As you travel the 200 miles north from Albuquerque, N.M. to the Colorado border, there are exactly five places to use a bathroom if you like indoor plumbing. A crossroads makes a town, and a city is anywhere with more than one school.

The first city on the Colorado side, Durango, has 17,000 residents and 14 public schools. Just five years ago, the city had only 11 schools to serve the same student population. This spring, a 4-year-old charter school, Animas High, graduated its first class of seniors, while the new charter Mountain Middle School finished its second year. Big Picture Learning High School, a district initiative, graduated its second class.

The increase in schools in Durango is driven in a large part by the educational aspirations of the in-migrating creative class, not by an increase in schoolkids. Yet as successful professionals move to the mountains from the coastal cities, in a large part to give their children an idyllic setting for their youth, are they remaking the small valley culture in the image of the urbanized coastal cities they left behind?

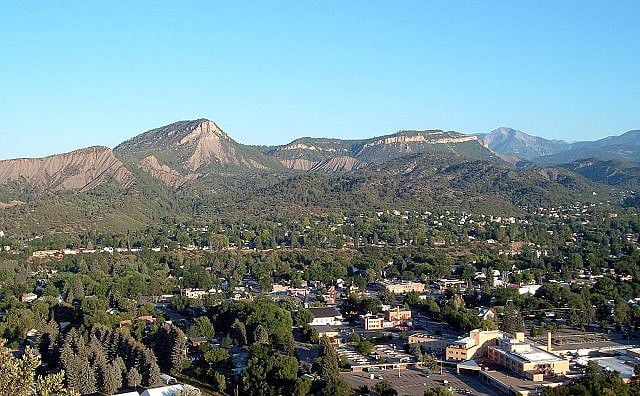

From the mesa above its valley, Durango’s Animas River looks like a silver necklace strung with beads of homes and shops. With 52,000 regional residents, the area’s mean income has leapt from $43,000 to $70,000 in the past decade. Durango was the number-one “micropolitan” area for economic strength in 2011 (slipping to 13 this year), according to Policomm’s analysis of Office of Management and Budget figures. (Micropolitan statistical areas have populations between 10,000 and 50,000 and a central city.)

Durango, like Helena, Mont. and Juneau, Alaska, is a small western town swelling with “creative class” workers, who have joined the tourist service industry workers in what some residents describe as paradise. With the influx of those in business, management, science and arts — who represent, according to the census, 40 percent or more of the populations in these towns — comes new expectations of what school should do for a child.

The schools in Durango 9-R (the district name) are relatively strong, with test scores and graduation rates at or slightly above Colorado averages. But five years ago, there was just one high school, which left some parents feeling constrained.

“We are a small town but people say we are a special place, with every weekend a fundraiser or festival celebrating what we have in southwest Colorado,” says Jesse Hutt, a pediatrician and parent who moved to Durango 17 years ago from Florida. “A new generation of people was moving in and saying that the status quo won’t cut it.”

Hutt, along with five other parents, transplants from the East and West coasts, met for months to discuss their idea of great education and research models, before eventually applying to the state Charter School Institute for a college preparatory high school whose curriculum revolves around project-based learning.

This year, the first class of 49 graduating seniors at Animas High School were all accepted to college (except one student who chose not to apply), with many headed to the local Fort Lewis College or University of Colorado and others flying out to Brown and Stanford. By comparison, Durango High School has 1,100 students and a 77 percent graduation rate, with two-thirds of graduates going on to college. While approximately 11 percent of Durango High School students are low-income based on free or reduced lunch qualification, Animas High School does not even keep track, since it does not have a lunch program.

In Colorado, home of legal pot and birthplace of the Libertarian Party, choice is a verb. With open school enrollment across the state, students can “choice” into and out of a school or district, and charter schools now account for 11 percent of the total schoolkid population. Funding for Durango’s charters comes from the state, not the district, which previously ran two charters that closed (in Colorado, local districts authorize charters unless they lose this power, as Durango 9R did). The money follows the student. But state data shows that the net loss of students “choicing” out of Durango 9R, which covers 1,000 square miles, is small, at 21 of approximately 4,700 total students.

“Choice is a big initiative here in the region,” says Julie Snider-Popp, communications and marketing director for Durango 9-R, which also has a new superintendent, a former charter school administrator named Daniel Snowberger. In response to the demand for choice four years ago, the large district high school broke itself up into smaller learning communities, one of which, Big Picture, became a separate school unto itself, for students who were not thriving in the traditional setting.

Big Picture, which operates schools around the country catering to students who don’t thrive in large traditional high schools, offers hands-on learning, which sounds a lot like vocational. The development of Animas High School, says Nancy Heleno, board president of Mountain Middle School and a native New Jerseyan, “was really propelled by a handful people who wanted better for education” and had relocated to Durango from the coasts. “The idea that resonated here was the ability to think critically,” says Heleno, who researches and writes about child psychology as well. (This writer is not so different, as an urban New Jersey resident who has “choice” by being able to move to a nearby suburb, pay for private school or, in my family’s case, lottery into a progressive charter school.)

Children at Mountain and Animas design elaborate portfolios and projects, which they post online, alongside those of their teachers. Since Animas and Mountain opened, parents from Telluride and Pagosa have moved for the new schools, while one New Jersey mother flew out several times to make sure her child had a place at Mountain next year. Colorado will pay for them all.

These leads some critics of charter schools to point out that these state funds might have instead gone to students with no other options than their district public — and, in fact, Durango already had a pretty decent local option. But in Colorado, district and charter schools seem to be making nice. Gov. John Hickenlooper recently signed a new school finance law that allows for new taxes to raise money for schools, specifically for at-risk students and more early childhood education. The Colorado League of Charter Schools initially opposed but ultimately supported the bill, which now requires a referendum in November to decide how to fund it. Snider-Popp, for one, is sanguine that the Durango model represents choice among many decent options. “Everyone has different learning styles and needs,” she says. “The ultimate goal is to serve all learners.”

The national debate over funding for charter and district schools has mainly centered on the former as vehicles for school choice in big, high-poverty cities, where district schools have not yet been able to make most children of poverty college-ready and where the poorest families were never able to move to the suburbs. In the Mountain West, charter schools often attract the children of well-educated “creative class” workers. The new migrants can bring their computer-based work with them and often can move where they want, which is increasingly a semi-isolated, semi-rural micropolitan area.

To college-educated professionals, choice is not a new trend but an assumption. Options among schools, like jobs and residences, are consciously debated and then selected, not taken as a given, in a large part because of the solid educations and backgrounds those professionals were born to or found themselves. The idea that education is more than learning how to read, write and do basic math is particularly appealing to new coastal migrants who assume these skills, as well as the English language, as a birthright.

While Animas High School celebrates its first graduating class and its accomplishments, Mountain Middle School is still finding its footing, two years in, with test scores just average and initial promise of personalized project-based learning colliding with real-life challenges and tweens. Some families are “choicing” back to the district or a local private school.

Carly Berwick writes about education and culture for Next City, as well as The New York Times, ARTnews, and other publications.

_(1)_600_350_80_s_c1.JPG)