In a Minneapolis neighborhood whose history has swung between neglect and destructive public projects, a proposed greenway is stirring up fierce passions, pro and con. In over four years’ worth of public engagement surveys, a majority of north Minneapolis residents said they’d support some kind of low-traffic or no-traffic bicycle and pedestrian corridor. But some residents still feel the project is being foisted upon them. Now the neighborhood is engaged in the ultimate test: A 5-block pilot of the proposed 37-block, 3.5-mile route was unveiled earlier this summer and will remain in place for an entire year.

“There are folks on the block that hate it, don’t like it, are upset that it was done. There are people on the block who think it’s amazing,” says Russ Adams, executive director of the Alliance for Metropolitan Stability, a coalition of organizations advocating for racial, economic and environmental equity in Minneapolis. The group was brought on by the city to assist in public outreach regarding the greenway in 2014.

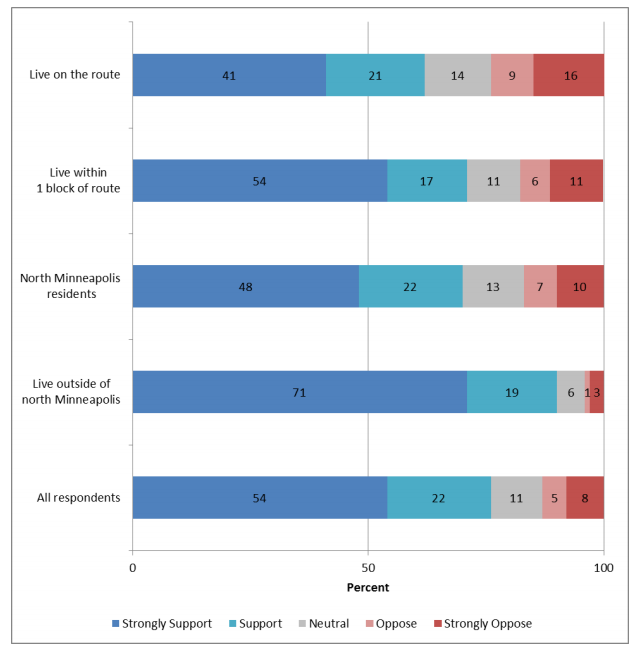

2014 survey results show support for the project, with the highest level of discontent on the affected route itself (Credit: Minneapolis Department of Health)

The impetus for a Northside Greenway was the desire for a better north-south bicycling route, modeled after a successful east-west Midtown Greenway. That 5.5-mile route took advantage of a former rail corridor, however. The Northside Greenway proposes removing traffic and street parking on some or all of 37 residential blocks, in a neighborhood accustomed to either being overlooked or steamrolled.

Alexis Pennie, a north Minneapolis resident and community advocate, says his neighborhood, which is historically black, has long been labeled the “poor side” of the city. Highway 55 severs the neighborhood, and a reconstruction project isn’t slated to improve that.“It’s kind of a systematic racial disparity that’s been ongoing for many, many years,” says Pennie. “Basically the rest of the city was getting improved and north Minneapolis was getting left behind.”

So Pennie understands why people might be suspicious of a massive new project, especially one so close to home, threatening to take away some street parking and have an uncertain impact on safety and property values. But Pennie also sees the project as a huge boon to the neighborhood.

“That’s the sad part. This part of the city could really benefit from amenities that would encourage people being active and doing activities in their communities, as well as access to healthy foods,” he says. The greenway could improve active transportation routes to commercial corridors, and may include community gardens. Community feedback also showed that residents liked the idea of additional green space, places to gather and play space for kids, and hoped a project like this would increase economic development.

Three possible designs are on the table for the as yet unfunded proposal. All three are being tested in the pilot. The northernmost block got the full linear greenway treatment: It’s completely closed to cars (except emergency vehicles) using bollards. The next three blocks to the south received a low-key bike boulevard treatment. Stencils indicate it’s a bike route, and bumpouts have been used to create gathering spaces where some street parking once was. The southernmost block in the test is “half-and-half”: street parking and one-way traffic is maintained on one side of the road, active transportation on the other.

The five blocks in the pilot were chosen because residents there showed strong support during the four years of surveys and feedback. “You can’t move a project like this without going out and talking to the neighbors,” says Adams. “It’s the type of project where you can never do too much community outreach.”

