The investors eligible to use the new Opportunity Zones tax break are about as far-removed, demographically, as can be from the average Opportunity Zone resident.

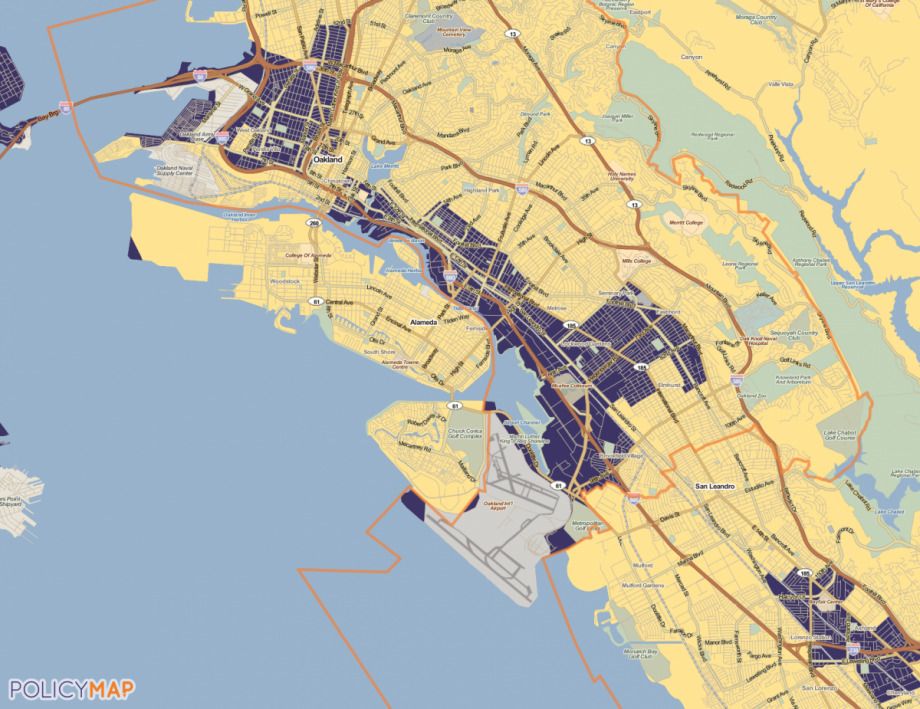

Some 35 million people live in the 8,700-plus census tracts that received Opportunity Zone designations in 2018. A majority of them are people of color. The selection process for Opportunity Zones was far from perfect, and some of those census tracts do already contain pockets of wealth or are already experiencing an influx of new investment, but on the whole, Opportunity Zone census tracts are definitely toward the bottom of the economic ladder.

On the investor side, Opportunity Zone tax breaks apply only to capital gains income — that’s income from selling off stocks, real estate, fine art or other assets that have appreciated in value since they were first acquired. The basic Opportunity Zones idea is you sell some appreciated assets, invest the income in eligible projects, and you get a capital gains income tax break for doing so. But in 2017, just 7.3 percent of tax returns reported any net capital gains income. Currently, white households hold an estimated 92 percent of the value of all stocks, 80 percent of the value of all real estate, and 83 percent of “other” assets. The wealthiest ten percent of households account for 64 percent of all assets in the United States. The average Opportunity Zone investor is likely to be someone who has stocks or other assets to sell — and that means, statistically, a wealthy white person.

Bridging the gaps between those two groups of people is no easy task, but for those who still hold out hope for any good to come of Opportunity Zones, it’s an important one. There’s nothing in the legislation that created the tax break requiring investors to invest in projects that are guaranteed to provide jobs for current Opportunity Zone residents. There are no requirements to finance housing that’s affordable for low- to moderate-income households. There are still no requirements to disclose any job creation, poverty alleviation or other social benefit data in conjunction with the use of Opportunity Zone tax breaks.

The lack of disclosure requirements and issues with campaign donors and political allies reportedly manipulating the final selection of Opportunity Zone census tracts to their financial benefit has Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) pushing legislation to repeal the tax break entirely.

Absent a repeal, some are pressing on with efforts to bridge the gap between current Opportunity Zone residents and potential Opportunity Zone investors, hoping to facilitate investment for projects that those residents actually want. At the East Bay Community Foundation, Sabrina Wu is spearheading an effort to bridge the community foundation’s wealthy donors on one side with community-based, grassroots organizations in their grantee portfolio on the other.

“We see our charge as mobilizing the various resources in the region to go to those projects and organizations that we feel are critical for our communities,” Wu says. “Opportunity Zones are really just one tool for that.”

