As director of the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative (EB PREC), Noni Session is building a movement of co-op residents, black and indigenous businesses and cultural organizations, general contractors, accountants — and also some like-minded investors.

“When I’m talking to people who may or may not invest in our work, our co-op’s highest interest is to build a supporter and a follower, not just someone who puts capital in our pot,” Session says.

Like most investor pitches, Session’s pitch begins with the big picture.

“We have a pretty hefty mission, which is to align the technical, the financial, the networks and the relationships necessary to support black and indigenous people of color and allied communities to collectively organize, acquire, finance, and asset manage land and housing in Oakland and the East Bay,” Session says.

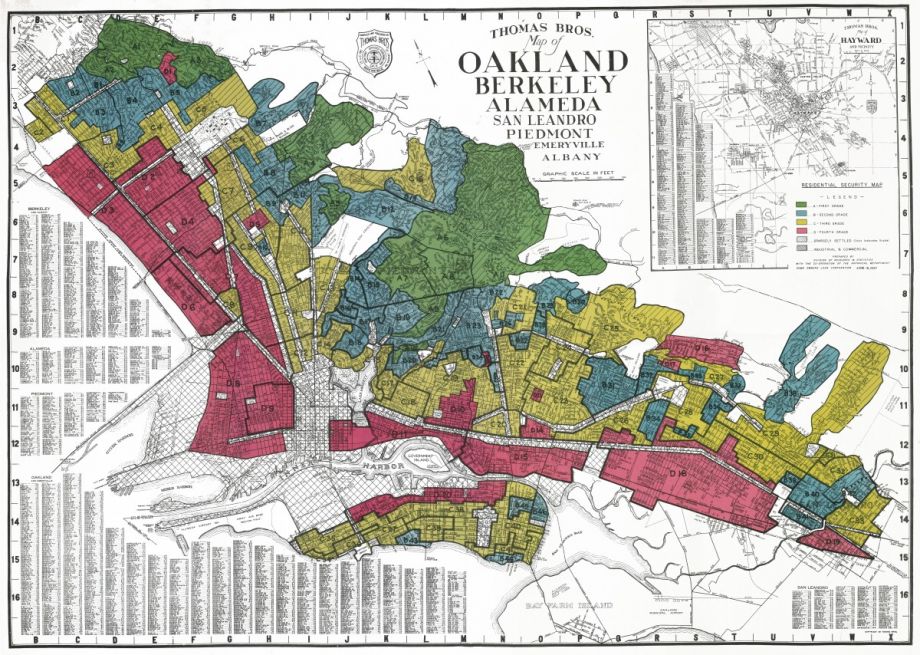

Then she dives into how personal the work is for her. Session’s grandparents first arrived in Oakland in the early 1940s, as part of the Great Migration. Her parents were small business owners, and Session remembers a time in her early childhood when she was surrounded by a tight-knit black community that did its best to support each other under politically-created and privately-perpetuated segregation. Starting in the early 1980s, she remembers, deindustrialization, the invasion of drugs and then mass incarceration began taking their toll on her community.

“I watched this city fall apart,” Session says. “I watched it suffer from the neglect we see in urban centers nationwide.”

After returning home from doing doctoral work in anthropology, Session found her city in a development boom, but none of the development was benefiting the community that raised her — in fact it was continuing to dismantle them, forcing many to live on the streets. So now she’s seeking out investors who will join a movement, “not only to slow gentrification but also to re-assemble these communities who have been systematically dismantled by the very tools we’re using to do this work — the financial system and financial tools,” Session says.

So far, the investor response has been positive. EB PREC’s first investment campaign, completed last month, raised $200,000 from over 160 investors who invested a minimum of $1,000 each for a term of at least five years. EB PREC offered to pay investors an annual dividend of 1.5 percent, but nearly half of the investors so far have actually declined to take a dividend. The funds will go to rehabilitate the first property acquired by EB PREC — a four-unit housing co-op in West Oakland.

