With China’s growth slowing — a product of internal economic changes as well as the continued poor performance of the U.S. and Europe — the country’s government has decided to accelerate investments in its cities’ rapid transit networks as part of a larger transportation infrastructure program. About $127 billion (or 800 billion yuan) is to be directed over the next three to eight years to build 25 subways and elevated rail lines as a stimulus whose major benefit will be an increase in mobility for the rapidly urbanizing nation.

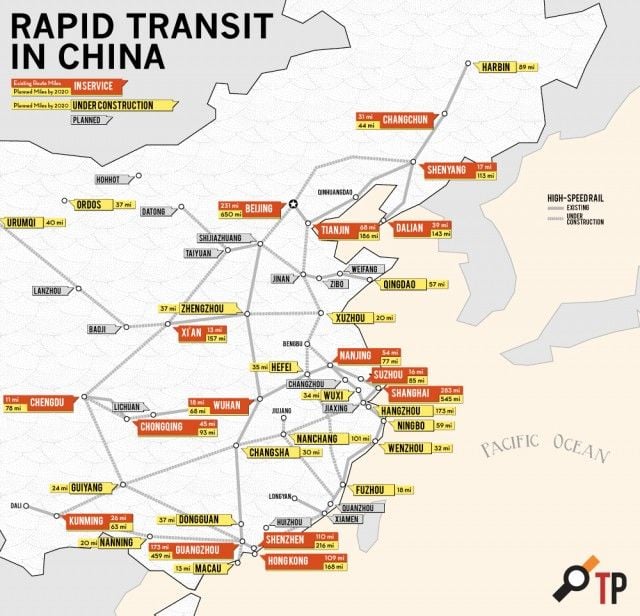

Though China’s high-speed rail network (now the largest in the world) has garnered most of the headlines when it comes to transportation there, the nation’s investments in urban rail have been just as dramatic and serve far more people on a daily basis. Its three largest metropolitan areas — Guangzhou, Shanghai and Beijing — feature the world’s fourth, fifth and sixth most-used transit systems, providing more than 5 million rides each day, more than similar networks in New York or Paris. Most of these cities’ lines have opened since 2000.

The high ridership, however, has not brought operational profitability to these systems, as Stephen Smith highlighted in an article this week. On Shanghai’s very extensive system, just one of 11 lines are able to cover their operations and maintenance costs — let alone pay back initial capital expenses used to build the lines. Meanwhile, construction costs have increased and cities paying for their completion have had to scale back their ambitions.

Yet the government does not accept the premise that a transit network that requires subsidies is necessarily a problem, at least based on its willingness this month to extend advance (and therefore heavily subsidized) loans to municipalities building transit lines. In general, the new national aid, which comes in the form of reduced borrowing costs, will allow for the fast-tracking of projects already in the pipeline, much as Los Angeles has hoped to do with its transit projects. On average, 42 percent of financing will be directed from local governments, with the rest financed by banks, all benefiting from the lower bond rates. Costs will be eventually covered through long-term tax revenue.

In addition to funding for Shanghai and Guangzhou to extend their networks, other cities such as Xiamen, Taiyuan, Shijiazhuang and Lanzhou have been offered national aid. By 2020, China will have 40 cities with metros extending 7,000 route kilometers, more than five times what exists in the United States today. The map below shows where new lines are being constructed, some with and some without help from the central government.

Chinese metro rail system development.

Is the Chinese investment in metros “worth” it? Unlike other countries, China has chosen to de-prioritize cheaper tramway or bus rapid transit systems (though certain BRTs, such as Guangzhou’s, have been very popular), despite the fact that the cost of building subways there has risen to almost the level experienced in developed countries. On the other hand, China’s cities are often larger and denser than their Western counterparts; of the cities planning to build metros, all have more than a million people in their respective regions and most more than three million. Munich, Germany, a city with a very extensive and well-used rapid transit system (and one that most Westerners would not question), only has about 2.6 million people in its metropolitan area.

Does the fact that new Chinese metro systems require operational subsidies pose a problem? It depends on your perspective. From a fiscal point of view, long-term operational aid will impose heavy burdens on local taxpayers, just as is true in U.S. and European cities. This is especially a problem because Chinese cities have intentionally set fares at very low levels (just 2 yuan a ride in Beijing), making it impossible to cover costs. Should China, with relatively low labor costs,* be in this situation?

It seems more likely that Chinese officials recognize that the metro investments, in addition to offering an important economic stimulus, provide positive externalities that outweigh the subsidies that will be required to maintain the systems. By setting fares low, the metro lines are able to attract higher ridership and passengers from across the income spectrum. Even in the densest, most-packed city centers, metro systems allow largely congestion-free mobility that is able to handle far more people and provide faster service than equivalent tramway or BRT programs. There is a reason these projects have proven so popular among China’s citizens. The transportation benefits they offer certainly contribute to economic growth in the center of the cities they serve and likely limit the suburbanization of jobs.

In combination with efforts in cities like Shanghai to restrict automobile use through license plate restrictions, spending on new metros will encourage a huge percentage of the population to remain public transit users, rather than switch to private cars even as incomes increase. Developing countries that have invested less in their rapid transit networks (Bangkok’s 35 miles of lines serving a metropolitan area of 12 million inhabitants comes to mind) have failed their populations by offering them little alternative to automobile use, and thus encouraged pollution and road congestion — two problems that already plague China’s cities.

Of course, China’s investment in new transit has not meant a shutdown on road capacity projects. The National Development and Reform Commission (which also approved the metro plans) announced last week that a large amount of funding will also be directed to new highways, leading to the eventual construction of 1,254 miles of new roads.

* On the other hand, the country’s per capita growth has been sensational; it is rapidly adopting the norms of wealthier countries.

Yonah Freemark is a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center at the Urban Institute, where he is the research director of the Land Use Lab at Urban. His research focuses on the intersection of land use, affordable housing, transportation, and governance.