For Karla Bruce, data can be a cultural force. Data can start conversations that would not have started any other way, or it can move conversations in directions that weren’t possible without it.

As chief equity officer for Fairfax County, Virginia, Bruce and her small team use data to start and move conversations that have to do with re-shaping county government to stop contributing to outcomes that favor white households above all others. In Bruce’s mind, without that internal cultural work, any reforms or policy changes instituted by the county board of supervisors or the country executive can be undermined when it comes time to implement them at the department or agency level.

“To me it’s not just about reform, it’s having the internal cultural context and awareness to understand why those reforms are necessary,” says Bruce. “That matters when you talk about how policy, whether what’s on paper ends up being supported or not.”

To help start and move its conversation around racial equity back in 2015, Fairfax County worked with the national research and advocacy organization PolicyLink to produce an “equitable growth profile,” which eventually led to the OneFairfax policy for equity and Bruce’s hiring in 2018 as the county’s first chief equity officer.

“I would hope we could someday be at a stage where we don’t need a chief equity officer, but there are competing priorities and ongoing pressures in government, so you need somebody who is always going to center equity, always looking at who benefits and who is harmed,” says Bruce. “Equity should be a part of everybody’s work, but making that happen, developing standards of practice around that, is a body of work in itself.”

On a national scale, PolicyLink recently unveiled the Racial Equity Index, a tool intended to help more local and state governments start conversations around racial equity. Produced in partnership with the University of Southern California’s Equity Research Initiative (formerly the Program for Environmental and Regional Equity), the index combines nine specific data points into a single score, ranking the most populous 100 cities and 150 metropolitan regions and all 50 states. Work on the index started about three years ago, so the timing of the racial equity index coming out now is a fortunate (or unfortunate) coincidence.

“This moment feels different in terms of more people coming to recognize the reality of structural racism in our country and being activated to do something about it,” says Sarah Treuhaft, vice president for research at PolicyLink. “I think there is a real potential for deep change that has been activated by George Floyd’s murder and other recent police killings.”

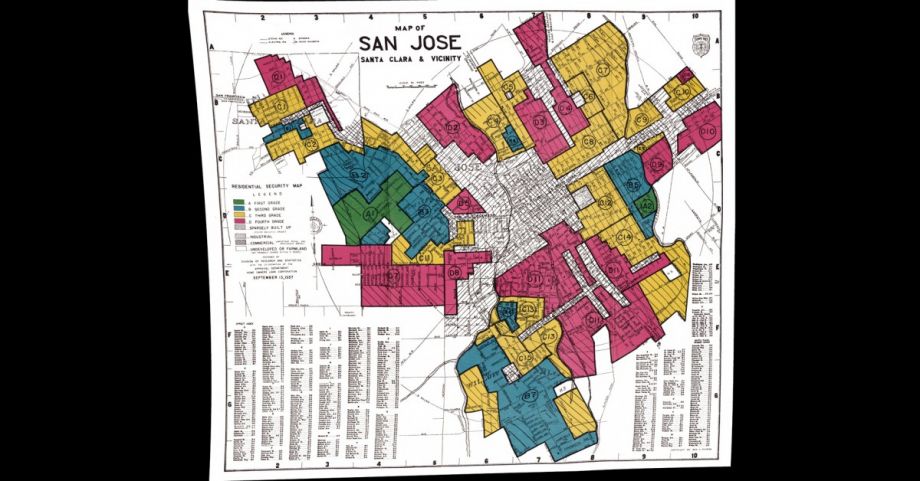

According to the Racial Equity Index — and this should surprise no one — every community it measures is hindered by systematic racial inequities. Even in the best-performing places on the index, San Jose, “there are significant and preventable racial inequities.” The index also reveals that robust economic growth, in terms of job creation and economic output, by itself does not lead to more racially equitable results.

The Twin Cities, for instance, ranked sixth in terms of overall economic performance as a region, but 149th in terms of inclusion — meaning its economic growth did not reach all racial and ethnic groups equally. That combined performance ranks the Twin Cities region at 144th out of 150 on the overall Racial Equity Index. The San Jose metro region topped the rankings, while the McAllen metro area in Texas ranked last. New York City was near the bottom, 127th; the Los Angeles metro area was 109th and the Chicago metro was 87th.

