You can take the immigrant out of the city, but you can’t take the city out of the immigrant. For proof of that, look to leafy Montville, Connecticut, where a popular casino is drawing tourists and an influx of Chinese-American immigrants from New York City and Boston. The community is one of several across the U.S. that’s grappling with the increasing urbanization of suburbs. The odds that its economic and population growth will lead to a place of equity remain largely unknown.

Montville is the subject of “SubUrbanisms: Casino Urbanization, Chinatowns and the Contested American Landscape,” a new exhibit at the Museum of Chinese in America, in New York City’s Chinatown.

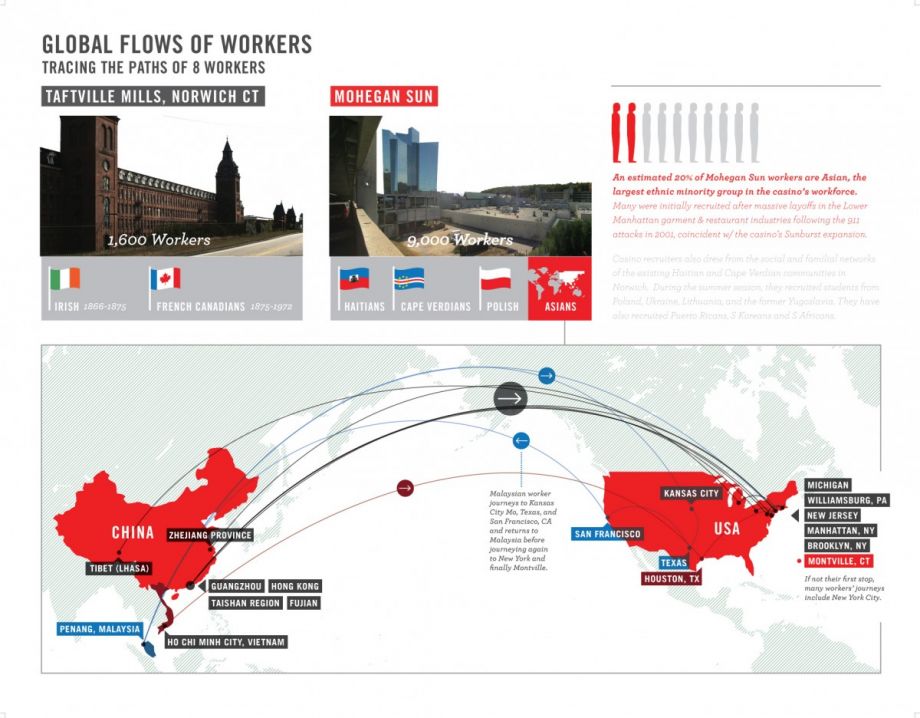

It all started with the major expansion of the Mohegan Sun Casino, in 2001. Owned and operated by the Mohegan Tribe, the casino is almost perfectly halfway between Boston and New York, attracting clientele from both sides and beyond. It has been attracting lots of Chinese-American clientele, in particular. An estimated 25 percent of Mohegan Sun clients are of Asian descent. There’s an Asian-themed section inside. You can get on a bus from Chinatown in NYC or Boston, come to the casino, and go back without ever speaking English.

Partly because of the desire to serve those clients, and partly because of 9/11 leading to an estimated 8,000 garment and restaurant industry layoffs in and around New York’s Chinatown, the casino has been recruiting and attracting a lot of Chinese-American labor.

