Imagine you’re an elected official in a city like Detroit, Philadelphia or Chicago — a place with so many vacant properties that one can only estimate, within two or three thousand, how many properties are not in productive use. Now, imagine someone hands you a sack of cash and instructs you to get as many properties as you can redeveloped, or at least make it so they aren’t serving as warrens of crime.

Do you focus on green space? Rehabbing empty homes? Demolitions? You only have so much money. Will you face political blowback if elected leaders see that you spend most of it in one part of town and not another? Redevelopment might not even be the ideal way to go. Sometimes neighborhoods with the strongest demand for space are best served when government steps in and saves a bit of land for everyone to use.

The problem of vacant land became acute during the housing crisis, when foreclosures skyrocketed and many homeowners simply walked away from their properties. Some of this land ended up in the hands of cities, and some in the hands of banks with no capacity or incentive to care for it. How can cities unload the properties they hold, and facilitate the transfer of empty properties held privately, to owners that can use them?

In the age of Big Data, these decisions are becoming less complicated. Last month, fellows with the University of Chicago’s Data Science for Social Good began working with the Chicago area’s newly born Cook County Land Bank Authority (CCLBA). The aim is to create a tool that will make it easier to process data on foreclosures, real estate trends and the like to determine which properties are the best candidates for redevelopment. Think of it as a data-backed triage unit for vacant land.

“I don’t think we’ll be able to create a model that makes those choices easy,” Thomas Plagge, a post-doc in astrophysics and mentor for the land use fellows said. “What I think that we’ll be able to prototype out is a selection of algorithms that the land bank staff can apply to different neighborhoods in different situations.”

The end goal is a customized tool for specific decision-makers, not a way for individuals to access government as with most of the products coming out of the civic tech movement. That said, if the tool works it could help cement consensus around decisions made by CCLBA staff, and may develop innovations that can apply elsewhere. The land bank model is spreading: New York has designated eight land banks now, with two more on the way. Discussions are underway to initiate them in the Pennsylvania cities of Reading, Erie, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Dauphin County, Pa. has already passed an ordinance, and, of course, the present trend toward land banks started in the county that is home to Flint, Mich.

An abandoned Cadillac in an abandoned Chicago lot. Credit: Flickr user John W. Iwanski

Cook County Commissioner Bridget Gainer began advocating for a land bank after the housing crisis left Greater Chicago grappling with a four-fold increase in foreclosures — they topped out at between 50,000 and 60,000 annually — yet with the exact same number of judges to move them through the system. This meant huge backups wherein it could take nearly two years to transfer title from the delinquent owner to the lender.

“So you’ve created a whole new class of victim: The people who live on the block with a vacant property,” Gainer said. “And no one is responsible before they get title.” The land bank’s role is to help these otherwise defenseless victims by using the levers of government to prod vacant properties into active use a little faster. “Its only purpose is to reduce the amount of vacant properties in Cook County,” Gainer said. “Whether that means renters, open space, flood mitigation, demolition — doesn’t matter. You’re just taking unproductive land and turning it over to productive use.”

Deciding on a use for each property is where the data tools come in. Take two neighborhoods in Southwest Chicago. Englewood has a population that’s a third of what it was in the 1940s. Brighton Park, meanwhile, showed robust growth throughout the 1990s. (While the growth has leveled off, you would still call the area “bustling.”)

Yet both neighborhoods have persistent problems with vacant properties. In Englewood problem properties won’t sell at any price, and the land bank would need to manage a decrease in housing supply. Whereas parcels in Brighton Park have potential for redevelopment, but someone needs to come in and clear up tangled titles and liens.

“A lot of times when the government intervenes in the real estate market, they have this kind of one-size-fits-all solution,” Plagge said. “We want to be more flexible, and we also want to be able to evaluate our interventions on the fly and bake that into the cake.”

Pragmatically speaking, at present the Cook County Land Bank Authority only exists on paper. It has a board and is about to begin a national search for an executive director. In August, the data fellows will submit their tool to the staff, which will begin a strategic evaluation of vacant parcels in the fall. The authority could begin acquiring and disposing of properties next year.

