There’s a pervasive idea shared by some policymakers and the American public that low-income people are draining the government’s resources through what’s perceived as the nation’s “failed” public housing program.

In his 2013 book, New Deal Ruins, University of Minnesota professor Edward Goetz capsizes prevailing myths about urban housing policies, including how much governmental financial and managerial decisions failed public housing residents more than the other way around.

In a recent white paper presented to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy at a seminar co-sponsored by the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, Goetz and colleagues further confound commonly accepted notions of who benefits from America’s housing policies. Goetz says that social scientists and academics have known for years that white, affluent people benefit more from government subsidies than low-income Americans. But his team has created a brand-new way to represent this effect spatially in American cities.

Looking at the Minneapolis-St. Paul region, they found that in actual dollar amounts, roughly three times as many federal housing subsidies are going to concentrated areas of white affluence as are going to concentrated areas of nonwhite poverty. In our conversation below, Goetz explains their methodology, as well as why people might not be talking about the impact of affluence or race in public housing conversations.

Edward Goetz

What might people not understand about how housing subsidies work in rich neighborhoods?

There are two main ways that housing is subsidized in the U.S. The typical way of budget expenditures — every year Congress decides how much to spend on Section 8 or public housing — those are directed towards low-income people. The other way is through tax expenditures — tax breaks people receive which reduce their tax liability. There are ways to quantify the size of those savings for individuals, but there are also ways to calculate the total cost to the federal government. The largest tax break, by far, is the home mortgage interest deduction. The bottom line is, the lion’s share of those tax expenditures go to affluent people.

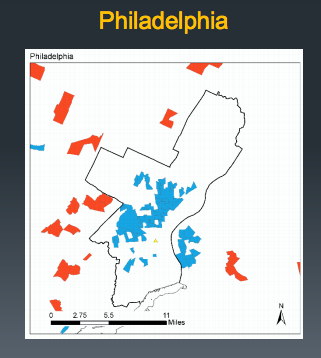

We developed a way of estimating where people who are getting these subsidies are living. The way we looked at the world is that we started with the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s [HUD] definition of what they call an RCAP, which is a racially concentrated area of poverty. An RCAP is a census tract that is more than 40 percent below poverty and more than 50 percent nonwhite. … What we did was try to define the polar opposite of an RCAP in what we called racially concentrated areas of affluence [RCAA]. We defined those places that were more than 90 percent white and had a median income that was at least equal to or more than four times the poverty rate. Both of those are arbitrary thresholds, but frankly, so are the two thresholds developed by HUD.

Your findings might be shocking for people, especially considering the push to reduce federal funding to public housing.

Right. This is clearly significant, because the other thing that distinguishes tax expenditures from budgetary expenditures is that they’re not reviewed every year. There isn’t a vote in Congress. These are tax breaks written into the tax code. They are generated every year and unless Congress takes up tax reform specifically, they just keep circling on and on.

Philadelphia’s RCAPs (blue) and RCAAs (red)

HUD has been throwing more and more weight behind the Rental Assistance Demonstration [RAD] project. How do you think it’s been implemented?

I think it’s too early to tell. I don’t know that we have enough of a track record. I can tell you that RAD, in some respects, is a good idea. If the problem is that we have decided we’re not going to allocate as much public money to affordable housing as is necessary, then we need to figure out ways of attracting private sector investment to it in order to keep these units operating. That, I think, is the spirit of RAD.

But the concern is obvious. Is this a way of accommodating a diminishing commitment to affordable housing? Furthermore, the concern of some is that the permanence of affordability may be in jeopardy, because public housing tended to be longer-term than the types of public-private partnerships that are sometimes used to create affordable housing.

Has there been any movement responding to your call in New Deal Ruins for there to be more monitoring of the racial impact of public housing policies?

No, not at all. I think it’s an uncomfortable conversation. I don’t think that policymakers want to talk about impacts in terms of race. They don’t want to talk about policy in terms of race and the distribution of benefits across races. I think in housing policy, there’s precedent for camouflaging all of this by talking about poverty instead of race. That may be done because the proponents of housing assistance feel they might have a better chance to get legislation passed if you talk about economic disadvantage instead of race.

We’ve got real issues with race in this country and I don’t know if there’s a great willingness on the part of elected officials to bring that issue front and center, especially in the way I recommended in the book, which was explicitly looking at the racial impacts of what we’re doing in the housing field. And of course, we talk about all of this in the backdrop of the looming Supreme Court decision on disparate impact. That’s going to be interesting to see what happens there.

Poverty deconcentration is used as the pretext to so many housing decisions in this country. Would there ever be housing policies guided by the deconcentration of wealth?

[Laughs] I don’t anticipate it ever in the future. We can highlight it, but I don’t for a minute think that anyone’s going to respond with a housing proposal.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Alexis Stephens was Next City’s 2014-2015 equitable cities fellow. She’s written about housing, pop culture, global music subcultures, and more for publications like Shelterforce, Rolling Stone, SPIN, and MTV Iggy. She has a B.A. in urban studies from Barnard College and an M.S. in historic preservation from the University of Pennsylvania.