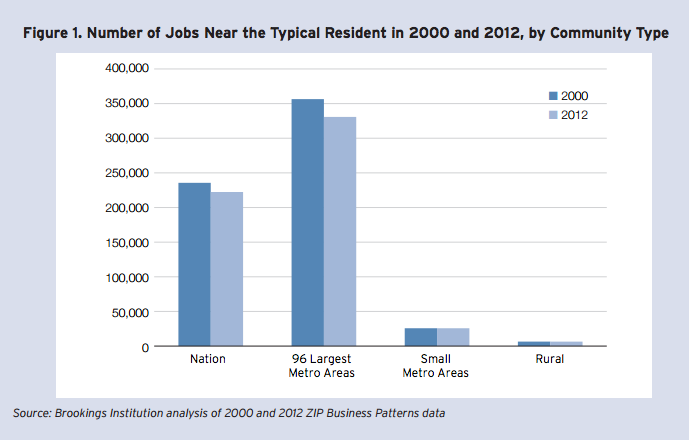

If you’ve been complaining about how hard it is to find a job in your neighborhood or how far you travel each day to get to work, here’s a little data to back up your concerns: Between 2000 and 2012, the number of jobs within the typical commute distance for residents in a major metro area fell by 7 percent.

Last week, the Brookings Institution released a new study of declining job density called, “The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America.” As its name implies, the study looked at the impact of decreasing job density within a typical commute in America’s largest metro regions. It paints a grim picture of an increasingly suburbanized poverty isolated from jobs, services and the transportation needed to access them.

“The outward shift of both people and jobs in the 2000s changed their proximity to each other, and often not for the better,” write report authors Elizabeth Kneebone and Natalie Holmes.

Brookings compiled a national database of demographic and employment data from 2000 to 2012 for every Census tract in the U.S. in order to determine how many jobs there are in each tract (job proximity), how that proximity changed over 10 years, and how that change affected different types of communities, especially in the country’s largest 96 metropolitan areas. The study counted the number of jobs within a “typical” commute — the definition of which varies by region, from 4.7 miles in Stockton, California, to 12.8 miles in Atlanta — to determine the density of each metro’s job proximity.

(From the Brookings Institution’s “The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America”)

In the past, similar studies focused on the implications of wealth and jobs leaving the city for the suburbs. But with increasing numbers of minority and low-income populations living in the suburbs, the report says old ways of thinking about and assisting disadvantaged communities may no longer be sufficient.

At its simplest, job proximity impacts the likelihood of employment and is important for quality of life. It also has equity implications. If high-income workers can’t live close to jobs, they can often afford to commute by car or live near viable transit options. But the Brookings study explains, “for poor residents, living closer to jobs increases the likelihood of working and leaving welfare … because they tend to be more constrained by the cost of housing and commuting.”

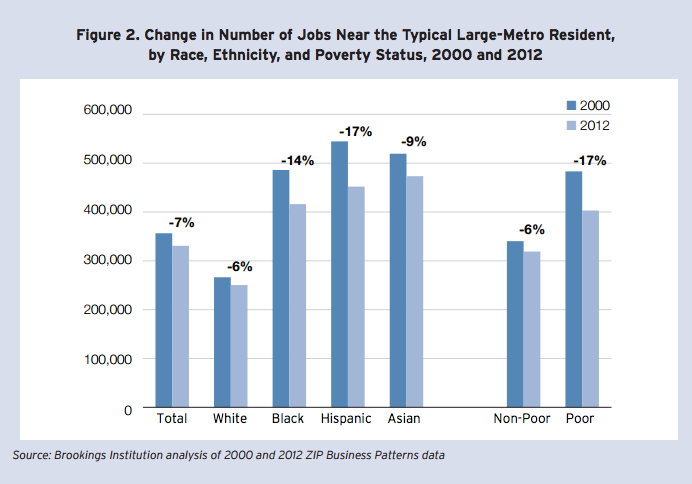

Job proximity fell by 7 percent in major metropolitan areas from 2000 to 2012, but the impact was, of course, not even across neighborhoods. The study found that, the average number of jobs near Hispanic and black residents dropped 17 and 14 percent, respectively, versus 6 percent for white residents. Job proximity dropped 17 percent for poor residents versus 6 percent for non-poor residents.