The data used to compose the new Racial Equity Index isn’t new. It has all been available in one place since the 2014 launch of the National Equity Atlas, an ongoing partnership of PolicyLink and the USC Equity Research Initiative. The atlas compiles 30 indicators for the 150 largest metropolitan areas across the United States.

It was under the auspices of the National Equity Atlas partnership that PolicyLink worked with Fairfax County on its equitable growth profile back in 2015. The realities contained within Fairfax County’s equitable growth profile aren’t new either, especially to the communities who have lived experiences of racial inequity themselves. But Bruce says it was valuable to have those experiences validated in data presented by public officials.

Having user-friendly data made for a more productive discussion of issues like the fact that white workers with only a high school diploma have a lower unemployment rate than Black workers with a bachelor’s degree in Fairfax County.

“People were just happy to talk about these issues with their local government in ways that didn’t place fault on individuals,” says Bruce. “At a policy level, the government had information to better understand its role in sustaining these outcomes.”

But not every city or region may be where Fairfax County was in 2015 when it commissioned PolicyLink to compile its equitable growth profile. The intent behind the new racial equity index is to meet more cities and regions where they are in terms of their racial equity conversations.

“Since we’ve released the [National Equity Atlas], over time there is a growing recognition of structural racism and attention being paid to racial inequities,” says Treuhaft. “Users of the atlas told us they would like a more comprehensive picture of the state of equity in their communities.”

An index is tricky to compose. Choosing what to include and how to weight data can oversimplify or leave out important connections. Treuhaft says they also wanted to make sure the index didn’t incorporate measures that were redundant or not as precise.

For instance, Treuhaft explains early versions of the index included school poverty as well as neighborhood poverty, but the final index left out neighborhood poverty because even in a lower poverty neighborhood, the wealthier children may go to private school in another part of the city and it’s the concentration of low-income, often Black or Latino children in public schools that really shapes disparate outcomes later.

Leaving out neighborhood poverty made room to include air pollution, which is well-documented to be higher in Black and Latino neighborhoods.

“No one index is ever going to incorporate everything,” says Treuhaft. “We do not have criminal justice data in the National Equity Atlas because there’s not a good national source for that information.”

Whether it’s just the racial equity index or a full-blown equitable growth profile like Fairfax County, it also takes work after seeing the data to keep the conversation ongoing. With the authority of the county executive’s office behind her, Bruce tasked each county department or agency to designate an equity lead, whom her office could train “on the foundational principles of advancing equity.”

Working with Bruce’s team, each equity lead created an equity impact plan for their department, finalized in December 2019. Bruce was planning for each lead to submit an annual report on progress around those plans this coming December. “Everyone was just at the operationalizing phase as the pandemic hit,” says Bruce.

The need to focus on pandemic response efforts may delay the annual reporting process, but actual progress on racial equity may end up going further than originally anticipated. Just as the racially disparate impact of the pandemic became clear, the killing of George Floyd put an even brighter spotlight on the realities of racial inequity, including in Fairfax County. Bruce has found her colleagues are suddenly more willing to make changes based on racial equity data.

“It’s been really interesting, there were concepts and terminology that I didn’t think would be palatable, I didn’t think people would be ready for until the uprisings around George Floyd’s death,” says Bruce.

Fairfax County hasn’t come very far in terms of moving the needle on racial equity, but that’s par for the course. Bruce’s colleagues — not to mention others at all levels of government across the country — have to work against 400 years’ of racial inequity in policymaking. Early wins may not seem like they’ll move the needle very much toward racial equity. But Bruce sees her job as part strategist, part historian, and even part cheerleader — making sure even the earliest and smallest wins get celebrated and acknowledged within the larger context of working against that history.

“I hate the concept of low-hanging fruit and quick wins, but I do value ways to keep people moving forward,” says Bruce. “People by nature are focused on being transactional or task-oriented and want to keep moving onto the next issue but those things have to add up, they have to be part of a broader strategy.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)