EDITOR’S NOTE: This sponsored content is paid for by the Center for Cultural Innovation (CCI), as part of its AmbitioUS initiative. This series explores how alternative economic models can empower artists and culture bearers, with an eye toward financial freedom and long-term sustainability.

That’s what makes collective action so important. It’s also why the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers launched a “Justice At Spotify” campaign earlier this fall.

“With the entire live music ecosystem in jeopardy due to the coronavirus pandemic, music workers are more reliant on streaming income than ever,” their statement reads. “We are calling on Spotify to deliver increased royalty payments, transparency in their practices, and to stop fighting artists.”

Linares, who’s part of the campaign outreach team, says the industry’s ability to exploit those artists is especially true for Black and Brown creators, whose cultures are often “extracted and packaged and whitened” to make it more marketable, she added. “Representation alone is not power.”

She should know. Linares has over a decade of experience working to represent artists and musicians in the industry. But having worked in the belly of the beast, she says, she started to wonder: could there be a better way to help artists actually benefit from their labor? She’s now the communications lead for the New Economy Coalition, a Massachusetts nonprofit that works to help organizations move collectively to build alternative economic structures — structures specifically modeled on the concept of solidarity economy.

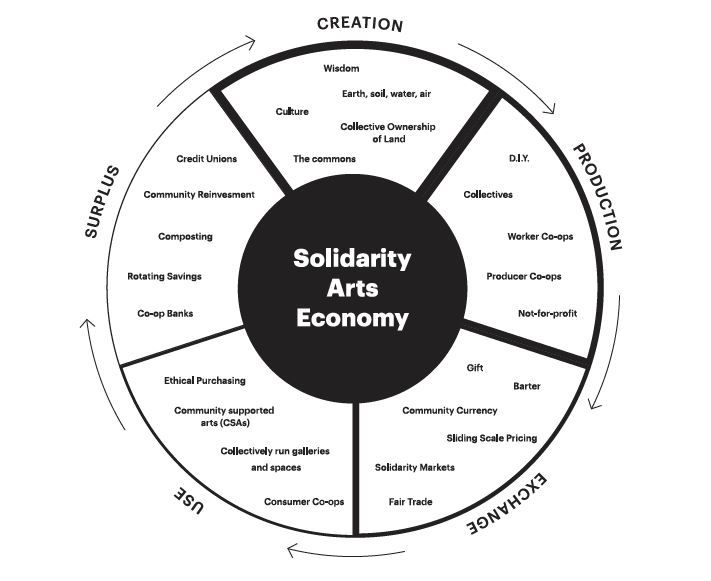

The solidarity economy is rooted in a post-capitalist framework that first emerged in Latin America and Europe in the 1990s. It can include fair-trade organizations, worker co-ops, gift economies, and more. The model’s defining characteristic is that it centers cooperation and community, often with an increased focus on social and environmental justice.

In the days leading up to the election, union leaders discussed the possibility of a general strike should Trump refuse to concede the election. While that strike has not (yet) materialized, it points to the increasing power of unions, collective organization and alternative economies building across industries; that includes artists of all stripes.

What has prompted this movement towards collectivism?

Part of it, of course, is the coronavirus pandemic. As work grows increasingly less stable and government aid remains unreliable, those in the arts have recognized the importance of community over competition: museum workers pushing to unionize in Philadelphia; performers mobilizing to strengthen contracts in LA and New York; and entertainers in Santa Fe considering unionization after layoffs or pay cuts. While art has often been framed as an individualistic practice, collectivization could be critical to its survival.

But at the same time, Linares says, artists’ relationship to and reliance on collectives isn’t new.

“The ‘New’ Economy Coalition is totally a misnomer [because] a lot of these solutions are our ancestors’ solutions,” she adds. Collectives have existed as long as artists have; in the United States, worker cooperatives’ history is directly informed by Reconstruction. Capitalism may dominate now, but alternative economies never really went away.

“If you look locally wherever you are, I’m pretty sure there is a group of people trying to build Black liberation infrastructure, where that’s community gardens, credit unions, public banking, a grocery co-op,” Linares says. “When you actually organize and look around you, there is a lot of hope there.”

(Illustration by Jeff Warren and Caroline Woolard)

And it’s not limited to local, or even national, frameworks.

“The solidarity art economy connects community-run initiatives like artist-run spaces and mutual aid networks for artists to larger initiatives for economic justice, like credit unions and land trusts,” says Caroline Woolard, solidarity economy artist and founder of Trade School, a self-organized learning community that ran on the barter system. She points out that similar economies in other countries have provided a base of political power and shared resources, both now and in the past.

In the short term, Woolard and Linares’ work involves campaigns such as Justice at Spotify, grassroots fundraising and direct action, the use of barter networks, and mutual aid among artists. Long term, it might involve building structures such as community land trusts and housing co-ops, which allow for solidarity economies’ continued growth and expansion.

These structures aren’t unique to artists, of course. But both Linares and Woolard insist that artists play a critical role in the growth of a solidarity economy because art itself is necessary to bring about social change.

“Artists have a sense that there are many different kinds of labor and knowledge,” Woolard says. “[They] add spaces of reflection to moments of political uprising… they can add sensation: dancing, singing, visualizing.”

Artists’ work shapes the bounds of our collective memory and imagination, “not only about what has happened, but of what we’re capable of doing,” Linares says. “It’s a cultural [as well as economic] shift… everything that we’ve been taught needs to be unlearned.”

Caroline adds: “It’s really about — how do we dream toward a world that we want, together?”

The New Economy Coalition’s slogan, according to Linares, is “fire the bosses, free the land, elect ourselves, build a new economy.” It’s a compact motto, and an increasingly appealing one for artists and makers across the country.

“What’s exciting about any moment of shared crisis is that more people realize the necessity for cooperation, mutual aid, and solidarity art economies than did before,” says Woolard. “It’s a moment for Nati [Linares] and me to say, okay, we’ve been doing this work… we’ve been [doing this] for a long time.”

Marginalized communities — groups of queer people, disabled people, and people of color — have been speaking out against capitalist-created crisis and towards solidarity economy for a long time. Thanks to 2020 and the pandemic, Woolard says, “more people are listening.”

Hannah Chinn is a freelance writer for Next City. She's also a reporter for WHYY News, covering watershed and environmental issues in Philadelphia, PA. Previously, she reported neighborhood news and city planning and policy stories for WHYY’s PlanPhilly.