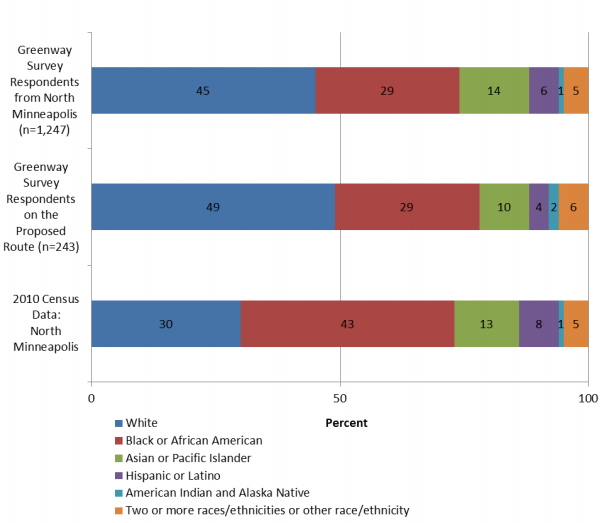

That seemed to be the city’s philosophy too. In 2012 and 2013, the city started gathering resident feedback via traditional methods, by online survey, email and phone, and at public meetings. Sarah Stewart of the health department, which is leading the greenway efforts, says they weren’t collecting race or ethnicity data in this round of engagement, but from the overwhelmingly white town meetings and the overrepresentation of homeowners in survey respondents, it quickly became clear that not all voices were being heard.

“This is a really, really diverse community, and we weren’t engaging all sectors of it,” she says.

2014 survey results after broadening outreach (Credit: Minneapolis Department of Health)

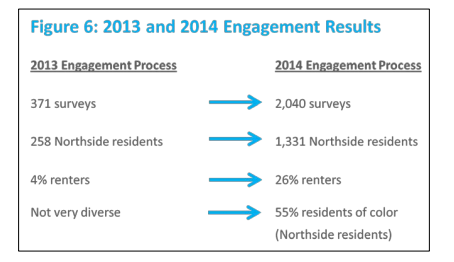

So in 2014 and 2015, the city tried a new tactic. The Alliance for Metropolitan Stability was hired, and launched a program of microgranting to pay neighborhood organization staff and community leaders to go out and talk to people. Adams says cities can’t expect to just enlist the help of overworked neighborhood groups without some incentive.

About 30 different organizations received $115,000 in microgrants to knock on doors, host events and gather feedback. Of those groups, 28 were led by and representative of people of color, and they were all based in north Minneapolis. Another $25,000 was paid directly to community leaders to talk to people about what they thought.

Responses came in from more sectors of the community, including more people of color, and more renters. But the ambivalence remained. Adams and Pennie admit there are plenty of valid critiques. Everyone on the 37-block route has alleyway access, but not everyone’s garage or backyard is suited for parking. There are questions about whether lighting in alleyways will be improved to increase safety if more people are using them, and whether they’ll get better plowing in the winter.

(Credit: Minneapolis Department of Health)

In some cases, the debate has gotten pretty brutal. People are concerned about strangers hanging out in their yards, and about disabled people having the access they need. (The southernmost block of the pilot was already tweaked to the half-and-half design from a full greenway to accommodate the needs of a disabled resident.) An anti-greenway group has accused the project of racism, sexism, classism and ableism.

“One of the better critiques is, kids along some of these blocks are reclaiming the streets, but what kind of lesson are you showing the youngest kids, that it’s safe to play in the streets?” says Adams. “What happens when you remove the demo project? What have you conditioned them to expect?”

Pennie has questions of his own: How will renters be protected from displacement if property values increase? If the project goes forward, will construction contracts go to local companies? “When you start exploring a concept like this, people get really creative about what kind of community benefits they want to see,” Adams says.

He also points to an example in South Minneapolis that could lead the way. Residents on two blocks there got together and agreed to remove traffic and parking to create a pedestrian promenade. Adams says, why not do it block by block in north Minneapolis too? If one block wants to go for the full greenway, and the next just wants a bike boulevard stencil, and the next wants the half-and-half, he thinks a route could still be stitched together.

“You work where you have the largest support and most open-mindedness,” he says. “You let them see how it’s working out on the blocks that went full-fledge. After a few years, you can probably pick up more support.”

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)