Seattle’s median strips, front yards, and telephone poles are plastered with colorful signs this week, which can mean only one thing: election season. Primary day is Tuesday, August 6 for a city council election with seven seats up for grabs and only three defending incumbents.

That amount of turnover has brought candidates out of the woodwork, a record 55, two-thirds of whom are participating in a first-in-the-nation experiment in public election financing called democracy vouchers.

Every registered voter — plus adult non-registered citizens and green-card holders who request them — receives four $25 paper vouchers (now also redeemable online) early in election season that they can distribute to the participating candidates of their choosing. Candidates who receive vouchers are restricted to spending no more than $75,000 in the primary and another $75,000 in the general, and may receive individual donations of no more than $250 per donor. If their opponent or an “independent entity” (more on those later) spends more than $75,000, the candidate can be released from that cap.

Seattle voters approved a ballot initiative in 2015 to launch the vouchers, which are funded by an annual $3 million property tax levy. Last month, the program won a Washington Supreme Court case challenging its legality on free-speech grounds, so the vouchers are likely here to stay — pending voter reauthorization in 2025 — and will expand to the mayoral election in 2021.

According to the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission, which oversees the program, democracy vouchers have spurred interest from Albuquerque, Austin, New York, San Diego and San Francisco. D.C. is working out the kinks in its new publicly funded elections program this year. In May, 2020 presidential hopeful Kirsten Gillibrand proposed going national with so-called “democracy dollars.”

Democracy voucher proponents hoped that offering potential candidates an alternate route to launching a viable campaign — one beyond having a well-established donor base or self-financing from personal wealth — would encourage a more diverse slate of candidates.

“We were trying to create a viable path to be competitive without using big money,” says Margaret Morales, a researcher at the Sightline Institute, a Seattle think tank that helped conceive of the program.

For several candidates among the top voucher recipients that were surveyed by Next City, the answer is clearly yes.

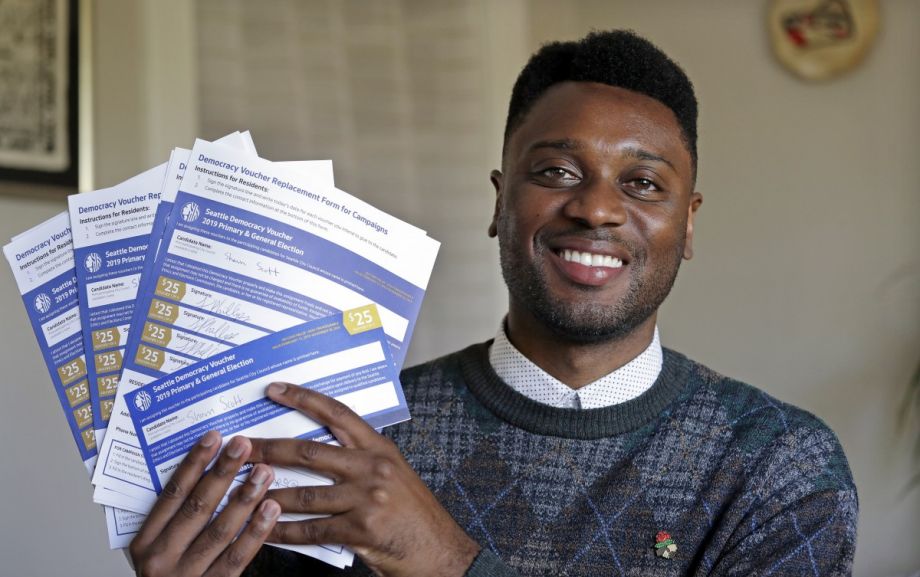

“Democracy Vouchers are a way for candidates who would never be able to run, especially working-class candidates and candidates of color like myself, to not only be competitive but to win and deliver real material change to Seattleites who need it most,” says candidate Shaun Scott, who has raised over $100,000 in vouchers as the citywide top voucher recipient and is running as a member of the Democratic Socialists of America.

“My campaign has been able to deliver forward-thinking policy solutions such as progressive taxation that may not be popular among wealthier political donors.” (Scott’s campaign pioneered new approaches to voucher cultivation, like a “suggested donation” of vouchers at campaign events, which were appealed to the election commission and found to be valid.)

Scott put the matter more bluntly on Twitter: “I’m a Black working-class Millennial candidate with a net worth of approximately $10,000. If it weren’t for the democracy voucher program, running for office would be a pipe dream.”

Democracy vouchers have also helped erode traditional incumbent advantage. Sitting councilmember Lisa Herbold has redeemed $63,075 in vouchers, as of the most recent figures available, making her the number one spender with voucher dollars thus far. (Candidates can receive vouchers pledged to them without spending them immediately.) Her opponent, former police officer Brendan Kolding, has been able to match her nearly dollar for dollar with $61,075, despite entering the race “without any significant name recognition and no experience securing cash donations from people,” he told Next City.

