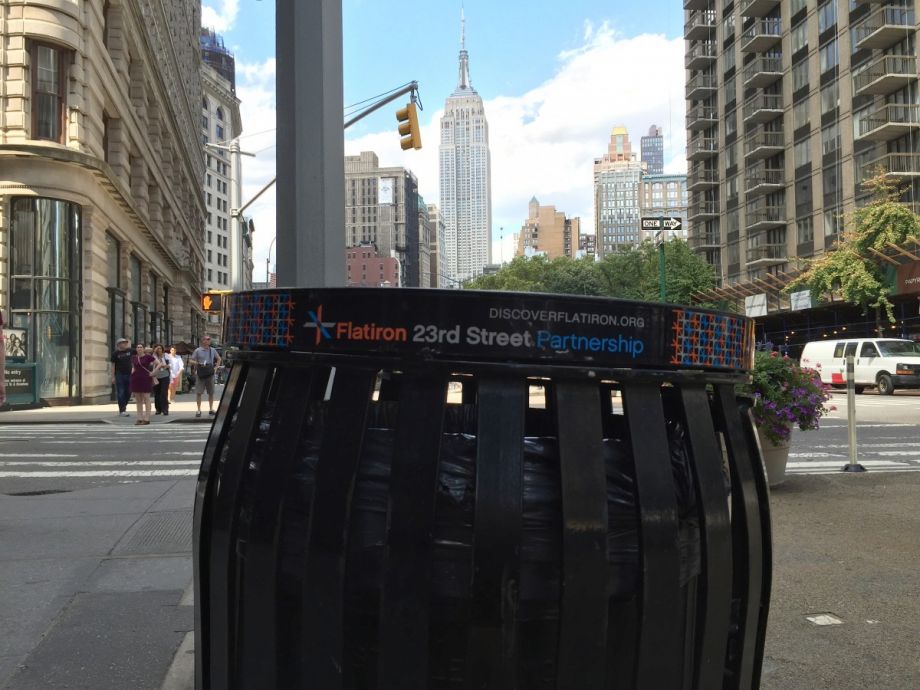

You see the names at every street corner. They’re usually on the trashcans. In New York, there’s the Times Square Alliance. Baltimore has the Downtown Partnership. There’s the Golden Triangle in Washington, D.C. Business improvement districts, or BIDs for short, are sort of like the urban equivalent to a mall: “Tenants” pay into a centralized organization that takes care of things like maintenance, safety, amenities and, of course, trash.

There are now over 1,000 BIDs in the U.S. alone, and New York counts 72, including 39 in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods. Walk up Broadway in Manhattan, and you’ll come across at least eight different BID trash cans, from the luxurious art-deco 34th Street Partnership receptacles to the Washington Heights BID-stamped trash bags. But the inequalities don’t end there.

Since their budgets are tied directly to property values, BIDs are all over the map financially. In New York City, they range from the Financial District’s $17.1 million Alliance for Downtown NY to the $49,740 180th Street BID in Queens, according to the FY2014 Annual BID Report from New York City’s Department of Small Business Services.

So when the New York City Council recently announced $1.25 million in supplemental funding for council members to support BIDs in their districts, it’s curious that each council member had the same funding cap — $24,000 to dole out. Jennifer Brown, executive director of the $2.2 million budget Flatiron-23rd Street Partnership, flat-out told Crain’s New York that they aren’t planning to pursue any of the supplemental funding for which they’re eligible.

Which begs the question, why not direct the supplemental BID funding to the 39 BIDs in low- to moderate-income neighborhoods? But, more broadly, how effective are BIDs at supporting entrepreneurs from low-income communities?

As usual when it comes to whether a broadly supported policy helps those who are most disadvantaged, data are hard to find. But a 2007 NYU Furman Center briefing did note that large, wealthy BIDs in New York City do have a significant impact on commercial property values and quality of life, while smaller BIDS had a negligible impact. The study speculates that perhaps there is a certain minimum level of resources below which BIDs do not deliver a net-positive impact on their catchment area.

That said, as more resources go toward BIDs, what is it that might be useful to position them as positive forces for communities, particularly low- to moderate-income communities?

“BIDs, done right, can do a lot,” says Michael Hendrix, director for emerging issues and research at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, a sort of think tank housed inside perhaps the country’s most prominent business organization.

Success, according to Hendrix, starts with tapping into the existing momentum of a community.

“Picking up on what was already happening and asking how to support that — that helps a lot, to the point where business development starts to happen naturally, and entrepreneurs don’t even realize why they end up where they end up in cities,” says Hendrix. He has has spent the last year or so traveling the country speaking with local leaders and entrepreneurs about what makes entrepreneurial ecosystems work. (You can dig deeper into his findings in the “Innovation That Matters” report, produced in partnership with D.C. tech incubator 1776.)

“When leaders of a city want to foster entrepreneurial ecosystems, sometimes they focus on place, as in let’s build new things, let’s just focus on amenities, let’s create these place-based expenditures, or they assume that by having enough smart people and enough capital that the rest will work itself out,” Hendrix adds. “Often what you find is that cities that have become successful at creating these ecosystems, they actually lack a good degree of capital or talent, but what is there, is highly networked and efficiently used within a cohesive, open, dynamic community. BIDs can contribute to that.”

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)