Earlier this week, the Efficient Passenger Project launched a guerilla campaign to help subway riders in New York: Without asking permission, the EPP marked platforms to indicate the best places to stand for making certain transfers. New York’s subway platforms are very long — 500 or 600 feet — and getting off a train at the wrong place can mean missing your transfer and having to wait another 5-10 minutes, or even more at night. A little more than half of all New York subway trips involve transfers.

The reaction from the MTA was predictable. The agency told WNYC that the signs would come down:

MTA spokesman Kevin Ortiz confirmed that the transit agency was, indeed, planning on removing them. “These signs have the potential to cause crowding conditions in certain platform areas and will create uneven loading in that some train cars will be overcrowded while others will be under-utilized.” Besides, he said, “regular customers already know which car they want to get into.”

Surprisingly, many New Yorkers agreed with the MTA that willfully depriving riders of information would improve their experience. Most publications that wrote about the signs seemed decidedly mixed on the idea, and many commentators seemed to cherish their slight edge over fellow commuters.

Credit: WMATA

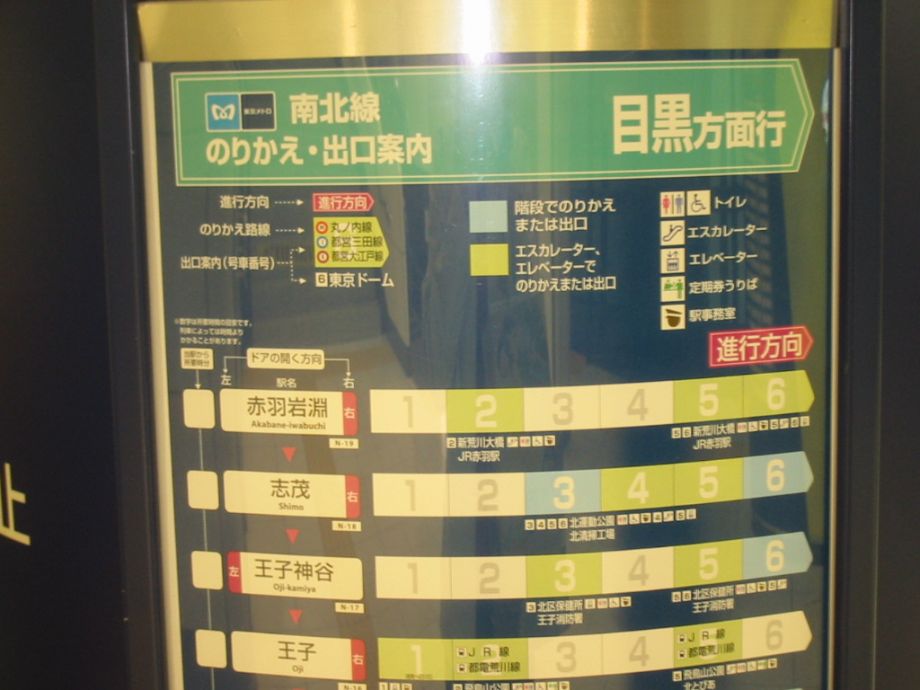

Elsewhere, posting clear transfer information is a tried and true idea. It’s standard practice in Tokyo, where transfers at key stations are marked on the platform itself, in addition elaborate diagrams on the wall showing the best places to stand. Such markings also exist on platforms in Seoul, and I wouldn’t be surprised to see it in other cities as well.

The theory is simple: Station access time counts. Railroads are expensive propositions, and planners will spend millions of dollars to save a minute here or 20 seconds there when designing them. One of the cheapest ways to shave off those minutes is to make stations highly accessible. That means ample and wide entrances and exits, clearly marked signs, and stations that are as shallow as possible. Saving someone 20 seconds walking to the end of the platform is like upgrading a stretch of track to allow for slightly higher speeds. In fact it’s even better, since walking through a station takes a lot more effort than sitting on a train.

So the MTA’s claim that posting this information would cause crowding is questionable, especially since the agency has never experimented with signs like these before.

For one, in many cases there would be no threat of crowding at all. The J, M and Z trains are notoriously roomy, so who cares if everyone crowds toward the back of the M from Brooklyn to better position themselves for a transfer to the 6 at Broadway-Lafayette? Anyone who’s ever made a transfer at an unfamiliar stations knows the feeling of stepping out of the subway car amid a crush of people, only to have to stop and look around for signs while people bump into you.

Credit: WMATA

In addition, not everyone transfers to the same place. Tokyo’s wall diagram illustrates this quite well: Each of the six cars is well positioned for at least one transfer. In New York, transfers are spread widely throughout the system. Someone coming from Brooklyn on the Q train could change to the 6 at Canal Street (stand about two-thirds of the way down the platform from the front of the train) or they could switch to the L at 14th Street (last car). Even then, most people traveling on any given train aren’t making any transfer at all.

The MTA’s sudden interest in platform crowding also seems insincere, given that for decades it has neglected other station upgrades that would spread crowds more evenly throughout trains, in addition to giving passengers easier access to stations. The L stops at First and Third avenues in Manhattan are the best examples — unlike some far less busy L stations in Brooklyn, they have exits only on the far western edges of the platform, so people crowd toward the fronts of trains when they get on in Brooklyn. (Coincidentally, EPP chose the L train for its initial roll-out.)

Given how crowded the L train is, you’d think the MTA would have gotten around to punching more staircases into the stations, especially since an exit at Avenue A from the First Avenue stop is the equivalent of bringing the subway one long avenue closer to transit-starved Alphabet City. But while the MTA has studied a pair of Avenue A entrances before, it has taken no action on building new staircases into the station.

It would be a small thing, but placing signs to make transfers more efficient would mark a decent step toward making New York’s labyrinthine subway more navigable. After the hubbub dies down and enough time passes so that it can plausibly deny any pressure from the EPP, the MTA should quietly roll out the signs itself.

The Works is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Stephen J. Smith is a reporter based in New York. He has written about transportation, infrastructure and real estate for a variety of publications including New York Yimby, where he is currently an editor, Next City, City Lab and the New York Observer.