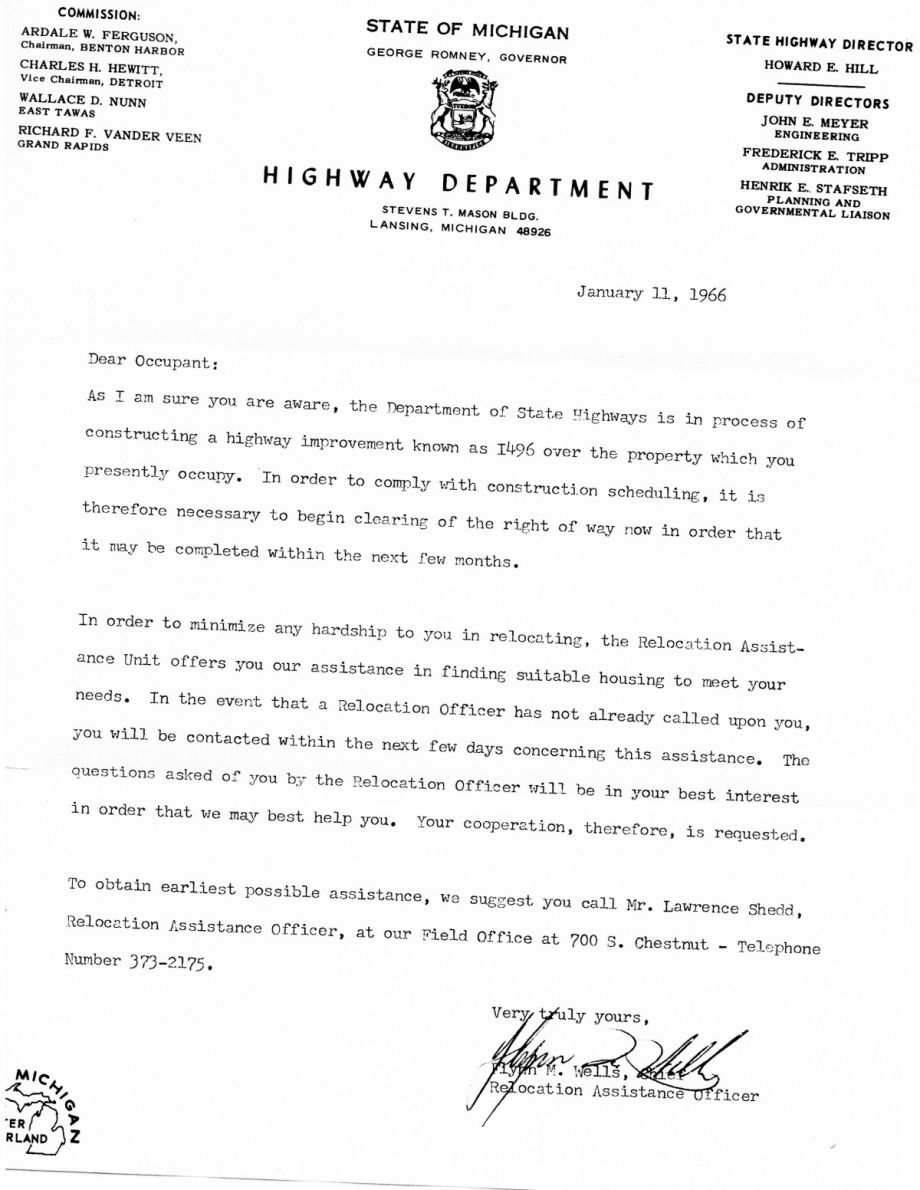

In 1965, Mary Jane McGuire, her husband Cyril and their three children received a letter from the Michigan State Highway Department. It informed them that their Lansing home, where the family had lived for the past decade, would be demolished to make way for construction of Interstate 496. The letter was followed by an offer of federal dollars to purchase their property, a number the McGuires felt was far below its actual value.

The couple’s initial refusal to accept the offer meant they were one of the final families of their African-American neighborhood to be displaced for construction of the interstate. Forced relocation led to an equally daunting challenge: The first offer the McGuires made for a new home was rejected because of their race. They ultimately purchased property in a neighborhood of mainly white residents — a handful of whom left upon news of a black family moving in — less than nine weeks before the state tore down the family house.

“It wasn’t what we expected,” McGuire says. “We had not expected that a highway would come through and our home would be destroyed, that what we designed for ourselves would be destroyed.”

McGuire is now 94 years old. Her story is one of many being told as part of Pave The Way, a citywide project to assess what was lost upon construction of Lansing’s crosstown expressway.

