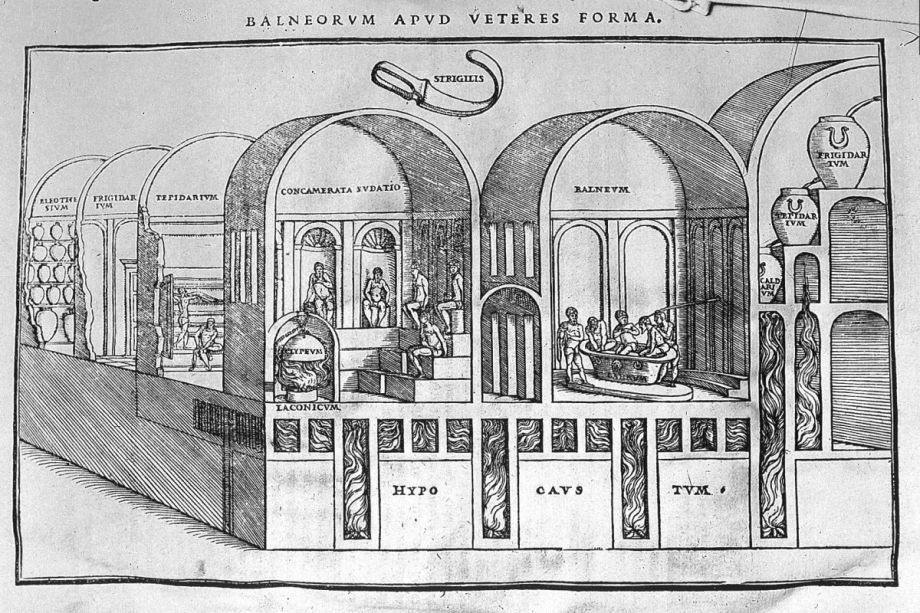

The cities of the Roman Empire were studded with great and salubrious public works: stadia and parks, aqueducts and fountains, latrines and sewers. By A.D. 400, Rome could count 11 magnificent imperial baths, decorated with mosaics, marble and sculpture, and more than 800 smaller spa complexes.

The ruins of those facilities have long impressed on us a view of Rome as a civilization of elevated health and hygiene.

The reality is that despite those amenities, the Romans were as riddled with parasites as their predecessors. Fish tapeworm, which appears to have been endemic to a fermented fish stew that traveled the empire in clay jars, was more widely found in Roman times than before. Poor sanitation parasites like roundworm were just as common as before.

Evidence of head lice and their eggs have been discovered on wooden combs from the Roman period in Israel; excavations of Roman-era Britain have turned up “large numbers of human fleas,” and what appears to be a bed bug.

“Despite their introducing sewers, public toilets, clean drinking water, we don’t see any drop in those parasites when you change from the Bronze Age and Iron Age to the Roman Empire,” says Piers Mitchell, an ancient disease researcher at Cambridge University. Mitchell’s report, published in Parasitology, tries to posit what might have gone wrong in Rome.

The colossal architecture of the baths is a more obvious relic of Roman society, but evidence of pathogens persists too. It’s just a little harder to see, since many diseases leave no trace on skeletons.

“Parasites have the advantage that the eggs of parasitic worms are pretty tough,” explains Mitchell. “The worms break down after death, but the eggs can survive for hundreds of years.” (That’s “survival” in an archaeological sense, not a biological one.)

But over the past century, and especially since the 1980s, paleopathology has developed rapidly. Mitchell has synthesized scores of reports on public health in the provinces of the empire before and during Roman rule. His is the first research to consider public health in the empire at large, and the conclusion muddles the perception of the Romans as pioneers in the field.

It also surprised Mitchell. “The Romans invented multiseat latrines. They instituted laws where towns were responsible for cleaning up feces and taking it out of town in carts. It was quite a substantial package of sanitation reforms.” The great cities of the West would not make parallel gains for nearly two millennia.

Generally, it seems the problem was not that the Romans had poorly designed their sewers or aqueducts. (Though water in the baths could probably have been changed more often.) Instead, alongside the chain of hygienic infrastructure there existed a parallel series of bad decisions that cumulatively worked to undermine expected health improvements.

The long-distance transport and subsequent consumption of that sun-fermented fish sauce, called garum, could have acted as a “vector” for the spread of fish tapeworm under Roman rule. Immediately after carting human waste from town (sanitary!), Romans were known to thrown it on the fields as fertilizer (unsanitary!). Human waste is a potent fertilizer — but if used right away, it also brings diseases directly to the crops.

How could the Romans be so prescient in some areas of public health and so neglectful in others? The answer, says Mitchell, is that they did not understand the sanitary benefits of their own improvements. Thanks to toilets and sewers, the streets didn’t stink. Bathing was a social experience, and a pleasure.

Their connection to good health, from a scientific perspective, was uncertain. Parasites like tapeworms, for example, were thought to be produced by the body when your four humors (blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm) were corrupted.

For today’s epidemiologists, one lesson of this story is that ingrained customs can counter the advances of sophisticated infrastructure.

For those who study our health in the future, our health might be viewed through our extensive medical records. But we too are leaving a kind of public health fingerprint in the earth. If Rome preserved the fossilized causes of illness, we are saving its cures: In 2008, two dozen American cities showed detectable levels of pharmaceuticals in their water supplies, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, antibiotics, beta blockers and tranquilizers.

None of those were found in large enough quantities to cause any harm. But they do furnish a geographically stamped record of a moment in public health — fodder for biological anthropologists of the post-apocalypse.

The Science of Cities column is made possible with the support of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Henry Grabar is a senior editor at Urban Omnibus, the magazine of The Architectural League of New York. His work has also appeared in Cultural Geographies, the Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal and elsewhere. You can read more of his writing here.

Follow Henry .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)