The City of Chicago is facing a $1.2 billion hole for its 2021 budget due to tax revenue declines in the wake of COVID-19. Saqib Bhatti knows exactly where Chicago can find $1.1 billion to nearly fill it in — that’s how much the city coughs up annually in interest payments on its municipal bonds.

Bhatti is the co-executive director at the Action Center on Race and The Economy, where he also co-authored a new report that makes the case for the Federal Reserve to offer zero-interest loans to state and local governments.

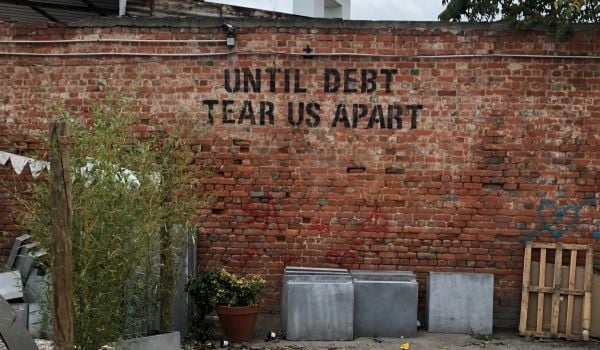

They’re calling it “cancelling Wall Street,” but it could also be called the less splashy “refinancing existing loans.” The report estimates that, by refinancing all of their existing debt into zero-interest loans from the Fed, state and local governments and agencies across the country could save more than $160 billion in interest payments annually. Today, that $160 billion goes to insurance companies, wealthy investors, and some retirees through pension funds and other retirement accounts.

Some cities and states would actually gain money from refinancing all of their existing debt into zero-interest loans from the Fed.

Des Moines is facing a two-year budget hole of $6.4 million. But it pays $23 million in interest payments annually, so refinancing its debt would leave it with a significant surplus.

Denver is facing a $226 million budget deficit. It pays $277 million in interest payments annually.

Bhatti and co-author Brittany Alston analyzed dozens of state and local government budgets to come up with their figures. There are 50,000 state and local governments and agencies that have outstanding debt on the municipal bond market. Getting to $160 billion in savings would require the Fed to refinance all of those governments’ and agencies’ existing debt — $3.8 trillion.

It can be hard to wrap your mind around a figure like $3.8 trillion. Would the Fed ever do that? And how quickly could it come up with $3.8 trillion? But the fact is, it already did that once this year, and all it needs is a few strokes of a keyboard.

“The idea of interest-free loans from the Federal Reserve is something we’ve been talking about for at least the last ten years,” says Bhatti, who started looking into this topic in the aftermath of the last financial crisis, which many state and local governments were still recovering from at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The CARES Act has opened this door,” says Bhatti. “We’re negotiating over the actual terms now, as opposed to whether [the Fed lending to state and local governments] should actually be happening.”

The Federal Reserve today is a very different beast than what economics courses have taught for decades and for the most part continue to teach today. There’s almost an exact date when everything changed — somewhere around September 10, 2008, right at the midpoint of the Great Recession.

Before the Great Recession, the Fed was a relatively passive actor, mostly buying and selling short-term U.S. government bonds to control interest rates, lowering rates to stimulate demand during downturns and raising rates during upturns to stave off inflation. With interest rates already near zero and the Great Recession still in full effect, the Fed started doing something it had never really done before as a way to stimulate the economy — expanding its own balance sheet.

Before mid-September 2008, the Fed’s balance sheet had grown very slowly and steadily for decades to around $900 billion; by mid-November 2008, it was around $2.2 trillion. Most of those dollars were loans to Wall Street banks, but over the next few years the Fed also started adding longer-term U.S. government bonds and also home mortgages for the first time to its balance sheet.

It did it again this year. At the beginning of March 2020, the Fed’s balance sheet was around $4 trillion; by mid-June it was at a record $7.1 trillion. That’s $3 trillion in just three months.

Unlike you or me or any business or any state or local government, the staff at the Federal Reserve conjure up those $3 trillion out of thin air. And it mostly went to Wall Street. Using a few keystrokes and mouse clicks, the Fed bought up tons of U.S. government bonds and mortgage-backed securities from investors on the open market.

As a means to help stabilize the economy, the CARES Act provided guidance for the Fed to use those keystrokes and mouse clicks to grow its balance sheet even more by buying corporate bonds as well as buying municipal bonds issued by state and local governments — both things that the Fed has never done before.

So far, the Fed has bought corporate bonds on the open market from 520 corporations. Its presence in that market has coincided with what Bloomberg called “the greatest borrowing binge ever” for corporations.

Meanwhile, only two municipal bond issuers have borrowed from the Fed — the State of Illinois and New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority. As Next City has reported previously, part of the problem is the interest rate offered to states and local governments — it’s currently set above market rates, meaning most state and local governments can still get a better deal on the open market.

By contrast, the Federal Reserve is currently lending to banks through its “discount window” at an interest rate of 0.25 percent, far below market rates.

“It’s ridiculous,” says Henry Garrido, the head of D.C. 37, New York City’s largest public employee union, with 150,000 members and 50,000 retirees.

Garrido is pushing back against 22,000 proposed layoffs of city employees in New York. He started looking into the Federal Reserve’s Municipal Liquidity Facility as a potential bargaining chip, but the terms didn’t make sense.

Initially, the Fed was offering to make two-year loans to state and local governments. After outcries from state and local officials as well as public employee unions across the country, the Fed extended that to three-year loans. But the interest rate offered is still above market rate.

Garrido’s union is part of a coalition of community organizers and labor organizers that is working with the Action Center on Race and the Economy on the #CancelWallStreet campaign. They’re aiming to get public officials to co-sign a letter to Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, demanding that the Federal Reserve make zero-interest loans available for state and local governments to refinance all of their existing debt.

New York City currently pays around $3.1 billion in annual interest payments on its debt, according to Bhatti’s report. That still wouldn’t be enough to cover what is slated to be a $9 billion budget hole, but it’s a start, and Garrido is also standing with many others still pushing for additional federal aid to households as well as state and local governments.

Preventing or mitigating state and local government layoffs would be right in line with the Federal Reserve’s newfound interest in addressing structural racism in the economy. Such layoffs have in the past and would again disproportionately harm Black workers, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Last week, the presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks in Atlanta, Minneapolis and Boston convened a launch event for the first of a series of discussions looking at various aspects of racism in the economy.

“The reason that we’re having this series is we recognize we have a role to play, not to say it’s somebody else’s problem,” said Neal Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. “We are here to work on behalf of all Americans.”

One of the themes that emerged in that discussion was an admission that the Fed needs to listen more, especially to workers, as opposed to just bankers and business owners. Garrido, whose members include many frontline workers in New York’s city-run healthcare system, says the Fed needs to make zero-interest loans available to state and local governments.

“Frederick Douglass said power concedes nothing without a demand,” says Garrido. “We are demanding that this be part of the conversation.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)