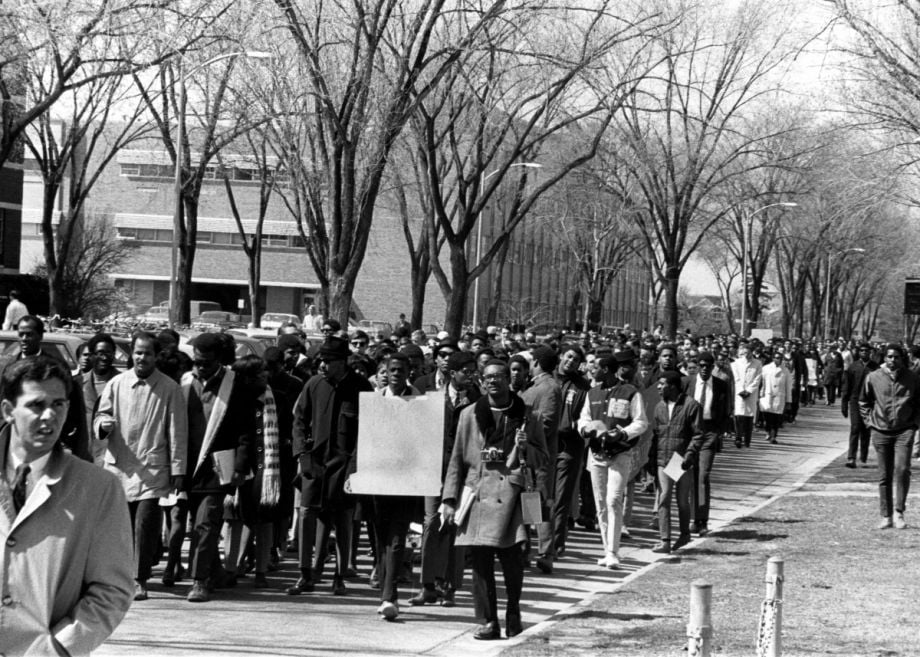

Between 1963 and 1970, over 840 houses and businesses along the St. Joseph-Main Street corridor near downtown Lansing were demolished for I-496. Starting this summer, a range of exhibits prompt the city to acknowledge, honor and discuss this history of displacement fueled by racism.

The Pave the Way project started formally in November of 2018, when Lansing received a $39,400 grant from the National Parks Service to tell the story of the impact of I-496 construction.

The idea was to dig into the full chain of events — which all intersect with race — surrounding the interstate. The tight-knit, African-American community along St. Joseph and Main streets emerged out of segregation. The interstate was constructed to facilitate white flight out of the city. And while relocation was marketed as a “rare opportunity” to break up Lansing’s segregated neighborhoods, in actuality it displaced residents who faced redlining and continued segregation in their efforts to stay in Lansing.

The grant formalized efforts already underway to keep this history alive. A number of displaced residents, like McGuire, remained in Lansing, and some kept photographs, newspaper clippings and documents of the neighborhood and the interstate construction. Two residents who grew up in the area, Kenneth Turner and Adolph Burton, had spent years researching their old neighborhood.

Bill Castanier, president of the Historical Society of Greater Lansing, also started research around the interstate. “I knew [urban renewal projects] went on nationally, I understood it,” he says. But he felt not enough research had been dedicated to the minority community in Lansing affected by it most.

Letter from the Michigan Highway Department. Click to enlarge. (Courtesy Bill Castanier, Historical Society of Greater Lansing)

With the grant the Historical Society could put its weight behind the project, hiring Greta McHaney-Trice, a retired teacher, to direct the advisory committee established by Mayor Andy Schor at the launch of Pave the Way. Committee members, many of whom went through displacement, were selected to help direct the research.

McHaney-Trice is a longtime Lansing resident who studied history and is highly involved in the community. For Pave the Way, she’s helping spread awareness to former residents and family members of the demolished neighborhood, in hopes of gathering artifacts, memories and oral history.

The goal of Pave the Way is ambitious for a limited budget, but it is moving ahead with full steam. The work includes conducting scores of oral histories and interviews (a project led by Turner and Burton); creating a web-based interactive map showing which houses were torn down and where the families moved; establishing a digital portal with the Library of Michigan to host research materials; creating a scrapbook detailing construction and its disruption; mounting a traveling exhibit to visually tell the story; and finally producing a short documentary.

Partnerships with the Capital Area District Library, Library of Michigan, Archives of Michigan and others will help preserve photographs, ephemera and other objects from the preservation effort, which Castanier compares to “an archaeological dig.” So far Pave the Way has collected everything from photographs of cotillions regularly held in the community to cookbooks to relocation notices issued by the highway department.

Burton says there’s something deeply meaningful in uncovering his past history. “My own son doesn’t have a clue where I lived, and we live in the same city,” he says. Now, he’s using photographs to pinpoint old buildings and even build scale models of demolished structures.

This month, Juneteenth marked the first public launch of these efforts. Van tours were held around the St. Joseph-Main Street area “to give a pulse of the neighborhood that’s left, and the one that’s not there anymore,” Burton explains. Pave the Way also presented an exhibit as part of Juneteenth celebrations.

The final exhibit will debut at the Library of Michigan when the grant wraps in early 2020. A traveling exhibit will go to schools, churches and businesses that spring. Oral histories will be made available online and will also contribute to the documentary, Castanier says. Eventually, he’d like to find ways to memorialize the neighborhood along the route of the interstate.

“The whole city changed” with the construction of the interstate and other urban renewal initiatives, Castanier says. By shining a light on what happened specifically along the St. Joseph-Main Street corridor, he believes Lansing residents can interrogate the broader effects of urban renewal.

“The conversation changes when people discover an unknown history,” he says. “It brings people together when they understand that the history of the city is shared.”

Emily Nonko is a social justice and solutions-oriented reporter based in Brooklyn, New York. She covers a range of topics for Next City, including arts and culture, housing, movement building and transit.

Follow Emily .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)