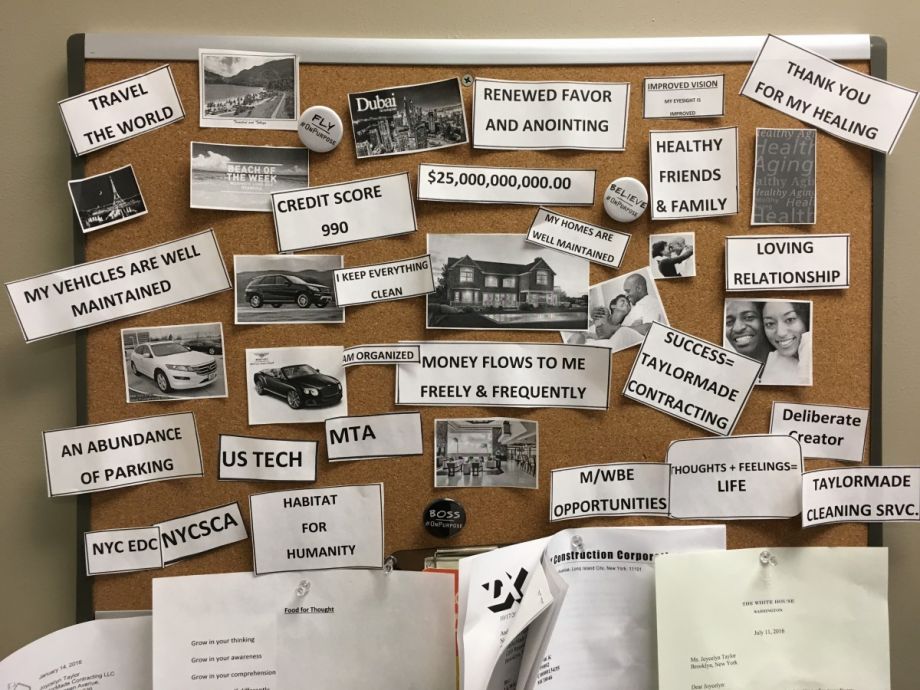

Inside Joycelyn Taylor’s one-room office in the Canarsie section of Brooklyn, there’s a bulletin board that reminds her daily of the goals she has for her business and what’s going to help her achieve them. The bottom line: She intends for her company, TaylorMade Contracting, to one day be earning $25 billion in revenues. A new contract financing loan fund from the city may help her get there.

“But I’m not thinking about it from the financial aspect,” says Taylor, who grew up in Pink Houses, a public housing complex not far from where she works today. “Think about the lives you’re going to be able to impact. When you are able to have access to those kinds of clients. The students you’re building schools for. The workers, the quality of life you’ll allow them to be able to have. A lot of people, and I get it, everybody works toward having goals, having nice things, this, that and whatever. But we can’t take any of that with us.”

She and co-owner Larry Alexander built the company amid the wreckage left behind by Hurricane Sandy. The storm hit New York City on October 29, 2012, and by November 15, Taylor and Alexander had registered their new business. By December they had their first contract to rehab a storm-ravaged basement on Long Island. The partners were a perfect match, with Alexander’s decades of experience in home building and home improvement, and Taylor’s decades of experience in real estate and managing business operations — including 15 years at a New York state housing office.

They were able to use their life savings for some startup capital, but that financing wasn’t their first choice.

Joycelyn Taylor (Credit: NYC Small Business Services)

“It was interesting,” Taylor says of trying to getting to get a loan as a startup. “When you go out and you want to get a loan for a car or something else, that’s very easy to get. But when you want to get a loan for your business, it’s very, very challenging.”

Even after starting to earn revenue and posting multiple years of successful cash flow, Taylor says they’ve tried and been denied at least twice in requesting a line of credit from the large commercial bank that handles their business. That presents a major obstacle when trying to go for larger clients and projects.

“That really stunts the growth of a company because they can only do one job at a time,” says Gregg Bishop, commissioner of NYC’s Department of Small Business Services (SBS). “If you have some cushion where you can start one job, work on that job and bid on another and then you have multiple jobs happening, you’re expanding your ability to grow because you’re hiring additional people. That cash flow becomes more robust and you become a healthier company.”

Some of the challenges are historical, Bishop notes. “For a lot of MWBEs [minority- and women-owned business enterprises], it may be the first time they’re starting a business, they may not have the collateral necessary,” he says. “Other times it’s just the very nature of being a small business and not necessarily having that cushion to expand rapidly.”

For most white entrepreneurs starting out, the reality is friends and family or business partners’ personal bank accounts provide enough liquidity to put a new business on a higher-growth trajectory. The latest available statistics show median wealth is $144,200 for white households compared with $11,200 for black households in the U.S.

The city has designed its new $10 million contract financing loan fund with the specific needs of MWBE firms in mind. Eligible borrowers must be for-profit, and have won a contract, are pursuing a contract, or have position as a subcontractor on a city-funded project. MWBEs may come from any industry as long as the city is ultimately buying their product or service. The contract serves as collateral for the loan. Crucially, MWBEs can also apply for a pre-qualified approval letter that they can submit as part of their bid package in order to demonstrate financial capability of fulfilling the contract.

“We don’t want MWBEs to wait until they get a contract,” says Bishop. “If they have any inclination of bidding, you should apply now so that we can pre-qualify you.”

