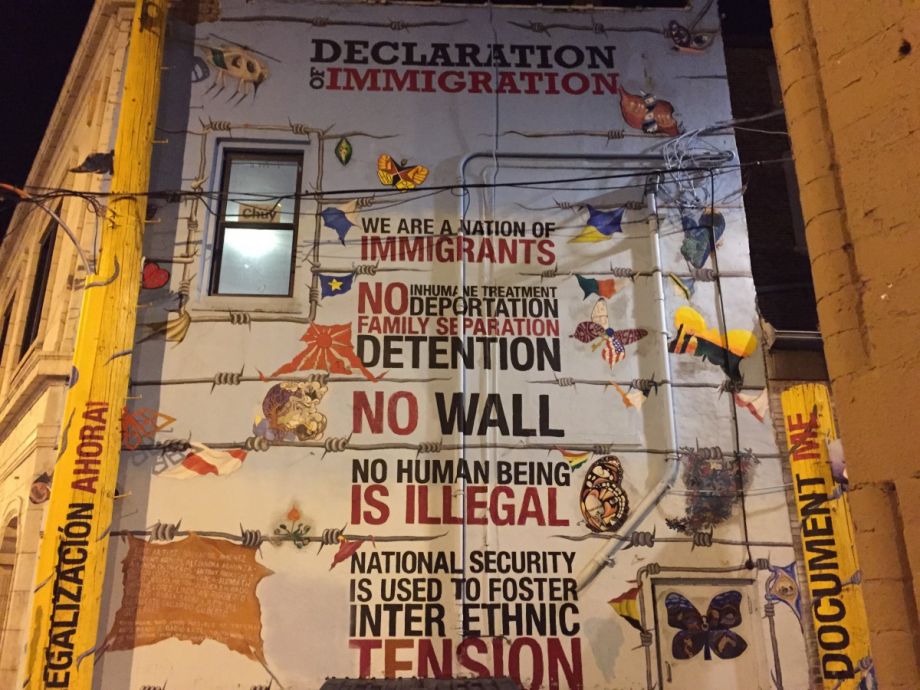

Along an alleyway in Pilsen, on Chicago’s West Side, there’s a mural of the “Declaration of Immigration.” In all caps, it reads: “We are a nation of immigrants. No inhumane treatment, deportation, family separation, detention. No wall. No human being is illegal. National security is used to foster inter-ethnic tension.” The telephone poles on either side are also painted, and one says, “¡Legalization Ahora!” and the other says, “Document me.”

Yesenia Cervantes was born in Pilsen, and split her childhood between there and Mexico City. She attended USC, but she’s been back in Pilsen for about 15 years now. “It has been changing the last 15 years,” Cervantes says. “It used to be 100 percent Mexican. Now it’s a little more diverse.”

According to the latest American Community Survey, Pilsen is 52.1 percent Mexican. The population is mostly first and second generation, says Cervantes, who works at nonprofit Instituto Del Progreso Latino. She leads its Center for Working Families, which provides over 500 clients a year with a range of job placement and supportive services.

“The people we serve are mostly young adults, between 35 and 45 years old, and as far as income, usually around $35,000 a year on average, and three to four people per household,” she says.

Recently, Cervantes has been involved in an effort to connect community-based organizations and financial institutions through the Meeting Halfway program.

“We have always worked with financial institutions, but I feel like we never had a solidified coordination among nonprofit organizations in the neighborhood connecting with the banks,” she says. “I thought this was a great opportunity to convene and form a community to address challenges in the financial arena and build out those relationships.”

Meeting Halfway has its roots in the Los Angeles Riots of 1992 — or, rather, the underlying conditions that made the city ripe for the racial discord those riots represented. Twenty-one foundations came together after the riots to examine what they could do to address that tension effectively. They started by asking people what they really wanted. What they learned was that people wanted banks, number one, and supermarkets. “It wasn’t exactly a total shock, but I think it was a wake-up call,” says Elwood Hopkins, who worked for the group. “It was an exceptional moment in L.A., one of those moments after a crisis when people are genuinely open-minded, like gosh, I have to re-learn everything.”

The experience led Hopkins to launch Emerging Markets, a consultancy that works directly with banks to figure out how to effectively serve low-income neighborhoods.

“We’ve since worked for about 10 of the major banks, hired by them to open up branches in different neighborhoods and develop all of the business models and staffing structures and product mixes and all of that,” says Hopkins. “We then found that there was a real need to do some parallel work in the communities where these branches were being opened. So we created a parallel entity called the Emerging Markets Development Corporation (EMDC), a nonprofit, that works in neighborhoods to help till the soil and prepare them to partner with a financial institution.”

Meeting Halfway represents the next evolution of that work — a codification of all that EMDC has learned about how to cultivate healthy partnerships between banks and historically marginalized communities.

Chicago is one of four cities where EMDC recently took the Meeting Halfway curriculum. (It’s also working in NYC, L.A. and Miami.) LISC Chicago convened organizations focusing on three neighborhoods, Logan Square, Englewood and Pilsen. Groups that work on financial stability identified priorities and things they could do to have an impact.

In Pilsen, Cervantes’ Instituto worked with Mujeres Latinas un Accion, Spanish Coalition for Housing and Alivio Medical Center. The priorities they identified were financial education for youth, financial product awareness and small business lending.

“When people come to find employment, many of them are interested really in starting up their own businesses,” says Cervantes. The Meeting Halfway partners in Pilsen have hosted several recent discussions with small businesses from the neighborhood. “We learned that a lot of entrepreneurs don’t have an established credit score,” she adds.

The Pilsen group also put out calls to local financial institutions. The first to respond were First Midwest Bank and Second Federal, a division of Self-Help Federal Credit Union. Representatives of each have participated in small business discussions organized by the group. At one October event, out of 25 entrepreneurs in the room, Cervantes says about 20 needed a loan.

“[In the curriculum] we look at credit unions, big banks, regional banks, online financial services. We don’t look at them with a particular point of view, it’s sort of just looking at the advantages and disadvantages of partnering with each,” says Hopkins.

Cervantes says the most helpful part of the curriculum was explaining all the different ways to negotiate partnerships with banks — from loans to courses that banks can offer themselves like small business financial coaching to referral relationships.

The next step for EMDC might be putting its lessons into action itself.

“Most banks don’t open up new branches in low-income neighborhoods. They usually inherit or buy them,” says Hopkins. “But what if we were to create a financial service provider in a low-income neighborhood and then sell it to a mainstream bank.”

EMDC calls it the “branch lab” concept. A single “branch lab” could even be resident-owned, so that when a mainstream buyer comes along, the residents profit.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)