The voucher program has another goal, besides getting more diverse candidates into the field: Get candidates talking to more voters. “We wanted to get more people involved in the political conversation because all of a sudden everyone is a $100 donor,” Morales says.

This is the second election in which the vouchers have been used and records show 3 percent of vouchers have been donated before the primary, a tripling of the 1 percent from 2017 and on pace to potentially match the nearly 6 percent of eligible voters who donate to campaigns in Vermont, the highest rate in the nation.

“The success of the program has blown everybody’s expectations out of the water and we are hitting every single benchmark, including getting a greater diversity of Seattle residents to donate,” says Morales.

There is also anecdotal evidence of success on that front. Ami Nguyen, a former public defender and the daughter of Vietnamese refugees, has been canvassing senior housing in Little Saigon to encourage elderly residents, many of whom have never donated to a campaign or even met a candidate, to pledge their democracy vouchers to her campaign, which has redeemed more vouchers than any other candidate in her district.

“The democracy voucher program has allowed me to reach out to politically marginalized communities,” she tells Next City. “The democracy voucher program has allowed me to connect with communities who don’t have any money to spare but are in the most need of a political voice, including seniors relying on social security benefits or families who are living paycheck-to-paycheck.”

But there is an elephant in the room. U.S. court decisions have ruled that political action committees (PACs) can inject unlimited amounts of cash into elections even at the city council level, providing they do not coordinate directly with candidates.

In a heated campaign following hot-button issues like last year’s big business tax and ongoing civic angst around homelessness, big money has poured into the race. The Seattle of Chamber of Commerce has amassed a $1 million war chest with six-figure donations from Amazon — which vigorously opposed the business tax — and other local business entities, while largely remaining mum on its political intentions. UNITE HERE Local 8, the Pacific Northwest’s hospitality union, has already spent nearly $150,000 on candidate Andrew Lewis, double the caps set for democracy voucher recipients. SEIU 775, a home care and nursing home workers union, also has nearly half a million dollars. Former city councilmember and interim mayor Tim Burgess started his own PAC, which has raised nearly $300,000. A new PAC called Moms For Seattle appeared out of the blue in late June, raising nearly $200,000.

Voters themselves will decide whether PAC money or democracy vouchers will sway the election, with ethics and elections commission executive director Wayne Barnett arguing PAC money is not a guaranteed winner. “If you are supported by deep pockets, a certain number of Seattleites are motivated to vote against you,” Barnett says. “I don’t know whether democracy vouchers will be an effective counterweight to independent spending because I don’t know if [that spending] benefits or hurts.”

Voucher-fueled candidates, meanwhile, are hoping their financing choice bodes well on the integrity test.

“My hope is that the democracy voucher program will have voters question where and why candidates are receiving money from sources other than vouchers, especially from corporate PAC money,” Nguyen says.

Nguyen’s competitor, small business owner Pat Murakami, is more sanguine. “Democracy Vouchers alone are not an effective counterbalance to the mega PACs spending more to promote a specific candidate than that candidate has been able to raise on their own,” she says.

Both candidates are facing socialist incumbent Kshama Sawant, who opted out of democracy vouchers and has raised money from a base of small donors in Seattle and across the country. She is a major target of the chamber-backed PAC, which is her campaign’s argument for why they would be at a disadvantage taking democracy vouchers.

“I believe less PAC money would have been spent if all candidates had participated in the Democracy Voucher Program and had honored the $75,000 primary limit,” Murakami says. Her argument is a kind of voluntary deescalation — if everyone had agreed to the limits of democracy vouchers, there would not have been an arms race between corporate-backed PACs and Sawant’s small donor network, both of which are perfectly legal but also contribute to making local elections outlandishly expensive.

“From the beginning, it was clear there would be a flood of corporate PAC money in this election,” says Sawant’s campaign manager Chris Gray. “It would have been foolish to assume that we would be released from the program early enough to be able to counter a flood of negative mailers and ads financed by corporate cash.”

According to the elections commission, Sawant’s opponents were released from the $75,000 spending cap by mid-May. It wasn’t because a PAC waded into the race — Sawant’s own campaign spent that much. None of the six-figure PACs in the Seattle race responded to requests for comment by press time.

But for Morales, the flourishing of candidate and voter conversations taking place across Seattle this past month are proof of a successful experiment in renewing democracy.

“No amount of PACs will change that,” she says.

Gregory Scruggs is a Seattle-based independent journalist who writes about solutions for cities. He has covered major international forums on urbanization, climate change, and sustainable development where he has interviewed dozens of mayors and high-ranking officials in order to tell powerful stories about humanity’s urban future. He has reported at street level from more than two dozen countries on solutions to hot-button issues facing cities, from housing to transportation to civic engagement to social equity. In 2017, he won a United Nations Correspondents Association award for his coverage of global urbanization and the UN’s Habitat III summit on the future of cities. He is a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners.