“We’ve got to strengthen black institutions,” said Martin Luther King Jr., on April 3, 1968. “I call upon you to take your money out of the banks downtown and deposit your money in Tri-State Bank. We want a ‘bank-in’ movement in Memphis.”

It was part of a broad vision to go beyond boycotting white-owned institutions and start building up an economic base within the black community. King also mentioned six or seven black-owned insurance companies in Memphis alone, and encouraged listeners to buy policies at those. It was a call to action in what became known as his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. The next day, King was assassinated.

Forty-nine years later, a small band of volunteer organizers is helping to keep King’s proposal alive, launching Bank Black USA, an ongoing campaign to encourage anyone and everyone to move their money to black-owned banks, in solidarity with black communities that continue to experience structural discrimination and frustration with the broader economic and financial system. The campaign organizers first got connected with each other during last summer’s Bank Black campaign, spurred by a call to action from rapper and activist Killer Mike. They each have their own stories of frustration and disappointment with the financial system that motivate them to organize around the issue in their spare time.

Stephone M. Coward II was a senior at the University of Texas at Arlington when he joined his brothers in the historically black Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity to pool their collective assets and invest in each other. They created the Kappa Alpha Psi Federal Credit Union, continuing a long tradition of historically marginalized communities that have established credit unions when they felt like no one else believed in them enough to offer them access to capital.

“The reason why it’s important to me is, I do believe in creating generational wealth,” says Coward, who lives in Dallas. “A way for African-American families to have a strong platform where you don’t feel so beholden to those big companies who may not support things that matter to you.”

The all-volunteer, student- and alumni-run credit union didn’t survive the Great Recession years, and federal regulators closed it down in 2010. But the experience stuck with Coward, who now works in banking. “I got a glimpse of how to create something from the ground up,” he says. “I was fascinated by it.”

The demise of Kappa Alpha Psi’s credit union was not unique among black-owned financial institutions during and after the Great Recession. The downturn hit black family wealth the hardest. Lenders targeted subprime mortgages to blacks and Hispanics. When those mortgages failed, entire neighborhoods lost home values, and most black wealth was in housing rather than in other forms of wealth, according to a study by the ACLU.

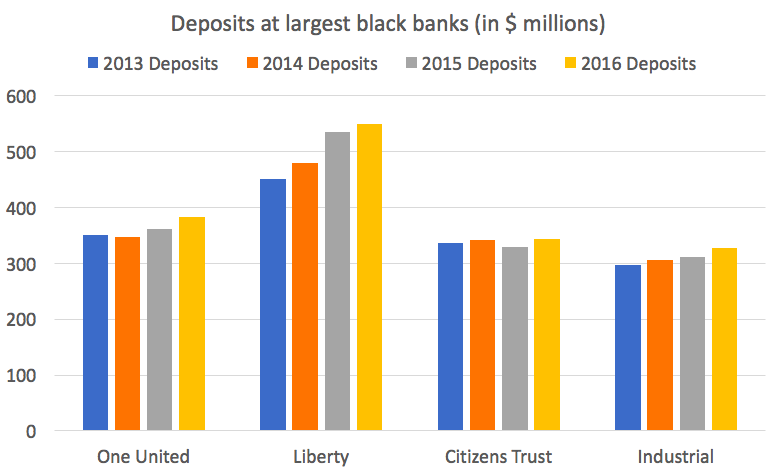

Even families that had conventional mortgages and made on-time payments every time still found their wealth depleted. Their banks, which held those mortgages, suffered too. There were 41 majority black-owned banks in 2007, but just 21 today, according to federal regulators. While some black-owned banks are reporting surges in new deposits as a result of last summer’s campaign, it’s not clear yet from federal data whether 2016 was a particularly high growth year for deposits at black-owned banks. The four largest black-owned banks, while they grew their deposit base in 2016 compared with 2015, did not appear to grow faster in 2016 compared with previous years.

Source: Reports of Condition and Income (Call), Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council

Are black-owned banks still necessary? Yes, says Justin Garrett Moore, another volunteer organizer behind Bank Black USA and executive director of the New York City Public Design Commission. (He’s also a Next City Vanguard.) Moore grew up in Indianapolis, in the historically black neighborhood of Mapleton-Fall Creek. His parents still live in the area, but the neighborhood is changing. The elementary school he attended, nearly all black when he was a student, was converted into a charter school and is now nearly all white students, he says. His middle school was also converted into a high school, serving a different population, over the objections of residents worried it would exclusively cater to wealthier and whiter populations, as reported in Chalkbeat.

Moore decided to do something: He co-founded a social enterprise, Urban Patch, which would acquire abandoned homes or vacant lots in the neighborhood and preserve them for the black community. They’d buy a house, rehab it, and rent it out at cost — taking no profit from each property, to keep it as affordable as possible for residents. It’s about keeping the neighborhood for its historic black residents, in a very incremental way, Moore says. They’ve rehabbed five houses so far.

But he’s encountered trouble getting loans to buy or rehab properties on the same blocks where he saw white families come in and get loans to rehab homes in similar condition. “Redlining still exists in America. They’ll tell you it doesn’t, but it does,” says Moore, referring to the historic practice of discriminating against people of color in the housing and financial markets. “I know that’s what your reason is [for denying a loan], you know that’s your reason, you won’t say it, but we all know what’s going on.”

In one case, Moore got so frustrated trying to get a loan from a bank, he maxed out a credit card just to buy a house. “I had a 20 percent down payment, 800 credit score, Ivy League degree, had everything that society says you’re supposed to have to do something like this,” he says, and still no one would extend him a loan. “My reading of that situation was, I am a black man in America, and I can’t buy a house in my own neighborhood.”

Last summer, inspired by Killer Mike, Moore compiled information on all remaining black-owned banks — checking account options, minimum deposit amounts, interest rates, Community Reinvestment Act ratings and more. Feedback from users helped and the data is now part of the Bank Black USA campaign.

Instead of promoting all 21 black-owned banks, the group whittled it down to four, as feedback from others convinced them a list of 21 was too daunting for the average person to mull over. They’re promoting the largest four black-owned banks by asset size — Boston’s OneUnited Bank (with locations in Miami and L.A.), Liberty Bank in New Orleans, Citizens Trust Bank in Atlanta, and Industrial Bank in D.C. They’re also the four banks that had the most positive feedback on user experience and ATM availability. The group has not received any funding from any of the banks they’re promoting, Moore says. (“No one’s asked, thankfully.”)

The group, which only meets virtually via email or GroupMe, will continue promoting the cause independently through their own networks, including professional networks, church networks, historically black college alumni networks, and historically black fraternities and sororities. They’re also inviting people to approach them with stories about individuals getting a loan from a black-owned bank after being denied elsewhere.

“It’s just letting people know the bigger angle is about individuals doing things that can contribute to equality, so black-owned businesses can go get a loan and not have to feel like your destiny is tied to somebody else’s stock,” Coward adds.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)