Thomaston High School, located in Thomaston, Connecticut, has a total of 428 students. Throughout the entire high school, there are only 16 Hispanic students and 6 black students.

Just 18 minutes away via car is Crosby High School. It is one of the 29 schools in the Waterbury School District. According to data provided by nonprofit Edbuild, which advocates for fair public school funding, Waterbury receives $4,471 per pupil less in annual funding than students in the Thomaston School District.

Crosby is a Title I school, and thus receives the highest possible amount of federal funding. Title I school districts are given supplemental funds due to their high concentration of low-income students. Even with increased federal funding, however, Crosby High School remains severely underfunded.

Will Clark, chief operating officer of Waterbury Public Schools, says that even though the school “cobbles together what we can,” meeting the needs of his school district is “a growing challenge.” The district has its own full-time grant writer and often sees funding success. But Waterbury, like many urban districts, has responsibilities beyond the school day. Students from low socioeconomic backgrounds, English language learners and students with special needs benefit from school-sponsored support. Waterbury offers health clinics, after school services, mentoring, and free breakfast and lunch programs, all of which cost money.

A new report from EdBuild outlines the reason public schools can have such great funding disparities. The report, Dismissed: America’s Most Divisive School District Borders, shows that a high concentration of poverty and minorities in towns and cities has created heavily segregated school districts.

Edbuild maintains that this issue is not national, but local.

A large portion of public school funding is driven by local property taxes. Taxes drawn from lower income neighborhoods are unable to provide the same revenue that wealthier and whiter districts receive from middle to upper class neighborhoods. On average, Edbuild reports, wealthier and whiter districts receive funding that adds up to over $4,000 more per student per year.

The report also explains that these disparities are due to “divisive borders,” “invisible lines… quarantining students of color.” State-drawn district borders tend to segregate based on class, and consequently, race.

“We never solved segregation,” says Zahava Stadler, Edbuild’s policy director. The case that allows for segregation, she says, is Milliken v. Bradley. That 1974 Supreme Court case, a response to an order to bus students across school district lines to better schools, proclaimed that states had the right to draw school districts however they saw fit, even if those district borders resulted in segregation.

After the court ruled that school districts did not have an obligation to desegregate across district borders unless they had been built with racist intent, educational segregation — a direct result of redlining and unfair housing policies — continued.

Milliken v. Bradley, which was brought to the court two decades after Brown v. Board called for integration, ended a potential future for inclusive school districts. Before Milliken, Stadler explains, “we were moving [in] a direction with a conviction that governments can’t create unequal schools for different kids.”

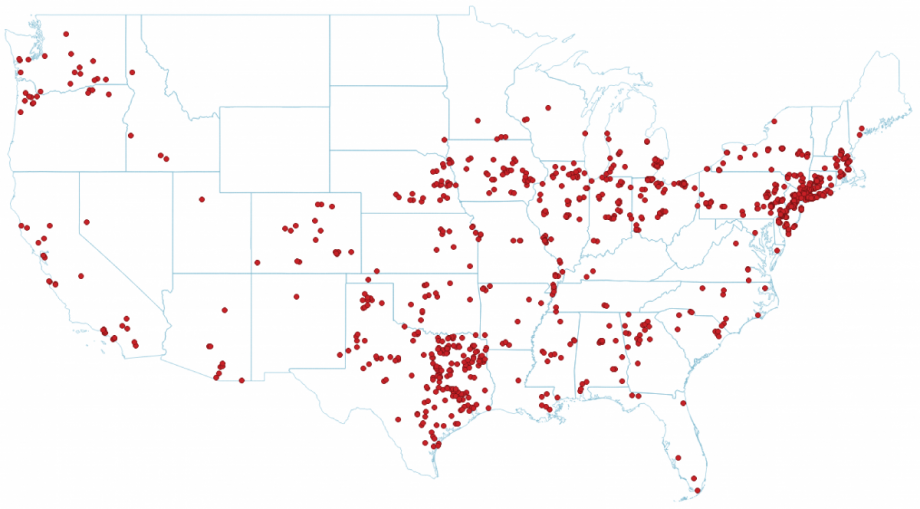

The report finds that there are almost 1,000 borders separating school systems that are racially isolated and severely underfunded in comparison to their neighbors.

Edbuild was able to find 11.2 million students attending schools on either side of those borders. Edbuild chose to define a border as divisive if a district had at least a revenue gap of 10 percent in comparison to its more advantaged neighbor and a 25 percent difference in racial makeup, with whiter districts receiving higher revenues.

“All 11.2 [million students in divisive districts] are worse off because they are in less diverse classrooms, but 8.9 [million] kids are one the losing side of the line because of revenue gaps,” Stadler explains. Of these disadvantaged school districts, black and brown districts tend to be even worse off than low-income white districts.

Connecticut is one of the richest states in America, recognized widely for its impressive public schools, but this wealth does not spread across all districts.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the median household income in the Waterbury area is $39,681. Nearly half of the residential families in the area receive food stamps, and over ⅓ of family income falls below the poverty line. The district, which serves over 20,000 students, is 56 percent Hispanic or Latino, and 21 percent black. A majority of parents of children in the public school system have not gone on to higher education while over 20 percent remain unemployed.

Thomaston school district is 96 percent white. Parents of Thomaston students have a median household income of $82,159, more than double the median income of parents in the Waterbury district. The district, which has only three schools, is able to allot a much higher amount per student.

According to Edbuild, Waterbury is the most isolated school district in the United States, surrounded on all sides by divisive borders that prevent students from attending wealthier, better resourced schools.

Waterbury and Thomaston aren’t the only segregated schools in Connecticut. The state has somewhat of a history when it comes to school funding policies and accusations of district segregation.

In 2016, Connecticut was ordered by Judge Moukawsher to reevaluate and redesign the entire public school system because it failed to provide a fair education to lower income students. The state later appealed and in January of 2018, the Supreme Court overruled Judge Moukawsher’s decision, citing that Connecticut had already fulfilled its minimal constitutional duty, putting an end to education reform funding.

Equal opportunity isn’t an easy problem to tackle. If local governments raise taxes on already struggling communities, their communities will only struggle more. The federal government already funds schools in impoverished neighborhoods, and it isn’t enough. Stadler offers a better solution: States can redraw borders into larger, more inclusive districts.

States where district borders are drawn wider, like Vermont, West Virginia and Nevada, seem to have less divisive borders and fewer isolated districts, lessening the gap between their students.

Larger and more diverse districts offer all students from different socioeconomic backgrounds equally resourced school districts. Students are more likely to excel in smaller classrooms, with better teachers and more resources. Additional resources, specifically for low income students, can have long term effects on overall success and employment.

If Waterbury receives more funding, Clark already has plans on where those dollars should go. “Technology and security are areas we can use more funding… we made significant investments [in technology] but the lifespan is short. We need to make continued investments.”

Natalia Rommen is the 2019 Next City urban affairs journalism fellow. She is pursuing a degree in Political Science and Communications at the University of Pennsylvania. Previously, she sat on the board of Penn’s African American culture club where she managed the club’s marketing and event planning. In 2019, Rommen was selected as a data analytics fellow for Penn Program on Opinion Research and Election Studies. Rommen uses her experience with statistics to research urban development and policies that affect minorities.

.(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)