Deep in the Amazon basin, Checherta, Peru, has a population density of just one person per kilometer. The village has 21 houses of two rooms each. Each is an open hut of wood and reeds, supported by poles, not walls. As many as six families live in each.

Yet Checherta’s modest means actually offer its inhabitants one benefit that medical scientists say city-dwellers lack: protective bacteria. This week, a New York University research team released a study that compared the microbiome of people in this tiny village to populations in three larger cities and towns in Peru and Brazil. (Checherta is near the border between the two countries.) The result was clear: Urbanization creates massive change in the microorganisms we carry with us — and this can trigger a downward change in health status.

“We think that the epidemic increase in asthma, allergies, Type 1 diabetes, Celiac disease, [and] obesity are related to disturbances in the microbiome,” Maria Dominguez-Bello, lead researcher and a microbiologist at NYU’s Langone Medical Center, told NPR about an earlier related study.

The microbiome is the total complex of living microorganisms living in and on the human body. In recent years, medical science has begun increasing its attention to it, in part as a means to control infections that commonly arise when the body’s “good” bacteria is too low relative to “bad” (disease-causing) bacteria. Some efforts have focused on avoiding practices that kill protective and helpful bacteria, such as overuse of antibiotics. Other efforts have focused around increasing “good” bacteria through exposure to microorganisms, which will help the body keep harmful species in check or develop its immune system.

This represents a major shift for health and urban planning. For centuries, urban design for public health has largely focused on decreasing contact with microorganisms as a way to limit acute, deadly infectious diseases. Changes in handling sewage in order to avert cholera epidemics was the impetus for London’s first public health feats, for instance. In 19th-century New York City, improvements in crowded tenements helped address tuberculosis outbreaks.

But the connection between microorganisms and chronic diseases is becoming clear. At present, many scientists are investigating theories that a cumulative effect of microorganisms in the body over time influences how the body develops chronic diseases. (A study released this week by a team at Seoul National University in Korea assessed 40 identical twins and found a high risk of developing type 2 diabetes correlated with changes in digestive system microbiota.) Rather than optimizing sterility, the best protection against harmful microorganisms is now thought to be about an optimal balance of beneficial ones.

Dominguez-Bello’s study investigates that through a novel approach. Rather than comparing samples of saliva, skin or bodily wastes from human subjects, researchers swabbed floors, walls and furniture of their homes — in other words, the surfaces that humans routinely contacted, picking up microorganisms and leaving others behind. A lab analysis determined the diversity of species in the samples, and researchers compared the findings across four areas in the Amazon basin.

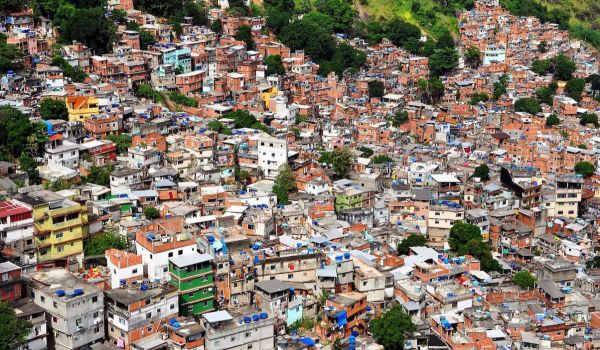

The first, Checherta, was the tiny homestead in the Peruvian section of the Amazon jungle. The three others were successively larger: Puerto Almendras, a rural town on the Peruvian side of the border; the 371,000-person town of Iquitos, also in Peru; and Manaus, an urban center of 2 million people that serves as the capital of Amazonas, Brazil. In each place, researchers sampled 10 houses.

The findings were simple and important to note in a world of rapidly growing cities: the more urban the setting, the less diversity in the microbiome of the samples.

“Our study found that urban living spaces increase the number of human-associated microbes we are exposed to,” Dominguez-Bello said in a press release, “while decreasing our exposure to the outdoor, environmental microbes with which humans co-evolved.” In the jungle, those non-human-associated microbes included bacteria and viruses found in soil, spiders and other animals.

The study attributed the reduced diversity in urban homes with walls separating distinct areas of function (such as the kitchen from the bedroom) from one another. Dominguez-Bello’s team also found wearing shoes was universal in urban homes, but rare in Checherta (where 64 percent of residents went barefoot). Combined with the village’s dirt floors, the practice seemed to increase the range of microorganisms people encountered.

“The remarkable changes in home microbial content across differing levels of urbanization raise the possibility that the reduced microbial exposure to environmental bacteria seen in modern homes contributes to immune and metabolic disorders, from asthma to obesity,” Dominguez-Bello said, adding that chronic illnesses are “the new disease paradigm in the industrialized world.”

That shift — chronic diseases more prevalent than infectious ones — is a noted phenomenon of development. But disease risk has also been linked to conditions of deprivation. The relative poverty of rural-dwellers (who live without shoes or walls) appear here to be associated with protective effects, suggesting the connection between urban life, relative wealth and disease risk might be complex.

The NYU research team agrees more work is needed. Dominguez-Bello noted, “Our pilot study was small in size and limited to one geographical region, so larger studies are needed before we can generalize these patterns.”

“We don’t have a complete picture of the microbiome,” University of Oklahoma biological anthropologist Christina Warinner explained in a recent public lecture announcement. “We cannot make targeted or informed [health] interventions until we know that.”

Until researchers achieve that goal, urbanites might want to reduce their chronic disease risk and increase their microbiome diversity an old-fashioned way: with a kiss.

The “Health Horizons: Innovation and the Informal Economy” column is made possible with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation.

M. Sophia Newman is a freelance writer and an editor with a substantial background in global health and health research. She wrote Next City's Health Horizons column from 2015 to 2016 and has reported from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Kenya, Ghana, South Africa, and the United States on a wide range of topics. See more at msophianewman.com.

Follow M. Sophia .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)

_on_a_Sunday_600_350_80_s_c1.jpeg)