“It’s really very simple, it’s just that people’s imaginations are super-compressed when it comes to the folks they call poor people,” Session says. “We do the same thing everyone else in this market does — we buy property and we pay back investors on time. The marked difference is a slightly lower interest rate which is less extractive, and we support people in pulling together an affordable capital stack and teaching them how to do long-term asset management.”

It took years of complex legal and organizing work to get to that sense of simplicity.

EB PREC isn’t a nonprofit (though it does have a nonprofit arm). It’s a cooperative incorporated under California state laws, which permit cooperatives in the state to raise capital from members without having to jump through the legal hoops that conventional businesses have to go through to raise capital directly from investors — so long as those investors are residents of California. (Illinois recently created a similar pathway to raise capital under its cooperative law, modeled directly after California’s.)

EB PREC benefits from a change in California’s law, which took effect in 2016, that upped the maximum amount of investment a cooperative can raise from each member, from $300 to $1,000.

The initial idea came from the mind of securities attorney Janelle Orsi, co-founder of the Oakland-based Sustainable Economies Law Center, which helped push through the 2016 change to California’s cooperative law.

Orsi says California’s existing laws and regulations around condominiums, housing cooperatives, and nonprofit entities were raising challenges for the Law Center’s work in support of housing or other community development projects with some kind of shared-ownership dimension. It had become prohibitive for low- and moderate-income households to cobble together the financing for their own affordable condominium or cooperative housing in California. At the same time, Orsi says, nonprofit entities have challenges raising capital, particularly if some of the investors are also beneficiaries of the nonprofit.

So in January 2016, on a long ride to visit family in Los Angeles, Orsi sketched out the rough idea for a new kind of entity enabled by California’s cooperative law. The new entity would take property out of the speculative market and into shared ownership, combining resident owners and non-resident owners of multiple properties in one portfolio — an entity Orsi dubbed, “a permanent real estate cooperative.”

Then, in February 2016, a member of the People of Color Sustainable Housing Network walked into the Law Center’s “legal café” — basically open office hours that the Law Center hosts three times a month outside its offices. Starting out as a meetup group in 2015, the People of Color Sustainable Housing Network grew quickly to more than a thousand members. After the meeting, Orsi sent the group the rough sketch she had just wrote of a permanent real estate cooperative, and the light bulbs went off almost instantly. The Law Center started meeting regularly with the network to discuss initial details, and the two organizations incorporated EB PREC in 2017.

In some ways a permanent real estate cooperative is like a conventional real estate business. In other ways it’s radically different.

“It buys land, it develops it, renovating or building on it, or just buys the property,” Orsi says. “It has a staff that has honed its expertise in a lot of aspects of real estate development. It earns money in a sense by serving as a landlord. But what happens with that money and how that money is calculated is very different from a conventional real estate developer.”

Those key differences are spelled out in the organization’s bylaws, drafted over the course of more than a year of discussions between the Law Center and the core group from People of Color Sustainable Housing Network that eventually became EB PREC’s current staff. Those discussions intensified in the second half of 2018.

“It was the most participatory legal document I’ve ever created, as far as people giving meaningful input that actually shaped the document as we went,” Orsi says. “I have never had so much fun in meetings. Every other week we’d have these two-hour meetings and it was always like what are people going to suggest now? Because lawyers think they know everything, we think we know how to write legal documents but then you put five non-lawyers together to write the document, and the stuff they would come up with we were like, ‘wow.’”

The final document is accented with Orsi’s signature cartoons, which she’s known for using often in presentations as well as legal documents to make complicated legal and financial concepts more accessible.

“Janelle loves slides so we do a lot of our work in slides,” Session says. “We’d give feedback … Then she’d come away and polish those and then we’d come back and go to the next article. It was arduous, [but] the cross fertilization has been amazing.”

