This piece originally ran on The Transport Politic.

Los Angeles leaders, like those of many major cities, are very interested in improving public transportation access to the airport. Such projects are perceived to be politically palatable transit investments because they appeal to a wide spectrum of the population, including people — especially the economically influential — who do not usually take the bus or train. Unfortunately, even when they’re built, these connections often fail to live up to expectations. Can L.A.’s planned airport rail link do better?

As part of Measure R, the sales tax approved by Los Angeles County voters in November 2008 that will dedicate billions to new rapid transit, $200 million was dedicated to the extension of the Green Line light rail to LAX Airport — a project that has been under consideration for decades. Currently, the Green Line runs from Norwalk to Redondo Beach, mostly along the Century Freeway; customers can switch to airport-bound buses at the Aviation station.

But there is no direct rail service into the airport, and buses entering and circulating around LAX’s eight terminals are slow. As a result, virtually no one takes transit: Today, just 1 percent of air passengers and 9 percent of employees arrive by public transportation. As a comparison, according to the most recent Census statistics, 7.1 percent of Los Angeles County residents take transit to work and 11 percent of Los Angeles City residents do the same.* There is certainly room for improvement.

The problem is that there is no obvious answer about how to connect Los Angeles’ rapidly expanding rail network with the airport. Early plans from 1988 suggested running a line beside or below the airport on the way to Marina del Rey, northwest up the Pacific Coast. By the mid-1990s, a $215 million extension would run as a quick spur from the Green Line, where it would meet an airport people mover.

With little progress on those plans, LAX planners promoted a people mover to run to the existing Aviation station in the mid-2000s, but that effort has not yet been part of the airport’s renovation scheme. Meanwhile, the transit agency won millions of dollars in aid from the federal government for its 8.5-mile Crenshaw light rail line, which will run east of the airport by 2018 and connect to the Green Line, but again, not provide direct airport access.

All this leaves L.A. grasping about for a plan. This year, L.A. Metro planners are performing an alternative analysis on the corridor with the goal of selecting a locally preferred alternative for the route in 2013. All but the most basic route would require more funding than the $200 million currently available, so there is no guarantee that the project will be built this decade; even so, the airport will likely contribute hundreds of millions of dollars in airplane landing fees to the line, so something will probably be built eventually.

Metro developed four basic alignments for the route, as illustrated in the figure at the top of this article. Like the Washington Metro Dulles extension (and indeed most airport links), the agency has two fundamental options: Will it serve the airport directly with rapid transit service, or will it have its customers transfer to a people mover from which they will have access to terminals?

The average customer using the line would save the most time if the light rail line were simple rerouted under the terminal (and this would attract the most new customers), but this would be an expensive and duplicative approach, since it would parallel the north-south Crenshaw Corridor. One obvious question is why the Crenshaw Line wasn’t designed to run through the airport on the way to the Green Line, but it is too far along on the design process to change course now. Other options would provide direct light rail service as a branch from the Green Line or a circulator, either in the form of a people mover or a bus rapid transit line, connected to the Crenshaw Line or an intermediate station.

Of these options, only the intermediate branch idea, with a short light rail line connected to an airport circulator, seems truly out of the question, since it would attract fewer riders, save less time and cost almost as much as the rail rerouting.

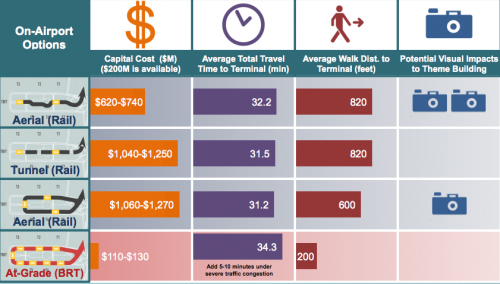

As shown below, Metro has also begun to analyze how the new rail link would approach the terminals themselves. The first three options could be completed by light rail or people mover; the fourth would use bus rapid transit. As the analysis demonstrates, using BRT would be far cheaper, and it would allow people a direct walk to each of the eight terminals (a rail network stopping at each of the terminals would apparently cost about two and a half times as much as a system stopping at just one location, so it seems to have been pulled from consideration). The BRT would be a few minutes slower than the rail system for the average user.

This kind of analysis raises some important questions. With this many terminals, do the two or three stations that are possible with a rail scenario make any sense? Does the flexibility inherent in bus service make things easier for baggage-carrying passengers, or will they be treated to something akin to Boston’s Silver Line, where buses meander between terminals at a remarkably slow pace? Will passengers chose not to use the transit link if it is provided by a bus rather than a rail car? There are no easy answers.

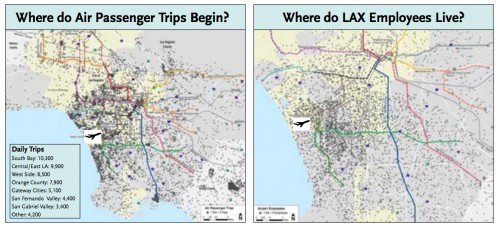

Returning to the original issue, one reasonable question is to ask who might be reasonably be convinced to use this new transit connection if it were built. Consider the following L.A. Metro maps showing concentrations of air passengers and employees:

What seems clear is that while employees live mostly in the neighborhoods around the airport, passengers are concentrated across the westside of Los Angeles, along the Pacific Ocean and Wilshire Boulevard. Will the transit improvements as proposed serve them well?

Certainly, simply branching off the Green Line would save time for people coming from the existing route and the South Bay — in addition to people coming from downtown, who will likely be able to get to airport more quickly using the existing Silver and Green Lines than the future Exposition and Crenshaw Lines (because of the larger number of stops on the latter route).

On the other hand, branching off the Green Line would require those arriving on the Crenshaw Line — in other words, people coming from the Westside, where there is a large airport user base — to switch to the Green Line to get to the airport. This will slow their commutes significantly because of the limited frequencies on the Green Line (just every 15 minutes currently at midday). A more equitable solution might be providing a high-frequency people mover from a shared Green and Crenshaw Line station that ensures that whenever a train arrives, there will be a people mover waiting. This forces everyone to transfer but at least there will be little waiting.

Of course, no matter the outcome, this link will not be the end of the conversation about better transit to LAX. None of the solutions proposed will significantly improve airport travel times for most people in the region, and none of them will get downtown within half an hour of the airport, a goal for most cities. Look to places like London and Paris — despite quite significant (and costly) transit links to their respective airports, they’re spending even more to supplement those lines with more connections. And indeed, L.A. planners have in the past mentioned express trains between Union Station and the airport, via the Harbor Subdivision. Satisfaction is hard to come by.

* Those figures, by the way, put Los Angeles (both city and county) near the top of American cities. This is not a particularly car-obsessed city by U.S. standards.

Images from Los Angeles Metro LAX Extension Project.

Yonah Freemark is a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center at the Urban Institute, where he is the research director of the Land Use Lab at Urban. His research focuses on the intersection of land use, affordable housing, transportation, and governance.

_920_518_600_350_80_s_c1.jpg)