For many, it’s an instinct, a gut feeling they get walking the crane-shadowed streets of cities in hyperdevelopment: New construction brings new money and new residents, and pushes out the old, so curbing housing development in vulnerable areas would stem displacement. But does the data back up the gut?

Last week, as part of the ongoing implementation of the city’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda, Seattle released a report that laid out two scenarios. In one, neighborhoods across the city are evenly upzoned for greater density. In the other, neighborhoods with high displacement risk and low opportunity are upzoned to a lesser degree. The report, a draft environmental impact statement for the city’s new inclusionary zoning policy, gets to the heart of an ideological battle playing out in many cities.

Dan Bertolet of the think tank Sightline Institute sums up the two sides this way: “The typical kind of progressive viewpoint on this has been, when someone comes and builds a new expensive building in the neighborhood it leads to gentrification and higher prices and displacement,” he says. “It kind of makes sense because it’s in your face and you see it. And then the other side of the argument is like from a data side, from a more regional perspective, we know that the main cause of raising housing prices and what we call economic displacement,”— in other words, people moving because they can’t afford rent anymore — “is the shortage of housing. So when you look at it from that angle, we need to build a lot more housing, so upzones are good.”

Those in the former camp, including anti-gentrification and displacement activists, may be disappointed by the findings. The environmental impact statement (EIS) is intended to measure the impacts of the city’s Mandatory Housing Affordability program, which would upzone certain neighborhoods to allow greater development, and then require developers in these areas to include a certain number of income-restricted affordable units in new buildings or pay into a fund for the city to build them elsewhere.

The program has already been implemented in the dense University District, South Lake Union and downtown neighborhoods. The EIS examines the impacts on the rest of the neighborhoods slated for inclusion.