EB PREC’s bylaws recognize four classes of owners: resident owners, which include people who live in the cooperative’s portfolio properties as well as businesses who may be operating on those properties; investor owners; staff owners; and community owners — dues-paying members who volunteer their time in different ways to support the cooperative’s organizing efforts. The document also spells out the process for selecting the cooperative’s eight board members — five elected by members, three appointed by key outside allies, to “anchor EB PREC to its mission and to ensure representation of black, indigenous and people of color communities on the board.”

EB PREC’s bylaws also feature a number of provisions designed to ensure that the needs of investors never take precedence over the mission of the cooperative to provide permanently stable, affordable housing and space for commercial or cultural use. Investor shares are non-transferable, so they can’t be sold to another individual or institution. There’s the 1.5 percent annual dividend, which the cooperative can defer payment of in any given year. If an investor needs to leave the cooperative and cash out, the cooperative has up to five years to buy back their share and pay any dividends owed. If EB PREC fails and must sell off its assets, residents get right of first refusal to acquire the cooperative’s properties, and if someone else ends up acquiring those properties, residents get refunded any equity they’ve paid into the cooperative before investors get their share.

So far, the cooperative has found investors who are more than happy to invest on those terms. Some have already invested twice — after their initial $1,000 ownership share, a select few with the means to do so provided additional capital through a private offering, filling in the last $40,000 or so that EB PREC was looking to raise through its first campaign.

“Most of our investors come from activist communities,” Session says. “Some are white allies, many are [people of color] allies who have a constant awareness that nothing has been moving in the direction of community control. Then there’s this other body of folks working in the nonprofit field who are really fatigued with the way that the nonprofit field works.”

Some investors have come in on a pledged basis, paying off their $1,000 share over five years. “Those are the ones that are most impactful, folks who come in and say ‘I really have to look at my finances but I really believe in this, how can I invest,’” Session says.

For now, the Law Center and EB PREC staff continue to raise grant funding to support the cooperative’s staffing. Eventually, once the cooperative’s portfolio becomes large enough, it plans to pay for its own operations — and the bylaws spell out living wage requirements as well as salary maximums based on Oakland-area income levels. Each property in the portfolio is intended to be self-sustaining on its own, and the bylaws spell out how the surplus from any property contributes to EB PREC staff salaries, rent rebates for residents, and investor dividends.

In some ways EB PREC resembles the savings-and-loan associations of yesteryear, where neighbors invested into a communal pot of money that they took turns borrowing from in order to support each other’s acquisition of property. One big difference here is that this vehicle has room for investors who don’t live or work on the cooperative’s properties — though they may eventually shop at the businesses in those properties or support the cultural organizations working there. Prospective projects in EB PREC’s pipeline include healthy food and other retail as well as cultural spaces, in addition to housing.

EB PREC’s vision is also something much larger than homeownership for one family at a time, and larger than just one community or one city. The cooperative sees its work as an attempt to demystify the entire process of real estate — securing properties for acquisition, assembling capital stacks, and managing properties for the long-term — so that community organizers everywhere, of every marginalized group, can bring in communities to participate as an active player in their own development instead of just being passive recipients or victims of displacement.

“As we develop the strategies, techniques, the networks, the resources, the background knowledge that’s often withheld from folks, we’re going to put all that out there as open source material so it can scale not only in our city but it can scale to others,” Session says. “We have a political, philosophical take on what kind of shifts need to be made and those are the things that really fire up and empower people even when their social setting may be much different from ours.”

This article is part of The Bottom Line, a series exploring scalable solutions for problems related to affordability, inclusive economic growth and access to capital. Click here to subscribe to our Bottom Line newsletter.

Oscar is Next City's senior economic justice correspondent. He previously served as Next City’s editor from 2018-2019, and was a Next City Equitable Cities Fellow from 2015-2016. Since 2011, Oscar has covered community development finance, community banking, impact investing, economic development, housing and more for media outlets such as Shelterforce, B Magazine, Impact Alpha and Fast Company.

Follow Oscar .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)