TaylorMade was one of the first to access the contract financing loan fund earlier this year. The firm won a contract to do some remodeling at the main offices of the NYC Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC), the city’s quasi-public economic development authority. In rapid fashion, they got a $27,000 loan through BOC Capital Corporation, one of the three participating lenders in the program. They purchased materials and equipment, commenced work and didn’t have to worry about paying workers on time. They had 10 days to complete the job, but Taylor says they did it in eight.Even better, thanks to the loan fund setup, Taylor didn’t have to worry about making payments on the contract financing loan until NYCEDC paid TaylorMade. “It takes a lot of the burden off of the contractor,” Taylor explains. (Technically, under the program, the agency that needs the work done pays the participating lender.)

Participating lenders draw from the $10 million in the loan fund as needed and keep the repaid funds in separate, revolving accounts designated for contract financing. SBS has also contracted with the lenders to provide technical assistance to each MWBE in the program as needed to support successful completion of work under what will be for many MWBEs their first prime contracts with the city.

For MWBE subcontractors, the contract financing loan fund can ease the burden of chasing after prime contractors, some of whom are notorious for stiffing subcontractors (like a certain real estate developer-turned-president who continues to stiff subcontractors even while in office). The contract financing loan fund ensures subcontractors can get at least part of their payment upfront, and not have to worry about repaying that loan until the prime contractor makes a payment.

The maximum loan size is $500,000, and the interest rate is 3 percent. It’s a huge step up from the city’s earlier contract financing program, which merely connected businesses to existing lenders (such as BOC Capital Corporation) without putting any of the city’s own capital behind the loans. Under the earlier program, the maximum loan size was $150,000. “That’s not necessarily enough to help you,” admits Bishop.

With the city’s $10 million serving as loan principal, SBS is able to dictate terms, like $500,000 maximum loan amount, no credit score minimum, and also the friendly repayment scheme. The $10 million is a one-time infusion of city taxpayer dollars.

As of Tuesday, the contract financing loan fund had facilitated four loans totaling $272,000, including TaylorMade’s loan. The loans are supporting construction and architecture projects with the Department of Sanitation, Department of Design and Construction, and NYCEDC.

“We’re chipping away at all the barriers we have heard about from MWBEs,” says Bishop, who ascended to his current position in late 2015. In January 2016, at one of his first public events as commissioner, contract financing was a major sticking point. Taylor, as co-founder of the NYC MWBE Alliance, has also frequently brought up contract financing among other issues when meeting with various city officials. Such discussions have gained even more importance for the city after Mayor Bill de Blasio set a goal of awarding 30 percent of public procurement contracts to MWBEs by 2021.

It’s a lofty goal, especially considering only 4.8 percent of the NYC’s procurement of goods and services went to MWBEs in 2016, a decrease from 5.3 percent in fiscal year 2015, according to the annual Making the Grade Report from NYC Comptroller Scott Stringer. The scant figure is particularly troubling when you consider that MWBEs comprise just over half of all firms in New York City, with 539,447 minority-owned firms and 413,899 women-owned firms. Even while there are a record high of 4,500-plus MWBEs currently certified by SBS, the comptroller found only 994 received city spending on goods or services in FY16.

TaylorMade has been one of the fortunate few, landing its first city contract last year with the city School Construction Authority.

“I always remind people,” Bishop says, “[the MWBE] program was dormant for 20 years. [Former NYC Mayor] David Dinkins had initially created the MWBE program, then [former NYC Mayor] Rudy Giuliani ran his campaign on eliminating the program.”

Only around 700 MWBEs were certified by the city at the time Bishop first came to SBS in 2008 (MWBE firms must recertify every five years). It’s been nearly a decade of rebuilding the program, and earning the trust from MWBEs to convince them it would be worth their time to register and maintain updated information. “Those were some very difficult conversations,” Bishop says.

SBS also recently invested resources to establish partnerships in each borough to clean up and maintain accurate MWBE data, including contact information and appropriate industry coding. Updated information ensures MWBEs get notified by the city’s automated purchasing system when they are eligible for an opportunity. According to Bishop, roughly 94 percent of city contracts are for less than $100,000. By law the city does not have to advertise those purchases to the general public.

“The bulk of our purchasing is not advertised. The only way you could actually learn about those opportunities, especially with our automated system for between $20,000 and $100,000, is by having the right codes,” Bishop says.

In addition to the contract financing loan fund and improved MWBE data management, the city is planning to break up some larger contracts into smaller, more bite-size contracts that MWBEs are more ready to pursue. It’s a change that Taylor was on hand to celebrate last week at an NYCEDC event at City Hall.

Ultimately, Bishop draws connections between faster-growing MWBEs and larger goals beyond jobs or wealth, given where MWBEs tend to be located in the city and how their owners tend to employ others who look like them or live near where they live. For example, some research suggests that more successful black-owned businesses tend to pull black youth away from violent crime.

“At the end of the day, having programs that help small businesses grow has other effects, including, dare I say, crime reduction, because people are working,” he says. “I would say there is a little bit of cause and effect, and it would need some research and some years to see that correlation, but I’m a strong believer that as companies grow they create opportunities for individuals in the local community to get decent-paying jobs.”

Editor’s Note: This article has been updated to correct details about the terms of and qualifications for the contract financing loan fund.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)