There’s a clickety-clack sound coming up behind New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and his mission to ban horse-drawn carriages in Central Park. It’s the sound of Chicago Alderman Ed Burke.

With penchant for following in the footsteps of Big Apple initiatives such as banning super-sized soda drinks, Styrofoam cups and e-cigarettes, Burke is calling for an end to the equine coaches in the Windy City. Both Burke and de Blasio base their protests on the thought that it’s inhumane for horses to tug carriages in the heat of summer and the deep freeze of winter, often while inhaling car and bus fumes.

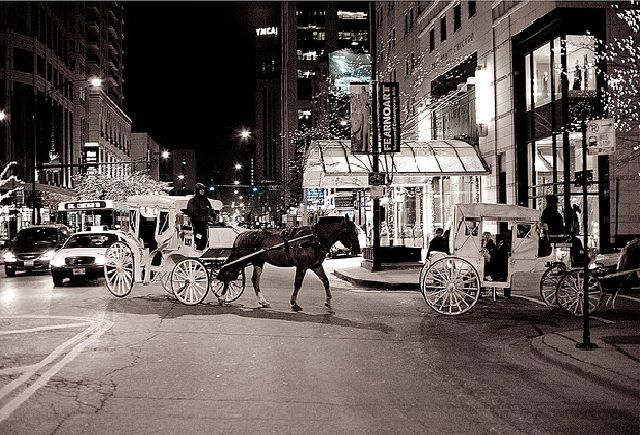

“Why do I want Chicago to do this before New York?” asks Burke, who oversees the city’s 14th Ward, during a phone interview. “Once again, it will show that Chicago takes the lead in good causes and we’re going to get this to shift soon.” Burke points out that in New York, the horses can at least enjoy the peace and beauty of Central Park. In Chicago, their route takes them down the city’s congested shopping district along North Michigan Avenue, also known as the Magnificent Mile.

Animal rights groups such as PETA are on board. Mayor Rahm Emanuel has also backed Burke’s proposal, glibly stating that it would catapult his plan to modernize and overhaul the city’s transportation system by 2020.

Chicago currently issues 24 carriage licenses at a cost of $500 each, down from 65 about five years ago. Carriage operators — three exist in the Windy City — say that business is on the decline due to the high cost of feeding and stable rental for the horses. Many add that younger people aren’t as interested in horses as in years past. Combine all this with the economy, and ridership has decreased.

As Burke set the stage for a public hearing and debate continued in New York, carriage operators nationally were surprised when word spread that horses no longer tour Central Park. Shock set in when the idea spread to Chicago. Peggy Best, secretary of Carriage Operators of North America (CONA), a national association representing carriage companies, says there’s fear that Chicago will serve as a “springboard” and that neither the politicians nor the animal activists understand that these horses are bred for the work.

“I don’t think the politicians understand that those of us who have carriage companies love horses,” says Best, who runs Yellow Rose Carriages in Indianapolis. “Operators across the country are shocked by the possible bans. They have people thinking that because a carriage horse walks with its head down that the horse is depressed. We choose a heads-down horse for this kind of work, and many come from the Amish who work with heads-high horses in the field.”

Best adds that she’s certain that the fate of carriage rides in city will be a hot topic at CONA’s convention next month in Atlanta.

But there’s more poop to this story than meets the eye.

Environmental advocates are also chiming in, asking why Burke isn’t more focused on banning cars, adding that raw animal power is actually making a comeback with a younger generation taken to urban homesteading, manual plowing and do-it-yourself movements.

In 2010, communities on the outskirts of Paris dumped the garbage truck and began using horse-drawn wagons for waste and recycling pickup. The French climbed on board, advocating that it cut back on the cost of fuel, emissions and noise, favoring the soothing clomp of horse hooves over roaring diesel engines. And in the Sicilian town of Castelbuono, Mayor Mario Cicero employed two back saddle donkeys for glass and cardboard collection in 2007. Cicero won over a skeptical public and has since increased the donkey-driven pickup.

Among those puzzled by a possible Chicago ban is Ken Dunn, an organic farmer and founder of the Resource Center, specializing in recycling and reuse. It’s already a Windy City law that horses pulling carriages must be diapered. In 2011, another ordinance required coach drivers to stop and deodorize the street each time their horse urinated. The contents of the diapers are saved for Dunn, who gathers two tons of the manure monthly and converts it into compost for urban gardens and private businesses.

Dan Sampson runs the Noble Horse Carriages, founded in 1979 as an extension of his grandfather’s livery service that’s been around 1891. Sampson says he started giving carriage rides in the city at the request of former mayor Jane Byrne, who wanted carriages at Navy Pier for the yearly ChicagoFest. Since then his Amish bred-and-raised draft horses have plied the Magnificent Mile year round.

When the city required that carriage horses wear diapers, it was Sampson, along with his Amish team, who happily created the design.

“There are operators who aren’t the best, but that’s not true of most of them,” Sampson says. He argues that all eyes are on Chicago and that even the Amish are concerned whether regulations will reach their farms, given that many now take their horse-drawn buggies into towns and small cities.

“I’ve told Alderman Burke that he’s chasing the wrong issue,” says Sampson, who adds that neither Burke nor the city has talked to carriage operators. “Why not focus on animal abuse in slaughterhouses and factory farms?” Other carriage advocates ask why the city isn’t coming down on operators of horse racing tracks that often have deep political ties.

Should the proposal pass and a ban ensue, Sampson says that several other venues for horse-drawn carriages exist in the state. Moreover, like Dunn, he believes that in time more towns and cities will follow in France’s hoofsteps, employing horses as fewer autos and more bikes take to the world’s streets.

Dunn has long considered a horse-driven recycling and compost delivery program for Chicago, but says that endearing city leaders to it is a long way off. Ideally, he’d like to see recycling stables located every 1.5 miles in the city and have a horse-drawn deliver service incorporated into the city’s transportation system. “An environmentally sound city and a sustainable city,” Dunn says, “is run on horsepower.”

Lori Rotenberk is an award-winning journalist based in Chicago. Her work appears on Grist and Civil Eats. She’s written for the Boston Globe and the New York Times and was a staff reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times.