Nick Torsitano, 25, is about a year and a half into his physical therapy doctoral program at Temple University, and he’s got roughly another year and a half to go until graduation. Even though he’s still paying off debt from his time as an undergrad at NYU, Torsitano says financing his education at Temple is entirely on him, so he’s taken out a lot of student loans to pay for it.

“I haven’t ever thought about owning a house because of the debt I have. I’ll either be older in my life or I’m just never going to do it,” he says. “I know that I’ll pay them off eventually — even if it takes me 20 years to do it, that’s kind of okay with me, because I found something that I really like.”

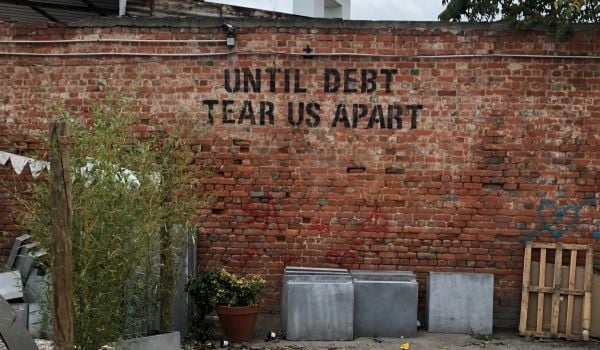

There are plenty of people in Philadelphia, like Torsitano, who recognize that student debt will greatly impact their spending behaviors and financial freedom far into the future. For some dealing with student debt, that might mean delaying bigger purchases, like buying a home or throwing a wedding; for others, it might mean moving out of the city in search of lower cost of living or for more job opportunities.

The burden of student debt on the city isn’t a new issue. Pennsylvania has been ranked as having some of the highest levels of student debt in the country. According to an interactive map released by Generation Progress, the youth advocacy and research group of the Center for American Progress, many zip codes in Philadelphia County have “astronomical” or “extremely high” loan balances.

Lately, though, there seems to be an appetite among City Council members to do something about student debt’s impact. Last year, Councilwoman Cherelle Parker introduced a resolution to investigate the burden of student debt on older borrowers. And last month, Councilman David Oh proposed a bill that would grant a $7,500 tax credit over five years for those who owe at least $35,000 in loans.

That bill faced criticism and stalled in Council. If Oh revisits it, which he says he plans on doing, it raises the question: How might a tax credit alleviate the impacts of student debt on the city, if at all?

Oh says the core goals of the bill are to keep Philadelphia competitive with other metro areas and retain residents, as well as to promote personal investment in education.

“The city has failed to fund community college. Had that money been spent, we would have better resources, better pay, better facilities,” he says. According to Oh, there is a need to support prospective students facing rising tuition costs — community college students, but also for those at more expensive universities — in order to incentivize investment in education and keep the city’s workforce prepared for jobs of the future.

“So, what I looked at was competitiveness … The city of Philadelphia recognizes that you are investing in yourself at a great expense to yourself. This is a small help,” says Oh.

But those who criticize the bill question whether a tax credit of this kind could have any real impact on changing the behavior of high earners graduating with college debt and might simply act as a giveaway to people already planning to stay.

“I’ve only seen research for state-level tax credits, but they tend not to influence behavior,” says Doug Webber, an economics professor at Temple University. “If you’re talking about high earners — someone, let’s say, making $150,000 a year — well, if you’re making $150,000 a year you’re not going to make a decision that is so important based on $1,500 dollars.”

“$7,500 wouldn’t keep me in Philadelphia if I got a job opportunity somewhere else,” says Torsitano. “It would definitely be a nice help for me, obviously every little bit helps. But my priority would be on getting a job where I can, because some people come out of undergraduate or graduate school and don’t get employed. But I could definitely see for the average student who has $20,000 in debt, you know, $7,500 dollars is getting pretty close to half.”

Webber also argues the bill wouldn’t help those most at risk for defaulting on their student loans, who typically have between $5,000 to $10,000 in debt. “The fact that it’s limited to people with more than $35,000 in debt — that means that the people who are struggling the most, by definition, are shut out,” says Webber. “All the people who went to the local community college — it’s really hard to accrue that much debt. If you’re unemployed, you don’t get anything.”

In response to criticisms of the bill, Councilman Oh says he’s open to eliminating the $35,000 threshold for the credit, but the increase in cost would be even tougher to pass than the original proposal, which would cost taxpayers roughly $50 million. He says that the city could do a lot more in other ways to support education and the student debt crisis, but it’d cost far more in resources than is currently available. The tax credit could act as a compromise.

One alternative posed by Webber would be a tax credit that mimics earned income tax structures: “You could think about it two ways: either a person is only eligible for the tax credit if their income is below some level — less than $100,000 or something. That would be the simplest way to do it. Or, a better way that’s a little more complicated would be to structure it like the earned income tax. That way you can be sure the people who are claiming it are not super high-earners.”

Oh says he plans to take the tax credit legislation to the public for a more extensive discussion. “I’m simply trying to provide a benefit to any person who is carrying debt or is thinking about the fact that they might not want to invest in education. While we as a municipality cannot address the overall situation, I think we can, and everyone should, do something.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Rachel Chernaskey is a freelance journalist and editor currently based in North Carolina. Prior to freelancing, she served as the managing editor at Philadelphia magazine. Her writing has appeared in The Guardian, The New York Times and The Charlotte Observer, among others.