancouver’s Olympic Village, which was converted to condos after the 2010 games, was built with, and still uses, a sewage heat recovery system to generate 70 percent of its energy needs. Chicago’s wastewater treatment district has a modest heat recovery system on its own property that cut its heating and cooling costs by half, and in Europe, three cities are launching sewage heat recovery pilots as part of the Celsius City sustainability initiative.

But a sports arena launching such a system would be the most high-profile project in the States. “I think it’s brilliant,” said Scott Jenkins, chairman of the Green Sports Alliance, a national group dedicated to helping sports teams increase their sustainability footprints. “Why not? It’s energy, it’s free…it’s a neat way to kind of create an ecodistrict, and use a sports team as an anchor. With sports teams we have the ability to raise awareness and create interest around certain things,” like sustainability. And imagine the PR boost from building an arena “powered by sewage.”

Visibility isn’t the only reason that sewage heat recovery makes special sense for sports arenas and stadiums in urban areas. For one, only in cities do you have enough flow to build a large system, Jenkins said. Another reason, according to Israel, is that sports facilities tend to be located in more industrial areas, “where there’s massive sewer infrastructure.”

And because these buildings are intermittent users of heating and cooling, the alternatives are much less attractive. Either you spend money on building an enormous HVAC system, where its huge capacity goes unused most days out of the year, or you underbuild, which leads to sweaty fans. But with a district energy system (powered by sewage or no), neighboring urban buildings can share the heating and cooling capacity, using it the rest of the year. This is how Phoenix’s Chase Field, where the Diamondbacks play, works: the same chiller that cools the field for 82 home games a year cools 30 office buildings downtown when no game is in session.

The resource is more or less unlimited, since it’s gone untapped for so long. “Would King County consider letting somebody build a facility like this right outside the gate of our treatment plant? Probably not, because we need that heat to keep our digesters warm,” said Israel, “but…even half a mile outside, in an urban area, the degrees they’re pulling off are so minimal that it just heats right back up again.”

Interest is steadily rising in the States. “In the last year,” said Israel, “I’m asked for data monthly. Where our sewer lines are. What the flow is, what the temperature is in that area. I think that one stadium will do it, and several will follow their lead.”

Rachel Kaufman is Next City's senior editor, responsible for our daily journalism. She was a longtime Next City freelance writer and editor before coming on staff full-time. She has covered transportation, sustainability, science and tech. Her writing has appeared in Inc., National Geographic News, Scientific American and other outlets.

Follow Rachel .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)