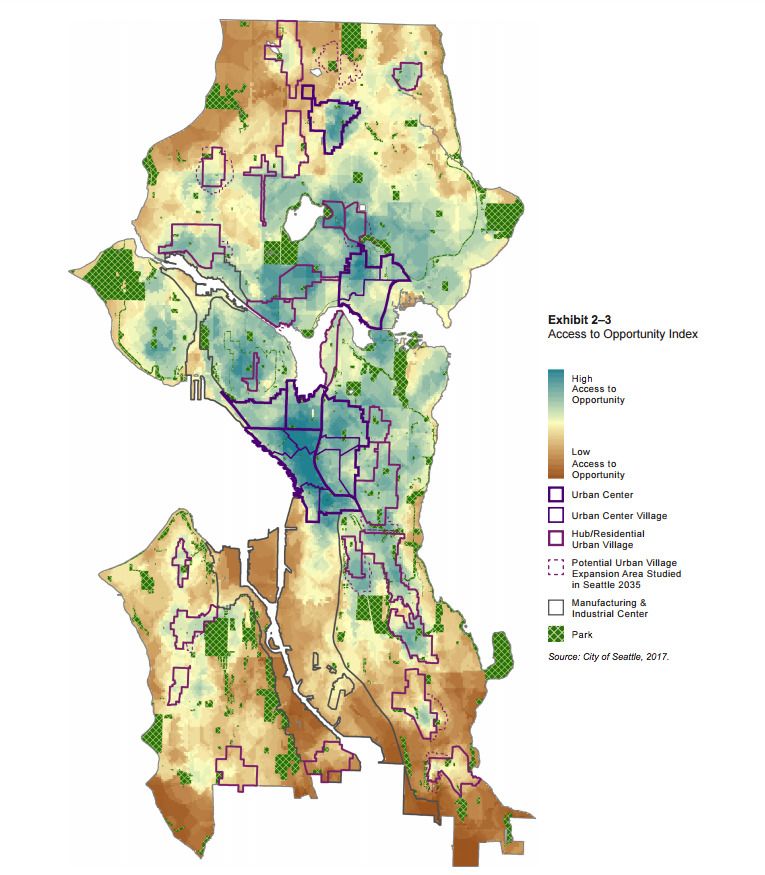

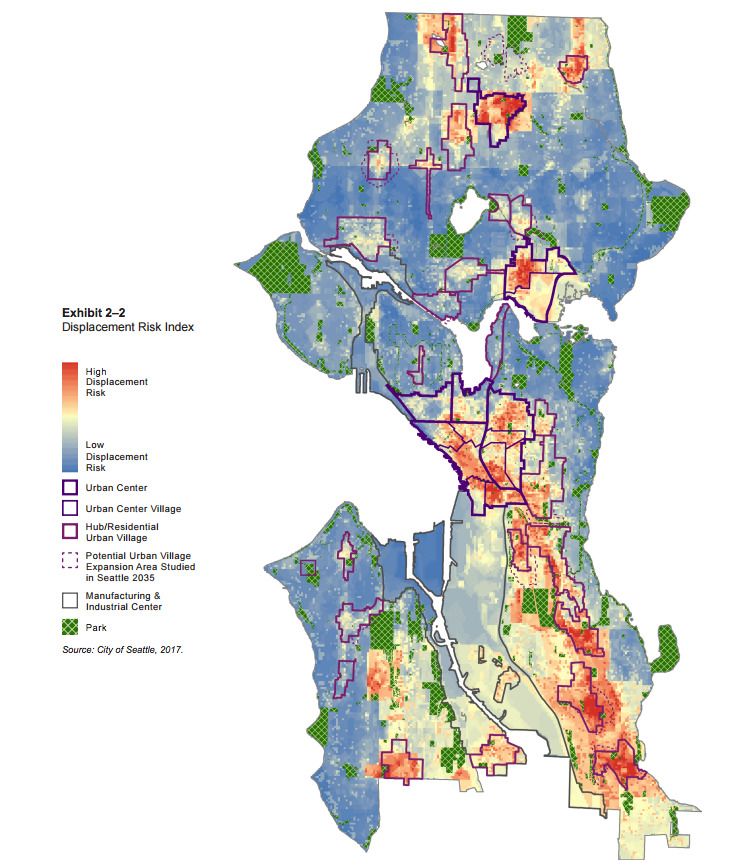

Using an index developed as part of a Growth and Equity Analysis included in the Seattle 2035 comprehensive plan, the EIS categorizes all Seattle neighborhoods according to whether they have a high or low displacement risk, and high or low opportunity. High opportunity corresponds to good access to education, transit, parks and other urban amenities. Displacement risk is calculated based on demographic data — the number of low-income and other marginalized people susceptible to housing pressure — and the demand for housing compared to supply.

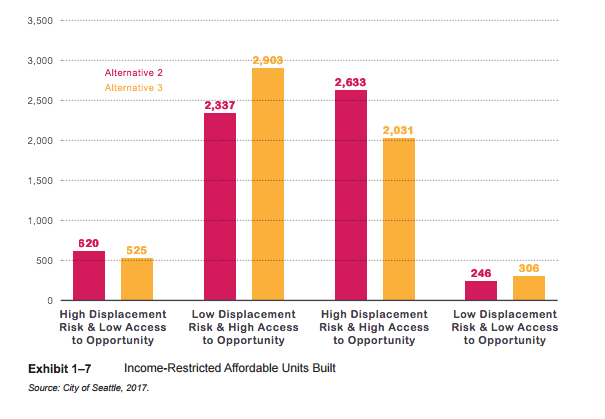

In the first scenario, decisions about how much to upzone individual neighborhoods would be made irrespective of their displacement risk and access to opportunity. In the second, neighborhoods with high risk and low opportunity would be upzoned to a lesser degree. Under both options, the EIS forecasts that the number of households grew by similar amounts: 95,342 citywide under option one, 95,094 under option two. Option one produced 5,717 units of income-restricted housing; option two, 5,582 units.

Breakdown of where new units would be built under the two scenarios (alternative one was to do nothing)

But did restricting density in high-risk areas stem displacement, as measured by a change in the number of low-income households?

“We actually found that the displacement of low-income households correlated more strongly with high-opportunity areas than it did with high risk displacement areas,” says Geoffrey Wentlandt, senior planning manager at the Office of Planning and Community Development. “And what we actually found is that historically there’s a moderate correlation between the areas that have grown more in terms of adding housing units, and an increase in the percentage of low-income households. So counter to what a lot of people might think and compared to what we’ve seen in the past, areas of Seattle that have grown the most have retained the most low-income households.”

The finding reflects one made last year by California’s Legislative Analyst’s Office: Bay Area communities with the greatest increase in market-rate housing were also seeing the least displacement.

In some ways, this should be intuitive, says Bertolet, as intuitive as the feeling of encroachment when new high-rises replace mom-and-pops. He points to the Central District, Seattle’s poster child of displacement: The historically black neighborhood has until recently seen little new housing development, and yet has seen the percentage of its black population dwindle from 70 percent in the 1960s to less than 20 percent today. It’s so close to downtown, says Bertolet, that regardless of upzoning, it was bound to experience housing pressure. Without new development, demand and prices for what few houses there were skyrocketed fast.

Wentlandt says upzoning should not be the primary tool to try and stem displacement, though. “There’s lots of other tools to mitigate displacement and further equity that are outside the scope of this MHA EIS proposal,” he says, pointing to the city’s Equitable Development Initiative.

Bertolet agrees. Among other strategies, the city should be ensuring local businesses can stay in place, and shoring up community institutions, he says. But despite the data, he’s also cautious of drawing the conclusion that upzoning won’t hurt communities of color, like those in the Central and International Districts, and low-income residents.

He points out that the Bay Area study was later challenged by two researchers who showed that yes, on a regional level building market-rate housing may reduce pressure and stem displacement, but that on a neighborhood level, new luxury buildings signal to wealthy buyers and developers that a neighborhood is ripe for investment, potentially changing the character of a place such that former residents feel unwelcome.

“To me it’s almost more important, the conceptual debate,” Bertolet says. Community groups are insisting that upzoning will harm them, in neighborhoods where residents’ wishes have been ignored for decades. “So the question is, should the city make its policy according to what these community groups are saying? Or should they weigh the best available data that they have, which says, that’s not going to help?” he asks.

He recommends walking a bit of a middle ground: Do upzone high-risk areas, but still concentrate more growth in the wealthier, whiter, less at-risk areas. And then allocate some of the money developers will pay if they don’t build affordable units to support anti-displacement efforts in vulnerable neighborhoods.

Public comment is being accepted on the draft EIS until July 23. Final versions of the Mandatory Housing Affordability plan and its EIS will be released this fall, followed by more public comment and a city council vote summer of next year.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Philadelphia Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. She is currently a student of radio production at the Salt Institute of Documentary Studies. See her work at jakinney.com.

Follow Jen .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)