About two years ago, the city of Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development was considering revising its affordable housing ordinance, which had not required affordable units to be built on the same site as tax-subsidized developments. Developers pushed back, citing, for one, a high cost for building on-site affordable units.

“When we were trying to counter some of those arguments, it became really clear to me that there was this conception that our status quo was cost neutral,” says Marisa Novara, a researcher at the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC), a Chicago research organization.

Novara and her colleagues at MPC believe Chicago’s status quo of housing segregated by race and income was holding back the whole city and region, not just low-income communities and people of color. But they didn’t have the data to back up their assertion. Or at least, they didn’t have Chicago-specific data. So they decided to gather the necessary evidence to make their case.

“From the literature and other studies that have been done at the national level, we know that areas with higher levels of income inequality and higher levels of separation by income and race do more poorly economically,” Novara says.

In partnership with the Urban Institute, they’re now looking at the 100 largest metropolitan regions in the country and doing some comparatives of where Chicago ranks among a host of variables. Per capita income, educational attainment, violent crime and more. They’re in the process now of trying to see where Chicago comes out in comparison to other metros along those variables and what they think might change if they were able to lower levels of segregation.

“If we lowered segregation by a certain amount, would people’s incomes rise by a certain amount? Those are some of the variables we’re working through right now,” says Novara.

Using other cities as benchmarks is a challenge, of course. “We’re certainly aware that comparisons to other metros are fraught with standalone phenomena,” says Novara. “I think we can control for a lot in the comparisons we’re doing.”

Ultimately, Novara and her team want to isolate policy changes that create more or less racial and economic segregation. “There’s been a fair amount of research that economies suffer, that even middle- and upper-income families pay a price if economic segregation slows down regional growth,” Novara says.

For instance, Novara explains, typical economies require people of different skill levels to be able to come together in a workplace and combine productivity. When people cannot afford to live close enough together and have very long commutes for low-paying jobs, then those positions are hard to fill. “That’s a way that we can see how even when parts of the economy seem to be doing well, what we know from other research is that it appears they could be doing even better if people of a greater range of skill levels were more able to efficiently reach the same places of work,” Novara says.

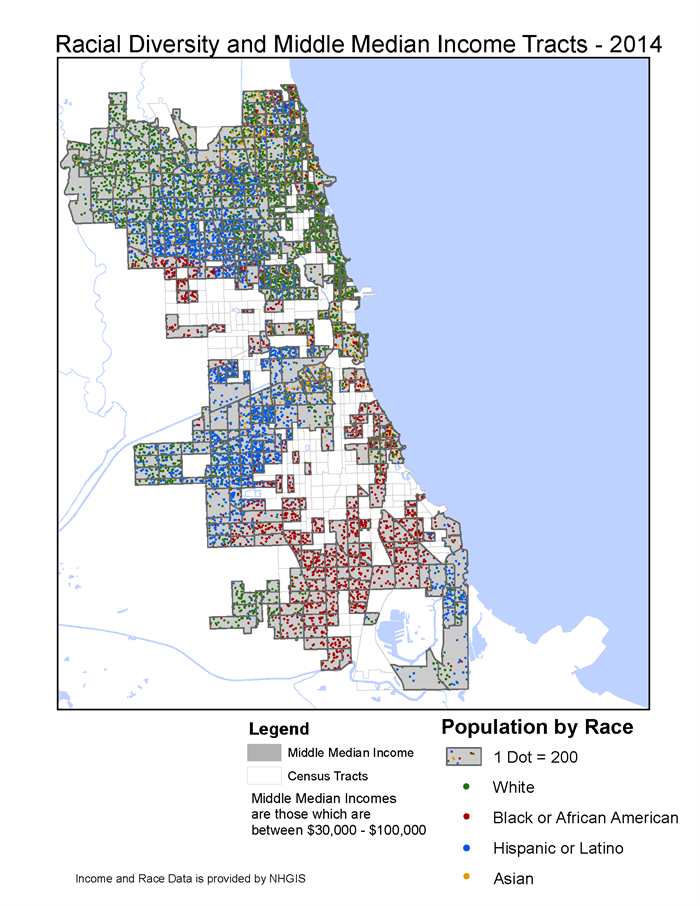

They’re still a few steps before being able to make their final case. For now, what they’ve found is that middle-class Chicago neighborhoods that are made up mostly of black and Latino residents tend to be surrounded by black and Latino neighborhoods that are lower-income, while the city’s mostly white and middle-class neighborhoods tend to be surrounded by neighborhoods that are wealthier and mostly white. It effectively means there are two economic ladders in Chicago, one for people with white skin and one for everyone else.

“You could have a white, middle-class person on the North Side with similar income to a black, middle-class person on the South Side and while their income may be comparable, their experience living in this city and the wealth that they are able to create is incredibly different,” Novara explains.

MPC is also a member of the Preservation Compact, which brings together public, private and nonprofit leaders primarily to preserve affordable multifamily rental housing in Cook County, which contains Chicago. The group gathers data and tries to suggest policies that would work for all factors in the affordable housing equation. Lately, the Preservation Compact has been exploring an idea that grapples directly with the issue of neighborhoods segregated by race and income: incentivizing multifamily property owners to provide public housing units inside privately owned buildings located in high-income neighborhoods.

Their idea is based on HUD’s existing project-based voucher program. Under this program, local housing authorities guarantee rents for a limited number of units in privately owned buildings, and places low-income, Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher-eligible families into those units. Usually, local housing authorities are limited to paying landlords fair-market rent, meant to be a roughly average rent across each municipality. But, thanks to a 1960s lawsuit against the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA), Chicago is allowed to pay market-rate rents to landlords in high-income markets, specifically in areas designated by CHA as “opportunity areas.”

The problem is, not as many building owners in high-income, high-rent markets are biting as CHA would like, even with CHA guaranteeing them market-rate rents. Why? “Because working with CHA is like poking your eyes out,” says Stacie Young, director of the Preservation Compact. “There’s a burden in terms of documentation. You’ve got to let inspectors into your units. You might have to make changes and have them come back. This is a bureaucracy, this is the government.”

The Preservation Compact has been talking with CHA, developers, investors, brokers, public housing residents and other rental market participants to design an incentive for owners in high-rent markets to join Chicago’s project-based voucher program. For now, they’re calling it the Strong Markets Initiative.

In a hypothetical example, Young explains, say a developer wanted to acquire and renovate an existing small or mid-sized apartment building in a high-income neighborhood for $10 million. Typically, they would need an $8 million bank loan and a $2 million down payment. The Preservation Compact is exploring the creation of a fund that would provide super low-interest loans to developers to cover part of the down payment, in exchange for participating in Chicago’s project-based voucher program.

“That’s our idea, not a requirement to build affordable housing, but an effective incentive to provide affordable housing through the project-based voucher program,” Young says. “We’re still making sure it’s something owners would actually do, making sure that it’s going to be able to function as a vehicle.”

While they’re still working out a lot of the details, the Preservation Compact has submitted a $5 million request to the CDFI Fund Capital Magnet Program to seed the Strong Markets Initiative fund. There are also other, low-cost sources of capital that the group already has access to, such as the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system, although it is early days yet, according to Young; the group has not yet considered the FHLB system as an option.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)