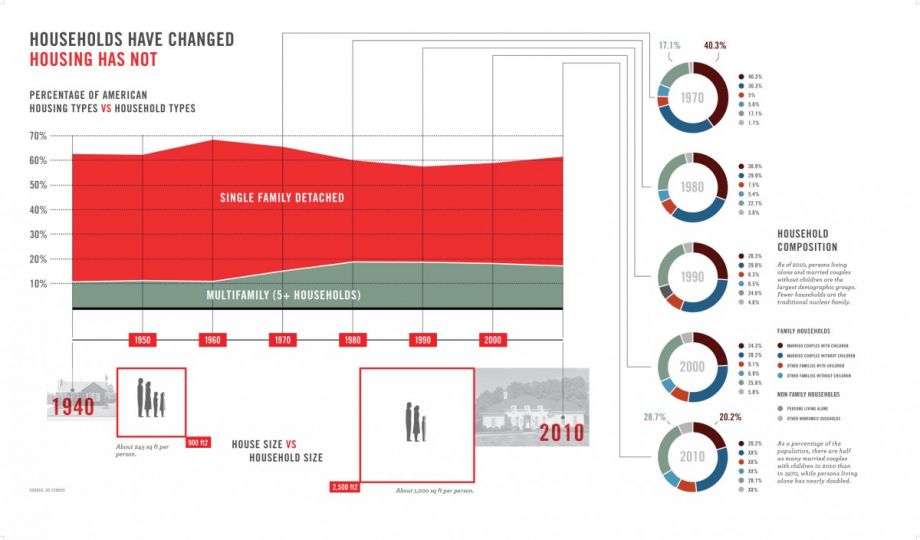

Accustomed to the far more dense and walkable communities in more traditional Chinatowns in the U.S. (as well as in China), these recent and long-term immigrant workers are challenging what life can look like in what might otherwise be considered a suburb.

“This type of development blurs the distinction between city and suburb,” says Stephen Fan, guest curator of the exhibit and adjunct professor of architecture at Connecticut College. “It shows how immigrant groups are bringing urban notions of density, diversity and dynamism into a seemingly suburban fabric.”

