Suzanne Schulz isn’t trying to cast any shade, but from her perch, the news out of Minneapolis, where the city council recently voted for a comprehensive plan that recommends ending exclusive single-family zoning, isn’t quite so groundbreaking as everyone seems to think it is.

Schulz is the managing director of design, development & community engagement for Grand Rapids, the second-biggest city in Michigan. And when it comes to permitting more units in areas traditionally zoned for single-family living, she says, “We’ve kind of been doing this for a decade.”

Earlier this month, Minneapolis approved a comprehensive plan that recommends allowing at least three units in all properties that are currently permitted just one. Similar changes are being considered in Seattle, as Next City has reported, and in the state of Oregon. Proponents say allowing single-family neighborhoods to add more units without drastically altering the scale of the built environment can help increase the supply of low-cost housing and chip away at residential segregation patterns that were, in many cases, an explicit goal of single-family zoning in the first place.

Ten years ago, when Grand Rapids set out to rewrite its zoning ordinance, the common complaint from developers as well as residents was that it was unpredictable, Schulz says. The ordinance had been amended more than 300 times since it was adopted in 1969. The city had earlier created a master plan in 2000 based on “smart growth” principles, Schulz says, encouraging a mix of housing types at various price points.

To rewrite the ordinance a decade ago, Schulz says staff met with neighborhood associations to hear what they wanted the code to promote. As a precursor to the rewrite, Schulz helped develop a “Neighborhood Pattern Work Book,” which identifies Grand Rapids neighborhoods by the era in which they were primarily developed: Turn of the century, early 20th century, post-World War II, and late 20th century.

“Preserving neighborhood character was important,” Schulz says. “But how do you quantify or codify neighborhood character?”

What they ended up with is a type of zoning that Schulz refers to as “form-based lite.” Residential districts are either low-density or mixed-density, and most housing types are permitted either by right or by a special exception, which requires a public hearing before the planning commission. But the special exception process takes just five weeks, and the planning commission approves 97 percent of applications, Schulz says. The public hearing process allows residents an important opportunity to weigh in, Schulz says, but keeps the responsibility for administering land use in accordance with the master plan in the planning commission’s hands.

“Neighbors still have an opportunity to provide input,” she says. “We do leave space for some of those conversations, but we’re also clear that we do expect to see a range of different housing types and densities in our community.”

Putting form rather than use at the center of the zoning process can help mitigate the most exclusive aspects of traditional single-family zoning, says Marta Goldsmith, director of the Form-Based Codes Institute at Smart Growth America. The theory is that enacting clear standards and making the approval process easy will allow developers to build out land according to zoning as simply as possible, and keep regulations from constraining housing supply unnecessarily.

“I think that form-based codes can create opportunities to build additional units while maintaining the character of the neighborhood,” Goldsmith says. “They can do it by slightly increasing heights or densities while maintaining the form of single-family neighborhoods … They can also expedite the permitting process by having transparent building standards, while allowing existing densities to be fully optimized.”

Schulz says that when it came time for the Grand Rapids City Commission to approve the rewritten zoning ordinance a decade ago, not a single resident came out to oppose the law. She gives credit (somewhat improbably) to “A very smart citizenry,” but also luck, and a lot of community engagement.

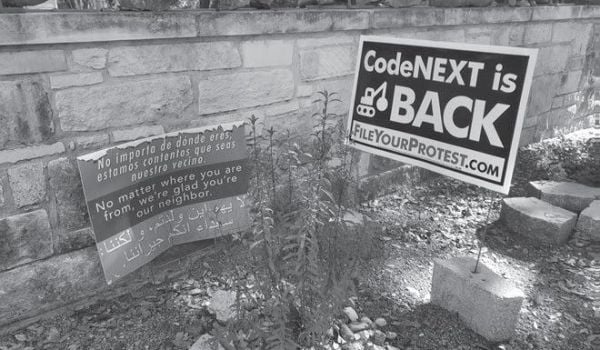

Still, while the zoning ordinance may have made building easier, it hasn’t saved Grand Rapids from the same affordable-housing challenges that other cities are facing. No matter how a city handles zoning, the cost of construction and availability of land and labor can be obstacles to expanding the supply of low-cost housing, Schulz says. And the city’s more administrative zoning approach hasn’t brought an end to controversies around housing and land use. Over the last year, the city has considered a range of proposals aimed at making building even easier, with some residents vocally opposed to changes they saw as being aimed at removing them from the process. But, Schulz says, she sometimes hears from elected officials who are glad that they aren’t often involved in zoning decisions at the project-by-project level.

“There’s some distance between the planning commission and elected officials,” Schulz says. “Not all constituents may like that, but you have a body that’s charged with administering a master plan.”

Jared Brey is Next City's housing correspondent, based in Philadelphia. He is a former staff writer at Philadelphia magazine and PlanPhilly, and his work has appeared in Columbia Journalism Review, Landscape Architecture Magazine, U.S. News & World Report, Philadelphia Weekly, and other publications.

Follow Jared .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address)