Early next year, the community foundation plans to launch a Qualified Opportunity Zone (QOZ) fund — a vehicle for pooling capital and making investments in eligible Opportunity Zone projects and businesses. Most Opportunity Zone investment is expected to move through various QOZ funds, but most QOZ funds won’t be like this one. Wu and her team are working on a community governance model for ultimately deciding on which investments to make — taking a page out of the playbook from the foundation’s other recent work in community-led investing.

The community foundation already had a semi-formal network of estate planners, financial planners, attorneys, accountants and other professionals who manage money for the wealthy individuals and families who donate to the foundation. They come together every month for guest speakers and other programming about racial and environmental justice or socially responsible investing. Wu is expecting at least some of those professionals will be interested in having their clients take advantage of the Opportunity Zone tax break.

“We’ve had a number of conversations with those investment professionals just to gather their feedback on what they’re doing around Opportunity Zones, and learn a little bit more about what their clients are interested in, what kinds of returns are they looking for, what kinds of projects or deals they’re interested in supporting,” Wu says. “That’s all intel that we’re using to design our fund.”

While the exact details are still being worked out, the community governance model is already a key part of Wu’s pitch to the financial advisors and accountants who work for the East Bay Community Foundation’s donor base.

“That is the conversation we’ve been having with that side,” Wu says.

Wu’s also already meeting with local economic development professionals, asking around her grantees, and looking into potential projects that would meet the fund’s requirements.

“I started compiling a list of potential pipeline projects that could benefit from Opportunity Zone financing that meet the draft mission criteria that we have right now,” Wu says. “We’re focusing on projects that are led by developers or business owners and operators of color, who have a social mission, who are providing community benefits, or for housing developments where there are very strict provisions for affordability.”

The financial planners and investment advisors in the East Bay Community Foundation’s network are a subset of a much larger industry. There are now more than 12,500 investment advisor firms registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission — a record number, and it’s growing. Collectively managing more than $82 trillion, investment advisor firms play a key gatekeeper role to much of the nation’s wealth, and not just for Opportunity Zones.

Investment advisors come in a bewildering variety of sizes and specialties. Some specialize in certain sectors, or certain kinds of clients like doctors or lawyers, or mid-career black professionals. The industry also has some obvious but crucial shortcomings — investment firms led by women or people of color handle less than one percent of professionally managed assets.

But a growing number of investment advisors have clients whose goals go beyond merely making money. They want to avoid investments in fossil fuels or the private prison industry. They may also want to find investments in clean energy, or sweatshop-free labor conditions, environmentally responsible manufacturing or building. Some want to invest in affordable housing, or startups founded and led by women or people of color.

According to US SIF, a trade association for financial advisors with these kinds of clients, sustainable, responsible and impact investing assets now account for one out of every four dollars in assets under professional management in the United States.

Founded in 1985, Natural Investments is one such firm. It has clients with particularly careful tastes. Under the firm’s guidance, clients have invested in worker-owned cooperatives like Equal Exchange, community-controlled loan funds like the Boston Ujima Project, and steward-owned companies like Organically Grown Company. The financial returns aren’t exorbitant on any of these investments, but that’s not the point, according to James Frazier, a financial advisor with the firm.

“In the past it was harder to bring low-single-digit community investments to people,” Frazier says. “Now, with interest rates being so low, it’s not that big of a financial difference [to invest in a community-driven investment instead of some traditional, profit-seeking vehicles] and the consciousness around wealth inequality, historical disparities in educational opportunity, inherited wealth, the opportunity gaps, society’s becoming more conscious of these historical disparities and the need to address them. It’s all playing into and funneling towards this opportunity to move money and get it into these communities that fits right into the grassroots.”

So far, Frazier’s clients are so concerned about community buy-in on investments that he’s actually had trouble finding any Opportunity Zone funds, projects or businesses that his clients have taken an interest in. While some investment advisor firms have discretionary authority to pick investments on behalf of their clients, Frazier’s clients still have the final say. When it comes to Opportunity Zones, the answer so far has been no. The deals just haven’t felt right for the clients.

“I personally feel like very few people already had lots of relevant experience in real estate development who also were attuned to the community-centered intent of the legislation,” Frazier says. “So it’s just really been this gap where 95 percent-plus of everything that has come in has just been about making money and keeping the tax advantage for wealthy people.”

And yet, even with its clients’ pickiness, Natural Investment’s overall business has doubled in size over the past year, going from $500 million to $1.1 billion in assets under management. No Opportunity Zone tax breaks needed.

To Frazier, the East Bay Community Foundation’s QOZ fund with a community governance model would be right up his clients’ alley.

“More people are really seeking authenticity, they’re not just looking to see some firm slapping a new ‘impact’ label on it,” Frazier says. “People are coming to us from all over the place saying ‘I’m looking for this, but my current advisor just doesn’t have that experience or isn’t really committed personally to it.’ They’re looking for the deeper level of engagement for how we can actually help improve society.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)