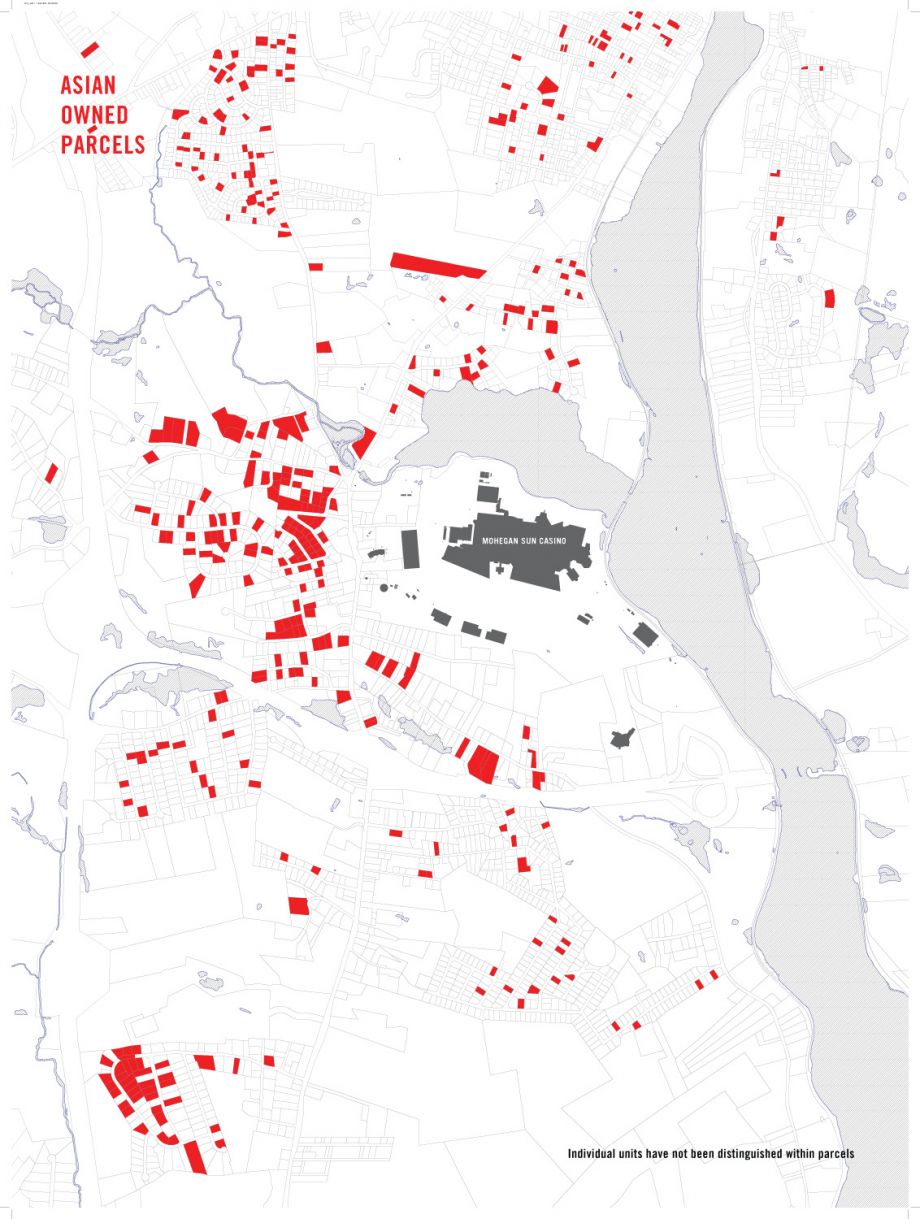

An estimated 20 percent of the casino workers are now of Asian descent. They’ve “crowded” into the existing suburban housing stock near the casino — mostly detached single-family homes with large open floor plans. The design and structure allows for a lot of flexibility, Fan says, letting them subdivide otherwise common areas into multiple improvised private spaces using bed sheets or more robust materials, in order to increase capacity beyond the number of existing bedrooms. Many of the adapted homes are owner-occupied; others have been purchased by investors from Chinatowns in NYC and Boston.

“These new inhabitants are informally filling in the typical role of designers, architects, even planners,” Fan says. “There’s a logic, structure and organization behind what may seem like informal adaptations.”

The new exhibit is largely about challenging perceptions.

One common misperception: Most of the casinos workers are low-skilled. Yet Fan has met, among others, a former bank manager and a teacher who are now busboys at Mohegan Sun. Some employees are there to help pay for their kids’ college tuition or support other family members. Some are semi-retired and sought out a quiet, verdant, walkable community.

Because a lot of the Chinese-American workers walk to work, long-time residents also typically presume they can’t afford cars.

“For many of the casino workers it’s a choice,” Fan says. They see the clean air as a cherished resource relative to the urban air quality in China. They walk even though there are often no sidewalks on the streets around the casino. Some have had to blaze new trails through public areas as well as privately owned spaces.

All of the above has led to friction with the long-time residents of the area.

The exhibit features images from inside some homes, as well as evidence that despite the friction between the mostly English-speaking long-time residents and the mostly Chinese-speaking new residents, the influx of new labor and business has been good for many in the area, at least financially. Montville residential property values rose concurrently with the influx of workers. Neighboring Norwich, Connecticut, hosted a delegation of Chinese investors (which led to a minor scandal due to lack of experience with international diplomacy protocol).

Another misperception the exhibit seeks to challenge is that this living situation is nothing but a last resort. While many workers headed to the Connecticut casino during the post-9/11 Chinatown recession, that is presented as one of many options they had, given the extensive network of Chinese-American communities and business around the country. It’s a network that has previously overcome exclusionary actions by states and local governments — specifically the occupancy standards and unrelated persons regulations in cities like San Francisco and New York.

“These standards largely emerged in the late 19th century when there were valid public health concerns tied to tenement housing,” Fan says. “But in part those arguments masked actual agendas to exclude or discriminate against immigrant populations.”

Fan, by no means claiming policy expertise, suggests creating policy to respond to the negative effects of density, rather than density itself.

“If we focus on those negative aspects, staying open to other types of living situations, we’d move closer to a much more inclusive society,” he says. “It would also open up new possibilities, new housing types beyond micro-units or SROs, new ways of designing communities.” The last part of the exhibit features some of Fan’s visions to that end.

Fan is the perfect person to tell this story. His family is of Chinese decent; they’ve been living in the area near the casino since the late 1980s. It’s where he grew up. A lot of the tensions seen today aren’t new.

“When my father planted vegetables in our front yard, my mother was against it for fear of offending neighbors’ aesthetic sensibilities,” he says.

His family owns the Golden Palace Restaurant in Montville, which has been adapted by, and made to adapt to, the recent influx of Chinese workers. A Chinese accountant sets up shop at a table in their restaurant during tax season; her business card lists the restaurant and somewhere down in NYC Chinatown. They had to shift from stereotypically Chinese-American fare to more authentic Chinese cuisine, like Dim Sum, requiring his parents to hire a new chef from China.

Fan draws many comparisons between the experiences of the new Montville Chinatown, and the “sharing economy” and other emerging ways of organizing economic life. While the Ubers and Airbnbs of the world have billions in venture capital and get lots of great headlines, “This community is getting cans thrown at them from people driving by,” he says.

The casino meanwhile has become a regional center of life, a city on its own. The WNBA’s Connecticut Sun play their home games at the facility. There’s a farmers’ market on top of the parking garage, and plans to build an indoor space for it.

Around 40,000 people are on the grounds on a typical weekend. Most are clients, some driving from hundreds of miles away. Others are workers, some walking from hundreds of yards away.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)