That is, if the authority gets funding from the state’s part of the National Foreclosure Settlement. New York State’s attorney general has already committed up to $20 million to the land bank programs there, so Cook County’s request is not unprecedented. Gainer said that CCLBA requested $20 million from the $70 million awarded to Illinois for use in acquiring vacant properties. The request is before state Attorney General Lisa Madigan now. *

Other cities will be watching. So far, New York State has designated eight of 10 land banks, including in cities like Syracuse, Buffalo and Rochester, authorized by an act signed into law by Gov. Andrew Cuomo in 2011. Applications for the last two spots are open now. Pennsylvania State Rep. John Taylor (R-Phil.) was able to move a law through to Gov. Tom Corbett authorizing land banks, modeled on the law passed in Michigan to enable Genesee County (home of Flint) to begin land banking.

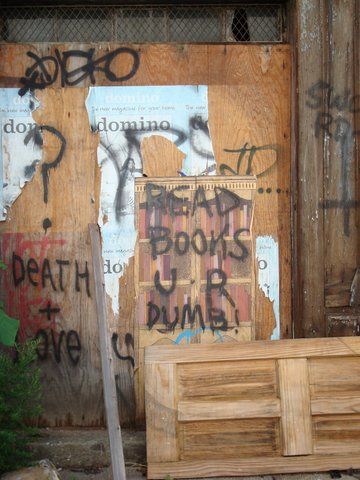

A vacant on North Broad Street in Philadelphia. Credit: Brady Dale

Now that land banks are permitted in the Keystone State, Philadelphia City Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez has proposed one for its largest city. It’s an urgent issue for local elected leaders, since voters are getting evicted over arrears while nonresident speculators are left alone. A standing coalition has achieved consensus on the land bank among groups that often don’t agree. On the public side, the mayor’s office has created a unified resource listing all city-owned properties. But these properties are still held by multiple agencies, each of which has different a timeline and process for turning them over.

City Council President Darrell Clarke has not yet scheduled a hearing on Quiñones-Sánchez’s legislation, and Mayor Michael Nutter hasn’t created any pressure by indicating which agency all city properties would move into if it passed. While explanations for the gridlock vary, one cause could be hesitancy on the part of council members to give up a special, off-the-books, quasi-veto power.

At present, Philadelphia city council members can choose to not move forward with a property transfer in their given district, letting the request sit for two years before it’s rejected with little transparency. In theory, this is because council members posses the street-level knowledge that technocrats in City Hall might lack. If passed, the land bank legislation would move all decisions about public land transfers into a committee. The Council would still dominate the process, but it would have to make a decision within a stated timeline and explain any rejection in writing to the applicant, a major shift from the way things are done now.

If this is indeed the issue, then a potential solution might lie the approach taken by the data fellows in Chicago. Voters may decide that that the council’s check against bureaucracy is no longer necessary should data transparency and comprehensibility improve as much as the Cook County fellows say it will.

As Gainer said, this is how sharing data — and making it comprehensible to multiple stakeholders — can help. “What I think gives communities power is a visual representation of the data,” she said. “If you go to people and say, ‘Here’s everything. We’re all looking at the same stuff,’ it enables the community participation in a really democratic process.”

In fact, there’s hope that Cook County’s data tool may go even further than inform people about market conditions. It may also model outcomes for neighborhoods over time, testing the various benefits if different strategies are deployed. For example, it could show what might happen to property values nearby if a set of parcels were turned into open space, as opposed to offering them for redevelopment or rehabbing the property for rental units.

As powerful as the tool sounds, no land bank will have enough money to acquire all the vacant land in a given municipality. Nor will any land bank be strong enough to resist the temptation of currying political favor in cities that give them authority. The data tool is another test of whether information openness will be enough to empower community members to hold politicians to the priority of getting land back into productive use.

This presumes that community members are motivated to hold their leaders accountable. But in a system where many citizens see vacant land as depressing their property values and putting their families in danger, this could well be one of the policy areas where data freedom, and clarity, is best suited to make a difference.

* Update: Madigan announced on Tuesday how the state will allocate National Foreclosure Settlement money. CCLBA will get $6 million (much less than the $20 million requested) to launch the land banks and help them generate additional public and private funds. Part of the $6 million will also go toward supporting the newly formed South Suburban Land Bank, which covers the suburbs to Chicago’s south and southwest.

Brady Dale is a writer and comedian based in Brooklyn. His reporting on technology appears regularly on Fortune and Technical.ly Brooklyn.