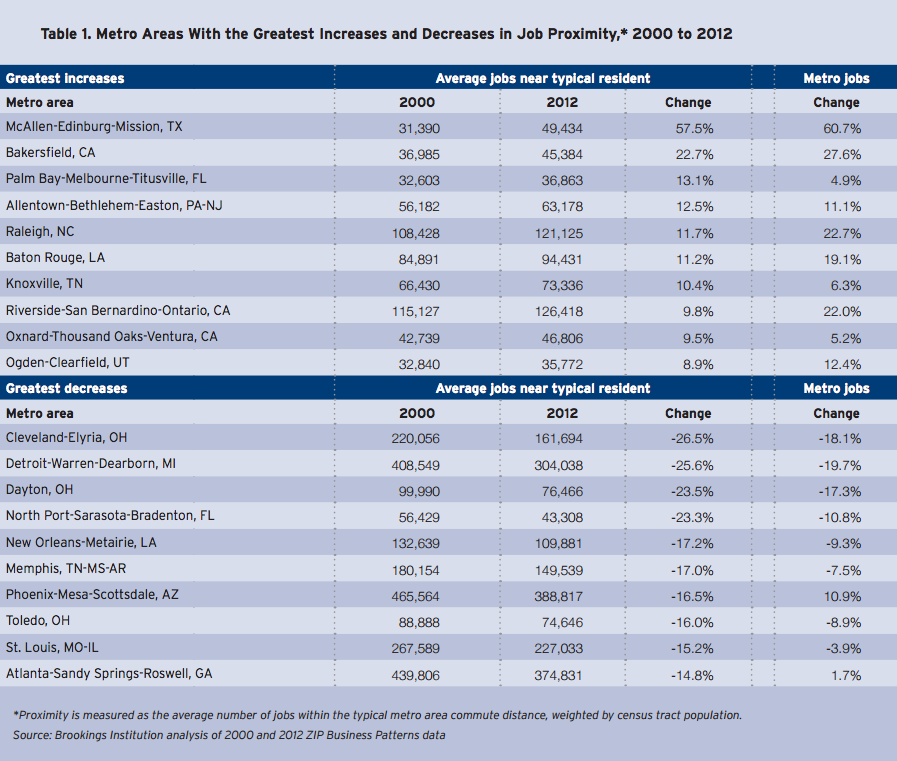

There were exceptions to the decline in job proximity. Of the 96 largest metros, 29 metros, mostly in the South and West, saw the density of job proximity increase from 2000 to 2012 in tandem with net job growth. But the majority of major metros saw job proximity drop, including 37 metro areas that lost job proximity even though total job numbers increased.

(From the Brookings Institution’s “The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America”)

The report says that overall, “61 percent of high-poverty tracts (with poverty rates above 20 percent) and 55 percent of majority-minority neighborhoods experienced declines in job proximity.” Given that 2012 Census data also show that in America’s 96 largest metro areas, 63 percent of Asians, 60 percent of Hispanics, 52 percent of blacks and 55 percent of the poor live in the suburbs, declining job proximity is making life more difficult for disadvantaged communities already dealing with institutionalized discrimination and exclusionary policies.

Anita Hairston, associate director with research institute PolicyLink, explains that the suburbanization of poor and minority residents is rooted in both racism and economics.

“For some poor families and for many people of color it’s really just about discrimination that still exists in the housing market,” says Hairston. “The second piece is around cost. There are lots of reports about folks spending 50 to 60 percent of take-home pay on housing, especially if they’re working in the service sector.”

The Brookings report does not look at where people are actually commuting and how far, but a decline in neighborhood job proximity suggests that people are likely commuting farther to get to jobs. And whereas with inner-city poverty, there’s a chance of better access to public transportation to ease commutes, many suburbs and especially impoverished suburbs, lack good transit options, if they have any at all.

“It’s a real challenge, particularly for people of color where nearly 20 percent of African American and 14 percent of Latino households live without a car. That can really cut off employment opportunities,” says Hairston.

For Brookings’ Kneebone and Holmes, the takeaway from their study is that “the broad trend toward decreases in the number of nearby jobs, and the disproportionately steep declines experienced by low-income and minority residents … should prompt targeted attention and action from regional policymakers and leaders.”

(From the Brookings Institution’s “The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America”)

Hairston says that immediate action should be investment in better metro-area transit, and especially transit built with equity indicators in mind.

“Transportation infrastructure is a real opportunity to really close those gaps in equality. [We need] a transportation system with community indicators focused on economic opportunity such as reducing commute times, reducing cost … particularly for poor people and people of color,” says Hairston.

Some metropolitan areas such as St. Paul-Minneapolis and Seattle have taken steps to include equity in their transportation planning process, but it is not yet the norm.

Kneebone and Holmes point to a similar need, writing, “Building job proximity metrics into such collaborative and integrated [planning] efforts … can help inform more targeted and effective strategies that build better pathways to economic opportunity for communities and residents region-wide.

Hairston says ultimately, the solution lies in fundamentally changing the way we plan our metropolitan regions.

“We just have not had a vision for communities in this country yet that focuses on having people being proximate to place of employment. We’ve depended on individuals being able to get around in a car to get everywhere they need to go.”

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Josh Cohen is Crosscut’s city reporter covering Seattle government, politics and the issues that shape life in the city.

Follow Josh .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)